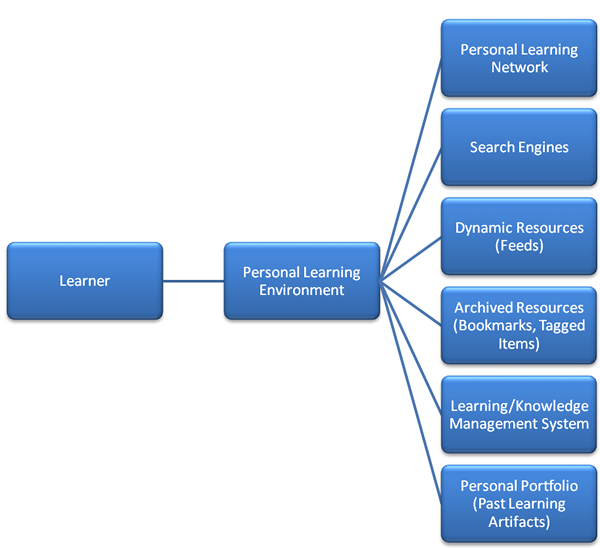

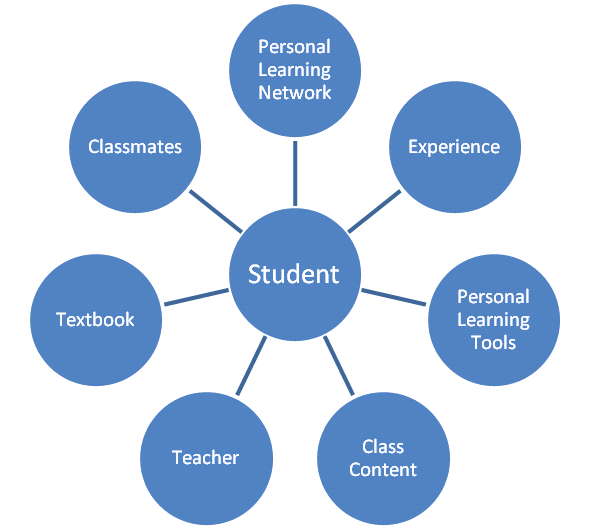

Figure 1: Visualization of a web-based Personal Learning Environment

Jessica McElvaney

Zane Berge

Authors

Jessica McElvaney is a graduate student in the Instructional Systems Development Program at the University of Maryland (UMBC).

Zane Berge is Professor and former Director of the Training Systems Graduate Program at UMBC. Correspondence regarding this article can be sent to: berge@umbc.edu

Abstract: This paper explores how personal web technologies (PWTs) can be used by learners and the relationship between PWTs and connectivist learning principles. Descriptions and applications of several technologies including social bookmarking tools, personal publishing platforms, and aggregators are also included. With these tools, individuals can create and manage personal learning environments (PLEs) and personal learning networks (PLNs), which have the potential to become powerful resources for academic, professional, and personal development.

Résumé : Cet article explore les diverses façons dont les technologies Web personnelles peuvent être utilisées par les apprenants, ainsi que la relation entre ces technologies et les principes d’apprentissage connectivistes. Y sont également présentées les descriptions et les applications de plusieurs technologies, y compris les outils sociaux de mise en signet, les plateformes de publication personnelles et les agrégateurs. Ainsi outillées, les personnes peuvent créer et gérer des environnements d’apprentissage personnels (EAP) et des réseaux d’apprentissage personnels (RAP) qui recèlent le potentiel de devenir de puissantes ressources de perfectionnement sur les plans universitaire, professionnel et personnel.

The ability to personalize one's online experience is not new, each Internet user creates their own personal web by deciding which sites to visit, which blogs to read, which news sites to trust, and which to ignore. However, in recent years a growing number of free technologies have become available that have made personalization possible on a grander scale. Free and easy-to-use technologies offer new ways to find, organize, create, and interact with information. These personalized internet applications that are already used by many for socializing and entertainment also show great promise for education and training.

The 2009 Horizon Report defines personal webs as "customized, personal web-based environments . . . that explicitly support one's social, professional, [and] learning . . . activities via highly personalized windows to the networked world" (Johnson, Levine & Smith, 2009, p. 19), and heralds them as an emerging learning trend. This paper explores personal web technologies (PWTs) and their learning applications. Examples are given of commonly used, customizable technologies such as: social bookmarking, personal publishing tools, aggregators, and metagators. Additionally, this paper investigates how PWTs can strengthen connections between academic and workplace learning by creating a continuous, dynamic learning environment for individuals as they move from one role to the next (Cohn & Hibbitts, 2004). Finally, several challenges to using PWTs will be outlined.

In today’s world, learning needs extend far beyond the culmination of a training session or degree program. Working adults must continually update their skills and behaviours to conform to the constantly changing demands of the workplace (Lewis & Romiszowski, 1996). In times of rapid change, it is not always prudent or possible to offer formal training for each individual’s every need, and some needs may best be addressed by the individual him/herself. Using freely available personal web technologies, employees can create a personal learning environment (PLE) to manage their own learning resources; whether these are wikis, news feeds, podcasts, or people. When individuals encounter a knowledge gap, they can use their PLE to search for information immediately. Utecht (2008) also comments on the usefulness of personal learning networks (a community of colleagues, peers, teachers, and other individuals that the learner has assembled and can connect to using PWTs), "you cannot know it all ... [but] you can rely on your network to learn and store knowledge for you” (Stage 5 section, para. 1, line 2).

The use of PWTs for learning directly supports several principles of connectivism, a learning theory outlined by Siemens (2006): (i) Knowledge rests in networks, (ii) Knowledge may reside in non-human appliances, and learning is enabled / facilitated by technology, and (iii) Currency (accurate, up-to-date knowledge) is the intent of all connectivist learning activities (p. 31).

In a sense, PWTs allow learners to expand their capacity for knowledge by connecting to external resources (other people, online databases, reference sites, etc.). If individuals can sufficiently develop their ability to find, organize, and manage these connections, their available knowledge does not have to be limited by the confines of their own skulls.

Figure 1: Visualization of a web-based Personal Learning Environment

Using today's digital tools, anyone with an internet connection can easily publish their thoughts to a global community via blogs, discussion forums, streaming videos and other media which leads to the rise of new voices and sources of information. Still, with these new resources, come new challenges. Coates (2009) warns that "we find ourselves awash in petabytes of information of widely varying quality" (para. 1, line 5). How can this flood of information be managed and used to the learner’s advantage?

To navigate the Internet more efficiently, individuals can assemble a virtual toolbox from an ever-growing list of free, and often open-source, technologies to aid in aggregating, organizing, and publishing information online. When personal web technologies are used for educational or training purposes, they offer learners the flexibility to choose from a variety of tools and methods to accomplish their goals. Each individual has the opportunity to choose how they manage online resources according to their own preferences. For example, to conduct online research, one learner may broadcast their topic to friends and colleagues via a social networking site and receive a list of suggested sources, while a second learner may subscribe to several related blog feeds, while a third combs through a list of tagged items on a social bookmarking site. Eventually, all three learners may arrive at a similar set of sources, despite their differing paths.

To create a personal web for learning, it is first necessary to explore what personal web technologies are, where to find them, and how to use them. Several major categories of personal web technologies that exist are summarized in the next section: social bookmarking and research tools, personal publishing tools, and aggregators.

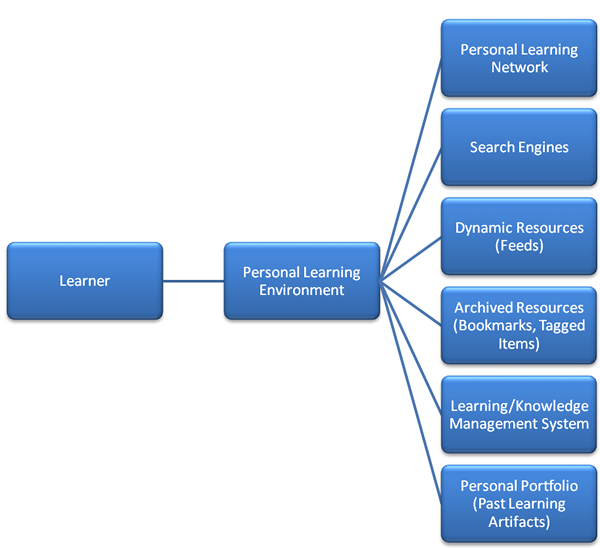

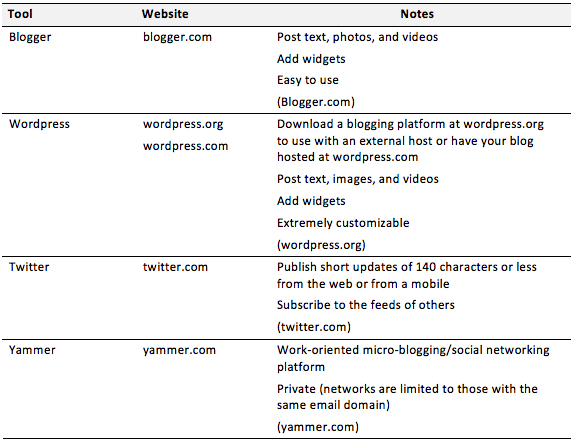

Social bookmarking and research tools allow users to save web pages, articles, and other media (usually to an online storage location) and organize them in personally meaningful ways. Tools that are geared more towards social bookmarking (e.g., Delicious, Diigo, and Twine) place greater emphasis on features that allow users to easily share their bookmarks with friends, colleagues, or the public (Fontichiaro, 2008). Tools that are geared more towards academic research, such as Zotero or Connotea, include bibliographic features, such as citation generators and reference list management. Table 1 introduces several common social bookmarking and research tools.

Table 1: Social Bookmarking and Research Tools

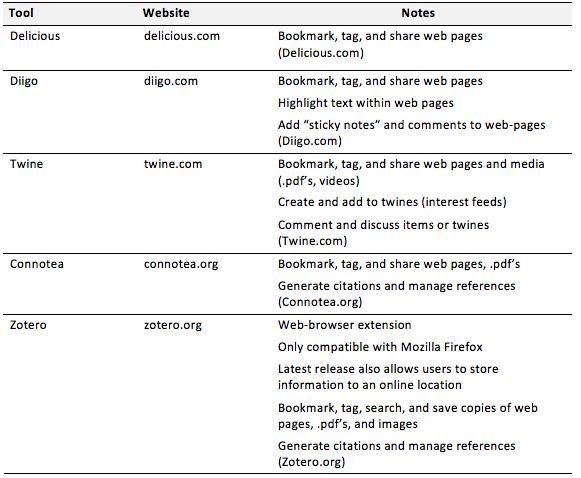

A variety of free and user-friendly tools are available to publish oneself on the Internet. Iskold (2007) sees the range of personal publishing options as a continuum, ranging from content-focused, formal blog posts to socially-focused, informal messages posted on social networking sites, with micro-blogging falling somewhere in the middle. In general, the length and full-featured capabilities of blogging offer learners the opportunity to explore topics in depth and reflect, while the speed and simplicity of micro-blogging lends itself more towards posing questions and collaborative brainstorming (King, 2009).

Blogs have the potential to be used for more than online diaries. Camplese (2009) proposes that blogging be used to create an individualized content management system that publishes, organizes, and archives an on-going activity feed of a student's learning (“Blogs at Penn State” section, para. 3, line 4). Most personal blogging platforms such as Wordpress (wordpress.com) and Blogger (blogger.com) also make it easy to go beyond basic text and incorporate other media, such as photographs, videos, and audio. Besides enriching and enlivening a post, these tools make it possible for an individual to publish artifacts that are ill-served by text-only displays. For example, a student majoring in dance can upload video clips of performances and choreographic studies to create a blog that would serve not only as an interactive document of learning, but also as an audition reel. Similarly, a computer science major can upload a series of his/her programs, receive feedback from readers, and create an online portfolio of his/her work.

Micro-blogs, such as Twitter (twitter.com), allow users to post short messages from their computer or mobile phone. Users can also 'follow' other members to receive a stream of their posts. Proponents argue that technologies such as Twitter are user-friendly tools that allow them to easily "ask and answer questions, learn from experts, share resources, and react to events on the fly" (Boss, 2008, para. 4, line 3). Table 2 introduces several personal publishing options.

Table 2: Personal Publishing Tools

Individuals who follow multiple blogs and/or regularly visit news or media sites may find juggling the disparate streams of information overwhelming. For this reason, it can be helpful to subscribe to these streams (or “feeds”) by using an aggregator.

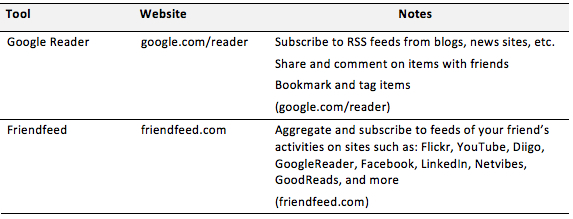

To receive relevant information online, individuals can choose from an array of content managers such as feed-readers and social aggregators (see Table 3). These tools filter online information and collect articles, media, and conversations customized to the user's needs; saving time and effort (King, 2009).

Table 3: Aggregators

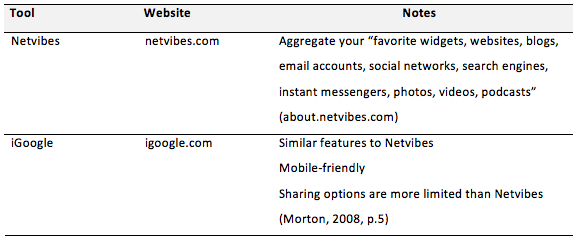

Metagators, also called portals or start pages, can aggregate feeds, social networks, and widgets to create a central, personalized location for an individual's Internet usage (Morton, 2008, para 2, line 1). Using a metagator adds another level to the personal web by allowing one to manage the tools, networks, content, and websites that make up one's day-to-day Internet interactions without the need to visit and log in to multiple sites. Additionally, most metagators allow individuals to customize the layout, appearance, and privacy level of their personalized environment. Two of the most popular metagators are Netvibes and iGoogle (Morton, 2008).

Table 4: Metagators and Start Pages

Widgets are small, adaptable, programmable, web-based gadgets that can be embedded into a variety of sites or used on mobile phones or desktops (Guess, 2008). A large number of widgets are available and many sites allow users to create their own. Learners can use widgets to make other personal web technologies more portable; for example if an individual uses the social bookmarking application Diigo, he/she can use a widget to add a dynamic list of his/her most recent bookmarks to their blog or start page.

Advocates suggest that traditional course management systems could be enhanced by allowing learners the option of embedding their favourite widgets, arguing that these tools could support, “teaching students in a more modular, linked fashion that emulates the way they interact with the online world, rather than the linear world of books and lectures” (Guess, 2008).

PWTs can be combined by the individual to make a personal learning environment (PLE) and to create and manage a personal learning network (PLN). Due to the fact that they are user-created, there is no exact definition of a PLE (PLE, n.d.). In general, a PLE is the sum of websites and technologies that an individual makes use of to learn. PLEs may range in complexity from a single blog to an inter-connected web of social bookmarking tools, personal publishing platforms, search engines, social networks, aggregators, etc. Perhaps one of the best ways to understand the PLE concept is to view the user-generated diagrams available at sites such as the University of Manitoba’s Learning Technology Center’s Wiki [http://ltc.umanitoba.ca/wiki/index.php?title=Ple] and Scott Leslie’s Edtech Post Wiki [http://edtechpost.wikispaces.com/PLE+Diagram].

Users can create an online PLN of colleagues and friends from around the world by joining social networking sites, following and commenting on relevant blogs, sharing resources on a social bookmarking site, or by using a micro-blogging platform. King (2009) suggests that there may be a learning curve for those using technologies such as Twitter to connect to a PLN, but that users stand to gain great amounts of information from their network (“Winning skeptics over” section, para. 1, line 5).

PLEs, PLNs and Mobile Learning

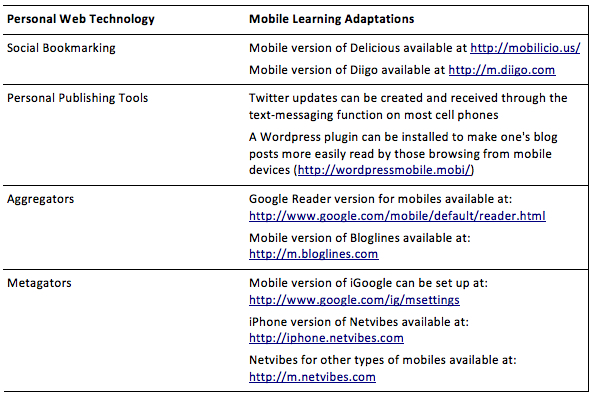

Once an individual creates a PLE or PLN, there is no need to sit in front of a computer to access it. The majority of PWTs have mobile-friendly versions available, allowing individuals to take their learning to go. This can be accomplished in several ways, depending on the mobile device's capabilities and the user's preference. Table 5 lists several examples of PWTs adapted for mobile learning.

Table 5: Examples of PWTs adapted for mlearning

Instead of limiting learning to traditional environments, mobile versions of PWTs give learners more options on where and when to learn. Savvy individuals could use mobile internet devices to confer with their personal learning network while standing in line at the grocery store, listen to the latest podcast on educational technology while driving to work, or begin research for their next project while waiting at the doctor's office.

Due to their small size, mobile devices also allow learners to make records of their learning journey while they are out in the field. Many mobile devices can take digital photographs and videos, which can then be automatically uploaded to a personal blog or a graphic content management site such as Flickr. Using this type of technique, a learner could track a physical situation over time, such as the erosion of a shoreline or the improvements in the sparring technique of a martial arts student, and gather a compelling timeline of visual data to support future reports.

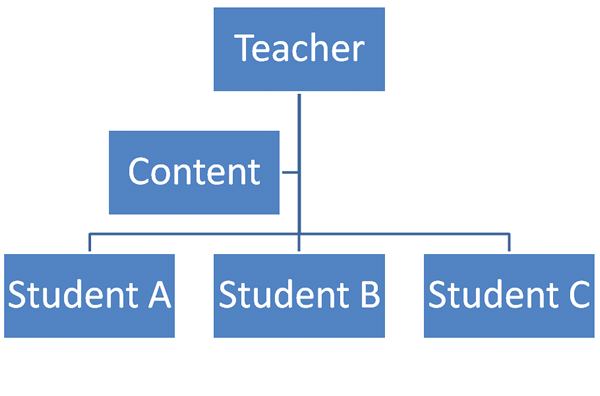

Because these are open-source, free, adaptable, and user-friendly, PWTs can be of great value to teachers, trainers, and students. However, there is a catch: PWTs may clash with traditional, linear, teacher-centered instruction (see Figure 2). Learners who use PWTs must learn to question sources, verify information, compare and contrast various perspectives and become more independent. Teachers who wish to incorporate PWTs into their classroom, especially those who work with children, will need to focus on building critical media and information literacy skills, so that students can effectively navigate the online maze and avoid being fooled by false or misleading information.

Figure 2. Linear Learning, a Teacher selects and presents the content to the students

Figure 3. Non-linear learning; the student receives information from a large variety of sources. The student must choose how to filter, critique, and manage external information.

Richardson (2009) suggests that personal web technologies should be incorporated into K-12 curriculums. Teaching students how to best use these technologies could support both their formal classroom learning and give them a starting point when researching, creating, or collaborating on topics of their own choosing (see Figure 3). Many students have already experimented with a personal web technology, such as social networking, but, "few of them are being taught how to leverage its potential and benefit from the deep learning that can ensue" (Richardson, 2009, para. 4, line 5).

In higher education, PWTs could be of great use for researching, developing PLNs, and creating online portfolios. An undergraduate student who uses a research tool such as Zotero will graduate with a searchable, organized collection of annotated resources that could be valuable in the workplace or in future academic undertakings. Universities can forge online relationships with their counterparts across the world, and encourage online interaction between their students. With the university’s support, students and faculty can broaden their PLNs to reflect a more global reality. Students in fields such as design, journalism, and the arts may find new sources of motivation when they use personal publishing tools to add assignments to an online portfolio.

In the workplace, PWTs could support the model of a learning organization; an organization that promotes continual learning at all levels (Karash, n.d.). PWTs could be used to support learning on the individual level, but they can also be networked together so that relevant information and new insights can easily be shared.

Although personal web technologies have the potential to support all types of learning, they also have potential disadvantages, ranging from distractions to security concerns.

After setting up a PLE or PLN, some individuals may feel compelled to spend large amounts of time trying to digest and respond to the information being sent from their contacts. As the individual becomes increasingly connected to their PLN, they may become increasingly disconnected to those who are physically around them, such as family and friends (Utecht, 2008, “Stage 3” section, para. 1, line 3). Care must be taken to balance online and offline concerns.

Using PWTs to incessantly check for new articles, status updates, and activity may become a drain on one’s attention and productivity (Grossman, 2009). While some phases of work may benefit from collaboration and communication, other types may require the student or employee to disconnect from the web to perform at their best.

Some claim that personal publishing technologies give everyone a voice, leading to a more democratic, participatory learning environment (Pettenati & Cigognini, 2007). However, it is also possible for some well-known individuals (such as Internet celebrities) to dominate the online discussion, by gathering large numbers of 'followers' who amplify their ideas and opinions by supporting and spreading them around the Internet. Valuable or innovative ideas put forth by lesser-known individuals can easily become lost in the noise.

Individuals who wish to learn from their personal network must strive to create a diverse PLN populated with voices that may dissent, challenge, or provoke. Otherwise, the PLN cannot foster critical and creative thinking, but instead functions only as an "echo chamber" that insulates the user from reality (Downes, 2007, cited in Richardson, 2009, “Engaging diverse voices” section, para. 1, line 3).

It is difficult to use most PWTs without giving up some amount of privacy. Personal publishing tools in particular have the potential to make one vulnerable to overly harsh criticism and harassment by commenters. Learners also must take into consideration that anything they publish on the Internet may be found by supervisors, peers, teachers, and future hiring managers (Harris, 2007). Individuals who work with secret or sensitive information must make sure their use of PWTs does not constitute a security risk for themselves, or for their organization.

When learners adopt personal web technologies, it enables and requires them to discard their roles as passive consumers of information and to take on new roles. To successfully use PWTs, learners must become editors who critically question content and sources, librarians who organize and archive resources, and also creators who add their voice to the online chorus by engaging in discussions, collaborating on projects, and contributing their own ideas and media (Bender, 2002, p. 29). Personalized technologies allow individuals to choose not only how they receive and view information, and also how they interact with it.

While teachers and trainers can encourage the use of PWTs and aid in the development of the related skills needed to use them, the true quality and effectiveness of a PLE or PLN depends on the learner him/herself. For self-directed, critical-thinking individuals, personal web technologies present a range of new learning possibilities.

Bender, W. (2002, January). Twenty years of personalization: all about the "Daily Me". Educause Review, 37(5), 20-29. Retrieved April 8, 2009 from: http://net.educause.edu

Boss, S. (2008, August 13). Twittering, not frittering: professional development in 140 characters. Edutopia. Retrieved April 21, 2009, from: http://www.edutopia.org/twitter-professional-development-technology-microblogging

Camplese, C. (2009, January 8). Cole’s page. Not Your Grandpa's Blog. Retrieved April 22, 2009, from: http://eli2009.wordpress.com/coles-page/

Coates, K. (2009, March 23). Knowledge overload. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved March 27, 2009, from: http://www.insidehighered.com/views/2009/03/23/coates

Cohn, E. R., & Hibbitts, B. J. (2004). Beyond the electronic portfolio: a lifetime personal web space. Educause Quarterly 27(4). Retrieved March 1, 2009 from: http://connect.educause.edu/

Fontichiaro, K. (2008, May). Using social bookmarking to organize the web. School Library Media Activities Monthly, 24(9), 27-28. Retrieved March 12, 2009, from: Computers & Applied Sciences Complete database.

Grossman, L. (2009, March 16). Quitting Twitter. Time, 173(10), 50. Retrieved April 10, 2009: from Military & Government Collection database.

Guess, A. (2008, August 12). A widget onto the future. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved March 4, 2009, from: http://www.insidehighered.com/

Harris, C. (2007, April). Five reasons not to blog. School Library Journal, 53(4), 24-24. Retrieved April 22, 2009, from Professional Development Collection database.

Iskold, A. (2007, December 11). The evolution of personal publishing. ReadWriteWeb. Retrieved April 21, 2009, from: http://www.readwriteweb.com/archives/the_evolution_of_personal_publ.php

Johnson, L., Levine, A., & Smith, R. (2009). The 2009 Horizon Report. Austin, Texas: The New Media Consortium.

Karash, R. (n.d.) Learning-org dialog on learning organizations. Retrieved March 30, 2009 from http://www.learning-org.com/

King, B. (2009, March 19). Drinking from the fire hose: finding useful drops in the Twitter deluge. Seybold Report: Analyzing Publishing Technologies, 9(6), 14-14. Retrieved April 10, 2009, from Academic Search Premier database.

Lewis, J. H., & Romiszowski, A. (1996). Networking and the learning organization: networking issues and scenarios for the 21st century. Journal of Instructional Science and Technology, 1(4). Retrieved March 31, 2009, from: http://www.usq.edu.au/electpub/e-jist/docs/old/vol1no4/contents.htm

Morton, E. (2008, March 4). Start-page smackdown: Netvibes, Pageflakes, iGoogle and Live.com. Cnet Australia. Retrieved April 16, 2009, from http://www.cnet.com.au/start-page-smackdown-netvibes-pageflakes-igoogle-and-live-com-339286371.htm

Pettenati, M.C., & Cigognini, M.E. (2007). Social networking theories and tools to support connectivist learning activities. Retrieved April 20, 2009, from: http://elilearning.wordpress.com

PLE. (n.d.) Retrieved March 4, 2009 from the Learning Technologies Centre Wiki: http://ltc.umanitoba.ca/wiki/index.php?title=Ple

Richardson, W. (2009, March). Becoming network-wise. Educational Leadership, 66(6), 26-31. Retrieved April 10, 2009, from Professional Development Collection database.

Siemens, G. (2006). Knowing Knowledge. Lulu.com. Retrieved April 20, 2009 from http://ltc.umanitoba.ca/KnowingKnowledge/index.php/Main_Page

Utecht, J. (May 2008) How to create a personal learning network. ß28(10) p52. Retrieved on April 10, 2009 from: http://galenet.galegroup.com