Academic journals disseminate both new research and the critique of existing research as an important part of the inquiry and knowledge sharing process. Scholars rely on academic, peer-reviewed journals for research on which they can build their own investigations and scholarship. The Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology publishes educational technology scholarship – the journal’s peer-review process is an important part of building a reliable and credible body of research and knowledge in the field. Manuscripts published in CJLT typically include research papers, literature reviews, critical scholarship, position papers, evaluations, case studies, instructional development reports and book reviews. After a manuscript is blinded (i.e., identifying information is removed), the editor selects 2 – 3 peer reviewers who will receive the blinded manuscript for review. Anonymous review of an article focuses critique on the academic rigor, research methods and logic of argumentation rather than on the person(s) who authored the manuscript.

Good academic journals tend to publish competing and even contrasting articles about a particular research field, question or topic – this approach to academic debate, combined with disciplined inquiry, is believed to characterize a vigorous, growing and dynamic body of knowledge and reliable research in a discipline. Canadian academics believe it is a right and a responsibility to analyze, synthesize and critically evaluate the current knowledge base and to identify inaccuracies, faulty arguments and claims that are not well supported with evidence.

A journal’s editor and editorial team manages the peer-review process by which scholarship relating to a particular academic discipline is published. The part of the journal that is not usually peer reviewed is the editorial; the editor often writes an introductory piece to provide an overview of the current issue. In past editorials, this editor has written about the academic publishing process, the editorial and peer review process and the genesis of a new association. For this issue, the editor provides an overview of the six manuscripts and two book reviews that have undergone rigorous peer review. In the second part of this editorial, the editor offers a perspective on participatory Web 2.0 trends that may be of particular relevance to educational technologists.

The first issue of CJLT in 2008 consists of six articles (four research papers, a position paper and a literature review) and two book reviews. The sixteen authors who have contributed their scholarship to this issue are educational technology researchers affiliated with higher education institutions across Canada. The editor is grateful for the 40+ peer reviewers who read and commented on the manuscripts, the members of the editorial team who provided timely feedback on this issue, invited and reviewed book reviews, prepared French translations of abstracts and conducted editorial and peer reviews. Thank you to CJLT’s copyeditor who puts the final polish on each and every sentence.

The first research article in this issue, entitled “Science and Math Teachers as Instructional Designers: Linking ID to the Ethic of Caring”, describes a qualitative study conducted by Rose and Tingley into the relationship between systematic instructional design and classroom teachers’ practices and needs. While corporate, government and military organizations have readily adopted systematic approaches to instructional design, these models and processes have yet to play a significant role in public education. An exploratory inquiry, defined as research for teaching by the authors, was conducted with six math and science teachers, from elementary, middle and high school, to better understand how they conceptualized and practiced instructional design and to gain new insight into the apparent disconnect between the instructional design community and professionals who teach in K-12 settings. A key finding is that good instructional design, from the experienced math and science classroom teachers’ perspective, is inextricably linked to an ethic of caring. The authors describe pedagogical caring as an ethical and professional commitment to supporting the growth and development of others. Rose and Tingley describe how teachers conceptualize ID, the planning processes teachers do use, and the needs that prescriptive instructional design models fail to meet. A profile of each teacher’s years of experience, instructional design stance and changes in practice over time, provide an interpretive lens through which to consider the findings. Preliminary recommendations for how to adapt or modify systematic instructional design models to better accommodate teachers’ needs are offered. A call to action for the instructional design community to explicitly incorporate the ethic of caring in an adapted or new ID model if they wish to play a greater role in K-12 education concludes this paper.

The second article is a position paper entitled “Internet Use During Childhood and the Ecological Techno-Subsystem”, in which Johnson and Puplampu emphasize the role of technology in child development. A new theoretical framework from an ecological perspective is proposed to guide research on the paths of influence between internet use and child development: the techno-subsystem dimension of the microsystem. Ecological systems theory, which emerged prior to the Internet revolution, offers a comprehensive framework of environmental influences on development and situates the child within a system of relationships affected by several levels of the surrounding environment; Johnson and Puplampu focus on the microsystem, which includes immediate environments, such as school, community and home interactions, for middle childhood. Given the increased complexity and availability of technology to children today (i.e., portable audio devices, computers, cell phones, internet, and so on) the authors present a convincing argument that a new techno-subsystem dimension of the microsystem is needed.

The third article in this issue is a French research paper entitled “Pratiques d’enseignement et Conceptions de L’enseignement et de L’apprentissage d’enseignants du Primaire À Divers Niveaux du Processus d’implantation des TIC / Teaching Practices and Elementary School Teacher’s Concepts of Teaching and Learning at Different Levels of Integration of Icts”. Lefebvre, Deaudelin and Loiselle conducted research on the practices and concepts of eight elementary school teachers who are at different stages of implementation of ICT in their practice. The results, taken from interviews and observation, appear to indicate that teachers who are identified as “experimenters” and that tend to use ICT less often than their peers, adopt concepts and practices that lean towards behaviourism. Teachers identified as “collaborators” or “adaptors” and who demonstrate higher levels of ICT integration tend to have practices that are more varied and show evidence of internal representations leaning more towards constructivism. Lefebvre, Deaudelin and Loiselle have analyzed the relationship between the concepts that are evoked by the teachers and their uses of ICTs using the Concerns Based Adoption Model (CBAM), and offer recommendations for future research and practice.

A research paper by Kay and Knaack, entitled “Exploring the Impact of Learning Objects in Middle School Mathematics and Science Classrooms: A Formative Analysis”, is the fourth paper in this issue. A comprehensive review of the literature is presented on the use of learning objects in education in the last ten years, which also serves to identify the gap addressed in this investigation of the impact of learning objects in middle school classrooms. Using a combination of survey and performance measures, the authors collected teacher attitude, student attitude and student performance information about the impact of learning objects from a large sample of teachers and students from three different school boards. Results indicate that teachers typically spend 1-2 hours finding and preparing for learning-object based lesson plans that focus on the review of previous concepts. The top reason teachers cited for using learning objects was to motivate students about the topic. While there was some variation, both teachers and students are positive about the learning benefits, quality, and engagement value of learning objects. Teachers tend to be more positive about the impact of learning objects than students. Student performance increased significantly, over 40%, when learning objects were used in conjunction with a variety of teaching strategies and not just for review. It is reasonable to conclude that learning objects have potential as a teaching tool in middle school math and science classrooms.

In the fifth article, entitled “An Absolutely Riveting Online Course: Nine Principles for Excellence in Web-based Teaching”, Henry and Meadows explore excellence in web-based teaching through literature review and interpretation of their own personal online teaching experience. The authors outline nine principles to guide the design and delivery of online courses. Each principle is carefully described, supported with related literature from experts in the field, and animated through personal narrative. The principles include: the online world is a medium unto itself; sense of community and social presence are essential to online excellence; in the online world, content is a verb; great online courses are defined by teaching, not technology. The authors seek to provide guidance and direction for new online instructors and course developers, rather than prescribing an exhaustive set of principles or a comprehensive guide to online teaching. With current course management systems, social networking tools and environments, and simplified web authoring tools, publishing course materials and content is easier than ever. Content online, however, does not equal meaningful, or even good, learning. Henry and Meadows’ collection of ideas and suggestions for promoting teaching excellence in the online world provides a good framework for ongoing and active debate and discussion about our higher education ideals for web-based teaching.

Remote Networked Schools (RNS) is an initiative by the Quebec Ministry of Education, Leisure and Sports (MELS) to investigate solutions that the use of information and communication technologies (ICT) can offer for the preservation of small rural schools in Quebec, Canada. The implementation of RNS mobilized then – as it still does now – the local capacity for innovation of all the stakeholders involved in this networking effort to improve learning. In the final research article, entitled “Necessary Conditions to Implement Innovation in Remote Networked Schools: The Stakeholders’ Perceptions”, Turcotte and Hamel build on Ely’s work in an investigation of the RNS educational stakeholders’ perceptions of the importance of the conditions that facilitate the implementation of educational technology innovations for the success of RNS in their locations. The authors conducted stakeholder surveys in each of the first two years of the initiative to examine four conditions of innovation: satisfaction with status quo, knowledge and skills, adequate resources and time. A key finding in this study was the stakeholders’ ambivalence about changing their current practices to become more innovative. No matter what their role, teacher, school management, pedagogical consultant, and resource personnel, stakeholders appeared satisfied with the status quo after two years of the initiative. Recommendations from the investigation have influenced Ministry directions in the third year of the initiative.

Two book reviews round out this issue. First, Gene Kowch has conducted a fascinating review of Merrienboer and Kirschner’s (2007) Ten steps to complex learning: A systematic approach to four-component Instructional Design. Second, Kelly Edmonds has provided a detailed review of Middleton’s (2008) Researching technology education: Methods and techniques.

Educational technology plays an important role in connecting diverse people and ideas. On the commute to and from campus, I listen to several podcasts on my iPod (safely plugged into my car stereo, of course). At my desk, I read a few of my favourite blogs, watch online videos, access hundreds of open source academic journals and often meet with students and colleagues in Second Life. As an educational technologist, my general area of research interest is to better understand how ready access to technology processes and products, new media and international networks impact teaching and learning. In particular, I study how adults and children learn with and are impacted by educational technology. A phenomena that has captured my attention lately is the use of Web 2.0 social networking applications, like grassroots video, blogs, wikis and podcasts, and social spaces like del.ici.ous, FaceBook and MySpace, to help to build greater public awareness and mobilize action on social and political issues that haven’t yet been immediately picked up by mainstream media. Here are a few examples of break-through movements that will illustrate the phenomena I like to call social, academic and political spadework in a participatory Web 2.0.

In December 2007, when it became clear that the Canadian government was about to introduce new copyright legislation, Dr. Michael Geist [http://www.michaelgeist.ca/], law professor at the University of Ottawa and Canadian Research Chair of of Internet and E-commerce Law, formed the FCC Facebook group “Fair Copyright for Canadians” [http://www.facebook.com/ group.php?gid=6315846683] to help ensure that the government would hear from concerned Canadians. Widespread concern that the new Canadian legislation would mirror the U.S. Digital Millennium Copyright Act with strong anti-circumvention legislation prompted tens of thousands to join Geist’s Facebook group. Within 6 months, the FCC Facebook group included over 88,000 members / friends. The group almost doubled in size after the June 12, 2008 introduction of Bill C-61 by Industry Minister Jim Prentice and Canadian Heritage Minister Josee Verner. By June 13th, the day after Bill C-61, dubbed the Canadian DMCA, was introduced, members of the FCC Facebook group were encouraged to join or start a local chapter (22 formed across Canada), to meet with their MP and share their concerns over the new bill, and to write to the Prime Minister and Members of Parliament. New members continue to join Geist’s Fair Copyright for Canadians (FCC) Facebook group daily, which is some pretty impressive spadework.

Another example of a politically active participatory Web 2.0 community is CBC’s weekly radio show, “Search Engine” [cbc.ca/searchengine/] also available as podcasts. Jesse Brown, host of Search Engine, used the show’s blog to web-document his many attempts over several months to interview Minister Prentice about the copyright bill. In November 2007, when a copyright bill seemed possible before Christmas, host Brown invited listeners to submit questions for Minister Prentice on the Search Engine blog. While the minister refused to be interviewed until a bill was actually tabled, Brown collected over 250 questions from concerned citizens. In December 2007, a crowd of over 50 protesters invited themselves to MP Prentice’s annual Christmas party and questioned him about his upcoming copyright bill - many of the questions had been originally posted on the Search Engine blog. Brown published video from this party of protesters on the Search Engine website.

In January 2008, Minister Prentice was interviewed on a different CBC show; Jesse Brown lamented that over 300 questions about the upcoming copyright bill, posted on Search Engine’s blog, remained unanswered. When Bill C-61 was finally released on June 12, 2008, Search Engine posted a summary and analysis within a few hours. The next day, Jesse Brown invited listeners to post a copyright scenario on the Search Engine blog in response to the prompt: "what if I ________: is that illegal?" – within days, hundreds of citizens added their questions and scenarios to the Search Engine blog. One week after Bill C-61 was introduced, Jesse Brown interviewed Minister Prentice. Brown asked a number of questions that were distilled from the hundreds posted on the Search Engine blog. After the prescribed 10 minutes, Jim Prentice hung up. Interested listeners can access the entire interview as a podcast or directly from the Search Engine website.

Ironically, Search Engine broadcast the last radio episode on June 19, 2008, though a weekly podcast continues to be published. Within hours of learning about Search Engine’s demise, a passionate response and call to action was published on individual blogs and the Search Engine blog. One quote from a supporter:It is shows like Search Engine (I think this is the only show in Canada of this type) that shines light on issues vital to the prosperity of Canadians in the digital age. This may sound a bit too poetic but I do think canceling CBC Search Engine is like extinguishing a bright torch in our digital democracy. If we want Canadians to stay informed and be engaged in well-reasoned debate, we can’t afford to see shows like Search Engine, an intensely focused source of information, be canceled (emphasis in original). [http://kempton.wordpress.com/2008/06/19/cbc-search-engine-cancelled/]

In this case, the listeners and readers became the leaders and demanded to be heard. On June 20, Jesse Brown discussed the future of Search Engine and acknowledged the exuberant online reaction to the changes. The passionate response from Search Engine’s listeners, from the blogs to Facebook to letters in the Globe and Mail, demonstrate that this interactive, blended media experience was an effective approach to public engagement in current government copyright policy and issues. Jesse Brown’s Search Engine radio broadcast + podcast + blog + multimedia democratic web experience demonstrated from September 2007 – June 2008 how Web 2.0 technologies can be used effectively to influence and change social, political and academic discourse about issues that matter to Canadians – it behooves educational technology researchers to pay attention.

It is one thing for an academic blogger with a funded Canadian research chair, or a Canadian radio / blog host on a government funded broadcast, to share information and mobilize a community of concerned citizens in a democratic country like Canada. What about individual citizen journalists and the role they might play in creating awareness about social and political issues?

A research group at the University of Washington in Seattle that has studied the growing political importance of blogs around the world offers a different perspective on the interactive Web 2.0 culture. In the third World Information Access report, in which the group analyzes blogger arrests, they document 64 arrests of citizens around the world for their blogging activities (Howard, 2008). Phil Howard, assistant professor of communication at the University of Washington, explains the upward trend in arresting citizen journalists, "Last year, 2007, was a record year for blogger arrests, with three times as many as in 2006. Egypt, Iran and China are the most dangerous places to blog about political life, accounting for more than half of all arrests since blogging became big” (O’Donnell, 2008).

For the educational technologist who likes to believe that citizen bloggers are safe to write about whatever they like in North America and England, think again. Blogger arrests in the US (2 in 2007, 1 in 2006) and the UK (1 in 2008) tend to include offenses such as publishing pornography or inciting racial hatred online, activities that very few would defend. Recently, however, in the Great White North, a citizen blogger was arrested for an activity that many would define as free speech – in 2006, Canadian Charles Leblanc was arrested in Saint John, New Brunswick, for photographing a protest for his blog – he was standing among paid journalists who were covering a rowdy demonstration when police arrested him (CBC, 2006). Leblanc, who at the time was homeless, used a donated digital camera and free web space to publish his blog.

For current news on blogger arrests throughout the world, one can also turn to Citizen Lab, a Canadian research group at the University of Toronto directed by Dr. Ron Deibert [http://www.citizenlab.org/]. Citizen Lab is an interdisciplinary research and development group sharply focused on the intersection of the Internet and human rights. Along with colleagues, Deibert conducted a global survey of Internet filtering through the collaborative OpenNet Initiative (ONI) [http://opennet.net/]. In the book, Access Denied: The Practice and Policy of Global Internet Filtering, Deibert, Palfrey, Rohozinski and Zittrain (2008) document and analyze Internet filtering practices in over three dozen countries. In a profile of North America, one learns that while neither the United States nor Canada practice widespread Internet filtering at the state / provincial level, the Internet is far from “unregulated” in either country. For example, unlike in the United States, in Canada the online publication of hate speech is restricted. In 2006, a Canadian lawyer attempted to block access to two internet sites outside of Canada that he deemed hate speech (http://www.crtc.gc.ca/ archive/ENG/Letters/2006/lt060824.htm). Although the Canadian Radio Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) denied this application, the decision recognized that while the CRTC cannot require Canadian internet service provider’s to block content, it can authorize them to do so, and the scope of the CRTC’s power has yet to be explored (Deibert, Palfrey, Rohozinski and Zittrain, 2008). So, it is easy to imagine a future in which the wings of the participatory web can be clipped, if the CRTC chooses to explore the extent of its power.

Both a cross-Canada story, and a related one in Alberta, provide additional insight on the changing political and publishing landscape for free speech and freedom of expression in Canada, both for conventional forms of mainstream media and Web 2.0 environments populated by citizen journalists. Thousands of Canadians maintain and contribute to a personal blog. Several well-known Canadian educational technologists publish blogs that attract a sizable readership [Couros – http://educationaltechnology.ca/couros/ | Downes – http://www.downes.ca/ | Siemens – http://www.elearnspace.org/]. A large group of Canadians publish a political blog. Robert Jago, who is in Ontario, publishes “A Dime A Dozen Political Blog”, [http://rjjago.wordpress.com/], which is a blog about political blogs. Since October 2007, Jago, a self-described conservative blogger, has published “Canada’s Top 25 Political Blogs”, a ranked list of top political blogs. Each month, Jago uses the Google Page Rank + Alexa Rank to generate his top 25 ranked list by rank. Several of the bloggers who have ranked on Jago’s list have been slapped with a defamation suit by a Canadian lawyer (http://ezralevant.com/2008/04/richard-warman-has-sued-me-and.html). If it is true that bloggers and blogs “allow readers to hear the day-to-day thoughts of presidential candidates, software company executives, and magazine writers, who all, in turn, hear opinions of people they would never otherwise hear” (Siemens, 2002), then educational technologists might want to pay attention to governments, groups or individuals who attempt to control or limit what some bloggers can and cannot say.

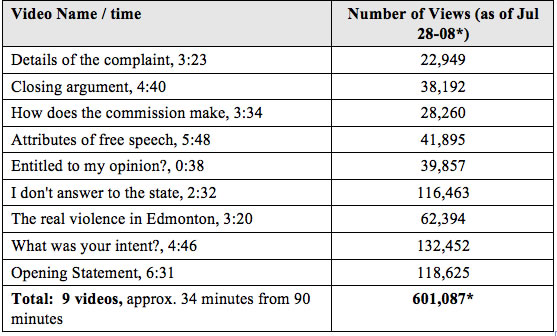

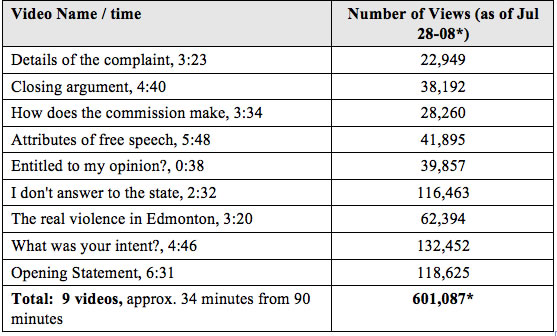

Back in January 2008, one of the Canadian bloggers on Jago’s list carved out a place in blogging history by using readily available social technology to decisive effect. Canadian lawyer, Ezra Levant, kick started a North American debate about freedom of speech and freedom of expression by posting 34 minutes of video on YouTube and blogging about these video clips on his blog. Mr. Levant was under investigation by the Alberta Human Rights Commission (AHRC) for reprinting the controversial Danish cartoons of the Muslim Prophet Mohammed in the Western Standard in February 2006. As the publisher of Western Standard, Ezra Levant was on trial for hate speech as a result of a complaint filed by a Calgary citizen. Somehow, Levant got permission to video record his meeting with the AHRC. He then published nine video segments online accompanied by his sharp critique of the AHRC process in several blog posts. Levant’s YouTube videos about his interrogation went viral (Table 1).

Table 1. YouTube Views of Ezra Levant Videos (Subscribers: 911, as of Jul 28-08)

Dozens, then hundreds of comments from citizens across Canada and the United States began to appear in response to each of Levant’s blog posts. For months, Levant tenaciously blogged about his legal battle with the AHRC; he provided hundreds of links to transcripts, legal documents, other websites and other bloggers’ posts; he posted lengthy legal interpretations about his case.

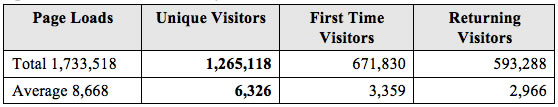

From January to late July, Mr. Levant made over 500 blog postings, many about the human rights complaint he was fighting in Alberta, and also about the cross-Canada human rights complaint being fought by author Mark Steyn, and Maclean’s magazine in British Columbia, Ontario and at the federal level. In June, Mr. Levant live-blogged Mark Steyn's trial, and had 47,000 page loads in 24 hours (http://ezralevant.com/2008/07/thanks-to-my-webmaster.html).

Table 2. Levant’s blogging stats from Jan. 14, 2008 – Jul 28, 2008 3:06 PM (personal communication, July 2008)

Originally, the mainstream media largely ignored the free speech and human rights commission issue. In contrast, by using the blogosphere, Levant was able to engage over a million citizens in a debate about free speech and human rights in Canada, and the role of human rights commissions in controlling hate speech online. The blog community created awareness about the issue of free speech, and the debate in the blogosphere served to make transparent and denormalize the practices of the provincial and federal human rights commissions, and has exposed policies and practices to scrutiny. The blogosphere has lead to increased exposure by major media outlets (i.e., Rex Murphy on CBC, Mike Duffy on CTV, TVO, George Strombolosis, etc.) and, likely because Mark Steyn’s (2006) book is a bestseller, the attention of book sellers (i.e., McClelland & Stewart will publish Levant's book in 2009). As recently argued by Savage (2008) on her blog [http://blog.Maclean’s.ca/author/luizasavage/], “A lot of people don’t like Levant and a lot of people disagree with him and a lot of people are offended that he published the Muhammed cartoons in his magazine”, however this is not a right wing or left wing issue; free speech and freedom of expression are much bigger issues that Ezra Levant, Mark Steyn and Maclean’s magazine. This participatory web case demonstrates how a citizen journalist using a blog and open-source video can make an opaque government process more transparent and influence the social and political culture in ways that rival the mainstream media.

Free speech and freedom of expression are foundations of a democratic society. As educational technologist researchers, it is our right to teach, to learn, to design and develop learning processes, to conduct research and to publish free of government influence or threat of reprisal and discrimination. For this editor, who is against book bans, it seems un-Canadian for a Canadian publisher to face a human rights tribunal for re-publishing controversial cartoons in a Canadian publication. In a country with few internet restrictions, it seems un-democratic for author Mark Steyn and a Canadian media organization, Maclean’s, to have to defend their right to free speech in two provincial and one federal human rights commissions for reporting on an issue of public interest.

Aside from the threat to freedom of expression and free speech online, it occurs to me that there are more than a few educational technology research topics of interest in these participatory web cases. Geist has demonstrated how Facebook, a social networking environment originally created in 2004 by a Harvard University student to connect students on his campus, can be used by an academic researcher and activist to share up-to-date information and to mobilize citizens who share a concern and hope to influence government policy on copyright in 2008. It is worth studying how Geist conceived of and designed his blog, his extensive website, the Facebook group, grassroots videos, and how he utilizes Web 2.0 environments along with the mainstream media to build awareness, persuade people to join, bring people together on common issues, and mobilize a large group of people to act on their beliefs about copyright.

There is a role for educational technologists to play in better understanding the case of a radio host using a combination of mainstream media, blogs, grassroots video and podcasts to build public awareness about copyright and to mobilize citizens to actively question government about policy. A research program could be designed to better understand how participatory Web 2.0 media and methods, like Brown’s Search Engine, might be better used in public education and to increase public engagement in current issues and debates. How might we harness the innovative instructional design, development and utilization of Web 2.0 environments, using approaches like CBC’s Search Engine, for social studies in high school, or political science on campus?

As the Web 2.0 culture continues to unfold, expand and evolve, the field needs to keep a sharp focus on issues relevant to educational technology and the larger academic research community. First, the groundswell of participation in interactive online communities, like those created by Geist, Brown, and Levant, has forced issues like copyright and human rights online from marginal to mainstream status in record time. These issue-centered Web 2.0 communities have motivated and mobilized thousands of citizens to act. Second, there is a clear link between freedom of speech, freedom of expression and academic freedom. For example, in what ways are participatory Web 2.0 mashup environments influencing and changing education in democratic and non-democratic societies, and the social and political contexts in which we live and work? Has the exponential growth of grassroots video, the blogosphere and augmented reality affected how we think about designs for socially and politically active online communities? What happens to academic and political debate and decision-making if the diverse perspectives published online, some of which may be regarded as unpopular or unsavoury, are silenced?

Educational technology researchers understand the power of technology to connect people and ideas. Educational technologists understand the dynamic connections within, between and beyond various disciplines of study as they design meaningful and innovative learning environments for diverse learners. “Educational technology is the study and ethical practice of facilitating learning and improving performance by creating, using, and managing appropriate technological processes and resources” (Richey, 2008, p. 24; Januszewski and Molenda, 2008). Educational technologists know that learners require ready and reliable online access to an ever expanding knowledge base and to each other around the globe – today’s social networking, augmented reality and Web 2.0 capabilities put powerful communication tools into the hands of every citizen. However, unless free speech and freedom of expression are better protected in the online and print media world, then whose voices will be heard, whose will be silenced, and who will decide?

A participatory web provides an opportunity for every citizen to publish their perspective on issues; Canadians must continue to enjoy open and unfettered access to both the popular and politically correct opinions, and those that some might find unsettling or even contemptible. If parts of the knowledge base are suppressed or silenced, if only politically correct opinions, perspectives and ideas are sanctioned, then our ability as researchers, teachers and as citizens to hear the voices we might never hear (Siemens, 2002), to identify inaccuracies, to expose faulty arguments and to challenge unsupported claims is compromised. I am an educator who believes that free speech and freedom of expression are too important for Canadians to give up just because preserving these rights for all citizens might make some of us uncomfortable, or expose us to views we would rather not hear. I am genuinely concerned that the rights to free speech and freedom of expression in Canada are under attack, and that current and future rights will erode unless researchers, journal editors and scholars from across disciplines advocate for the preservation of free speech and freedom of expression across all delivery media. Is the educational technology community content to leave it up to quasi-official government bodies to decide whose voices get heard and whose voices get silenced online?

As Beckwith wrote in 1998:

Educational technologists can be recognized by the stars in their eyes. They know they are sitting on the most explosive potential of the century. Theirs is the apex of innovative motivation. Whether they are fashioning learning environments, creating media, designing instruction or effecting research and theory, educational technologists have a dream-a dream that can sustain them, and those they touch, well into the next century. (p. 3)

Educational technologists need to continue to study and understand the explosive potential of innovative Web 2.0 technology, media and networks in political, economic and educational contexts of democratic free speech and freedom of expression. There is an important role for educational technologists to play in investigating the design, development and utilization of participatory Web 2.0 networking environments, like blogs, wikis, podcasts, Facebook, and so on to create public awareness and to capture and share and reflect current information, to form and mobilize communities of citizens, and to promote social action and participation in academic debate and democracy.

References

Beckwith, D. (1988). The future of educational technology. Canadian Journal of Educational Communication, 17(1), 3–20. Retrieved April 4, 2007 from: http://www.amtec.ca/site/publications/journal/pub.shtml

CBC News. (2006). Blogger's obstruction trial to test definition of journalist. Available online: http://www.cbc.ca/technology/story/2006/11/02/nb-bloggertrial.html

Deibert, R., Palfrey, J., Rohozinski, R., Zittrain, J. (2008). Access Denied: The Practice and Policy of Global Internet Filtering. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Howard, P. N., and World Information Access Project. (2008). World Information Access Report - 2008. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, 2008. Available online: http://www.wiareport.org/ index.php/2008-briefing-booklet/

O’Donnell, C. (2008). International arrests of citizen bloggers more than triple. University of Washington News, June 10, 2008. Available online: http://uwnews.org/article.asp?articleID=42417

Siemens, G. (2002). The Art of Blogging—Part 1. elearnspace, December 1, 2002, http://www.elearnspace.org/Articles/blogging_part_1.htm

Steyn, M. (2006). America alone: The end of the world as we know it. Washington, DC: Regnery Publishing, Inc.