Authors

Michele Luchs taught English and Media Education at Royal West Academy, Montreal. She is currently developing the media literacy component of Quebec’s new English Language Arts curriculum. Email: micheleluchs@yahoo.com

Winston Emery is Associate Professor at the Faculty of Education, McGill University, Montreal. Email: winston.emery@mcgill.ca

Abstract:

In this exploratory casestudy we look at student media production to find out what students know and have learned about the media through production work. We used a media education conceptual framework developed by Dick as a means of describing the day to day media learning of a group of ten students, four girls and six boys, producing a video documentary on rape. We found that as they worked, the students encountered most of the concepts of Dick’s framework; however, with the exception of the development of a sophisticated understanding of the documentary genre, there was little formal opportunity for the students to articulate their nascent critical consciousness about the media.

Résumé:

Dans cette étude de cas exploratoire, nous examinons une production graphique effectuée par des étudiants pour découvrir ce que les étudiants savent et ont appris sur les médias par l’intermédiaire de ce travail de production. Nous avons utilisé un cadre conceptuel d’étude des médias, mis au point par M. Dick, comme moyen afin de documenter l’apprentissage quotidien des médias par un groupe de dix étudiants, quatre jeunes filles et six jeunes gens, qui ont réalisé une vidéocassette sur le viol. Nous nous sommes rendu compte qu’à mesure que leur travail avançait, les étudiants ont rencontré la plupart des concepts inclus dans le cadre de M. Dick. Cependant, à part le fait qu’ils aient développé une compréhension approfondie du documentaire, les étudiants ont eu peu d’occasions formelles d’exprimer leur conscience critique émergente à l’égard des médias.

Over the past fifteen years, media educators have attempted to evaluate the success of media education curricula and teaching in developing in students’ critical literacy. Although there is much anecdotal evidence of the enthusiasm of students in media literacy courses, relatively few studies of what they actually learn have been conducted. McMahon and Quin’s (1992) large scale assessment in Western Australia was based on a posthoc objective test, requiring high school students to analyse a series of print advertisements and a segment of a television situation comedy. Although the study found that students’ technical knowledge about media was strong, the results were disappointing on those items, which tested the reflective and critical understandings of media education (i.e., the ability to link media codes to cultural values, to use concepts of preferred meaning and to provide examples of the social outcomes of stereotyping). The study’s findings tend to be supported in a few smallerscale studies, which have generally asked students to analyse media texts by answering standardized test questions or writing formal analytical essays. The “disappointing” results may have more to do with methodological weaknesses in the approaches to assessment used in the studies, than as real reflections of what the students don’t know; they may also have something to do with the rhetorical sophistication students are expected to display in formally writing about their understandings. Finally, there is scant description of the pedagogical practices used with the students. We are not told, for example, whether the pedagogy cultivated the sorts of understanding that the researchers attempted to measure and the extent to which the researchers analysed the teaching.

One of the ways we might be able better ascertain what media education students understand at a deeper level is to look at their media productions. In Cultural Studies Goes to School, Buckingham and SeftonGreen (1994) interview students about their media work, elucidating the sophistication with which young people actively use popular media as resources for creating their own meanings and identities. They investigate the complex relationships between students’ “spontaneous” knowledge of the media and the “scientific” knowledge they are expected to represent at school. Using surveys, in-depth interviews and student media work as data, the authors demonstrate that students do, indeed, critically evaluate media messages, although not necessarily in the ways teachers or some researchers might expect. In subsequent studies, Buckingham, Grahame and Sefton-Green (1995) investigate various aspects of production work in a variety of settings. Besides amplifying the complexity of understandings that students explore and develop out of production activity, they raise some interesting problems teachers encounter in planning and implementing student productions.

In this exploratory casestudy we look at student media production to find out what students know and have learned as a result of producing a video documentary. The research methodology we adopted for this study is qualitative. (Bogdan and Biklen, 1992). Our study reflects the following characteristics of the qualitative paradigm:

The study was conducted at a comprehensive secondary school in St. Léonard in northeastern Montreal. The school has been in existence for 34 years, and, at the time of the study was the only English language high school in the school board. Most of its approximately 800 students are from St. Léonard, a largely middle-class Italian community.

Ninety percent of the Secondary V1 students receive their high school leaving certificate, and a large percentage go on to CEGEP (Quebec’s colleges of general and specialised education) and, subsequently, University. Media Education is an elective course, and because most honours students opt for advanced science and math courses in order to gain entry to academic programs in CEGEP, Media Education classes are comprised largely of regular stream and special education students. Forty percent of the students who take Media Education classes in Secondary V are considered “borderline” learners.

In the Secondary V Media Education program, students investigate how graphic, video and photographic images are designed and how and why they respond to the images. During the course of the year, students wrote scripts for television commercials, cooperatively produced video public service announcements and a video documentary, restored an old photograph, and cooperatively produced a photographic advertisement using desktop publishing software.

In our study, we followed a group of ten Secondary V students - four girls and six boys - as they produced a video documentary on rape. Prior to Michele’s entry to the school to collect data, the students had already decided on the topic of their documentary and had lined up a victim to be interviewed.

Both Winston and Michele had considerable insider knowledge which they brought to bear in collecting and organizing, and, ultimately, analysing the data. Winston had been working with Frank Tiseo, the teacher of the class, for a number of years, visiting his classes, helping students evaluate their productions, and participating in year-end presentations of student work at the school. He often invited Tiseo and his students to present their productions to classes of pre-service teachers at McGill’s Faculty of Education. Michele had previously practice-taught under Tiseo’s supervision at the school and had conducted classroom research there while in her teacher education program. Michele returned to the school as a graduate student to conduct this study, under Winston’s direction. She visited the school each day the students had media education class for the 15 weeks between mid-January and early June. She also interviewed the teacher after each class.

Winston visited from time to time to observe the students at work and to interview the teacher. Although our experience and expertise can be regarded as a source of bias, the “insider” (Cochran-Smith and Lytle,1993 ) knowledge - knowledge and trust gained through spending considerable time with the teacher and students enabled us to generate and interpret credible theories of action in the classroom (p.16).

The main sources of data for the study included: detailed field notes of student conversations as they worked to produce the documentary; daily informal interviews with Tiseo and a formal interview two weeks after the end of the class; formal and informal interviews with students before and after class and in-between activities. We also examined teacher-produced materials distributed in conjunction with the video production activities of the class and student-produced materials such as treatment plans, scripts, crew responsibilities and, of course, the finished video documentary itself. From time to time we will augment data derived from this case study with observations made of a group of students in the same class who produced a public service announcement on gun control and a group of students Michele worked with the previous year to produce a documentary on the Hare Krishna community of east end Montreal.

The documentary the students produced was one of four major projects they undertook over the school year. Furthermore, while working on the documentary, students were simultaneously engaged in at least one other project. This occurred partly in order to make efficient use of equipment and facilities in the school, and partly because of the teacher’s philosophical and pedagogical stance, which emphasizes integration of subject material with `real-world” tasks and problems and self-direction.

In November, the teacher had set an assignment for each student in the class to write a half-page treatment for a short documentary, a public service announcement or a commercial. The students had to include the following information as a minimum: the target audience, the message they wished to convey, important phrases, e.g. “tag lines”, that would convey the message, and descriptions of the visual images that would appear on the screen. At the next class, the students formed production teams and discussed each treatment in order to select one treatment to be produced. Having selected the treatment, the group then discussed its elaboration: suggestions were made for improvement of the original idea, for more details of the treatment, extension of the visual imagery, dialogue etc. The originator of the treatment took this information and then, alone or with collaborators, developed a more complete script. It is at this point that models of initial scripting (proposals, storyboards, scripts, shooting scripts) were given to the students so that they could represent their ideas more conventionally. By this time, too, the group had presented their proposal to the teacher. Mr. Tiseo often gives advice - in this case he cautioned the students that although the subject had not been done before, it might be difficult to find a rape victim willing to be interviewed - but generally leaves the decision to proceed to the students. Once a final script has been prepared - and the students have followed the process of producing it - each student is required to rework his/her original treatment into a formal script and submit it to the teacher before the end of the marking period.

When Michele arrived to observe the students in January, they were working on various aspects of pre-production: researching the subject of rape, making arrangements for shooting dates, becoming familiar with the video equipment, and developing and editing interview questions to ask the victim and her father. Over the next two and a half months the students planned and shot the footage, and edited the final version. An important pedagogical feature to be noted about this whole procedure is the extent to which instruction was geared according to student need and progress. The students, at the same time they were developing their text, were learning the technical aspects of communicating through the video medium. Tiseo provided “guides” - packages of instructions/information - on all aspects of video production which the students used to prepare to shoot their footage. Tiseo demonstrated operation of equipment to a very small group of students who, in turn, taught other students, so that each student in the class was familiar with most technical aspects of the production process as well as the design and organization of the documentary itself. This stance of allowing students the ownership of the media texts they produce, providing them with the resources to produce a good product and, at the same time, critiquing and questioning students about production techniques or the substance and quality of the texts as they are engaged in learning, seems to us to be an important one to the successful implementation of a production-based media education curriculum.

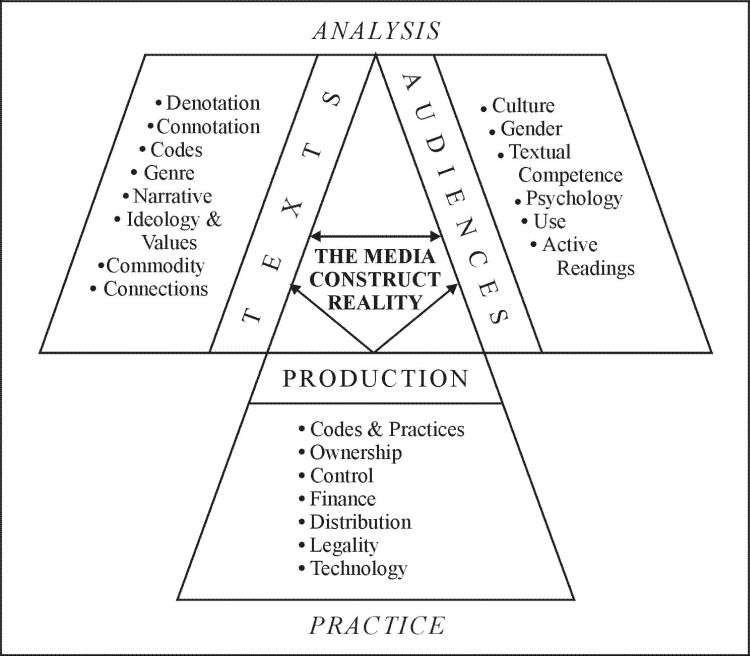

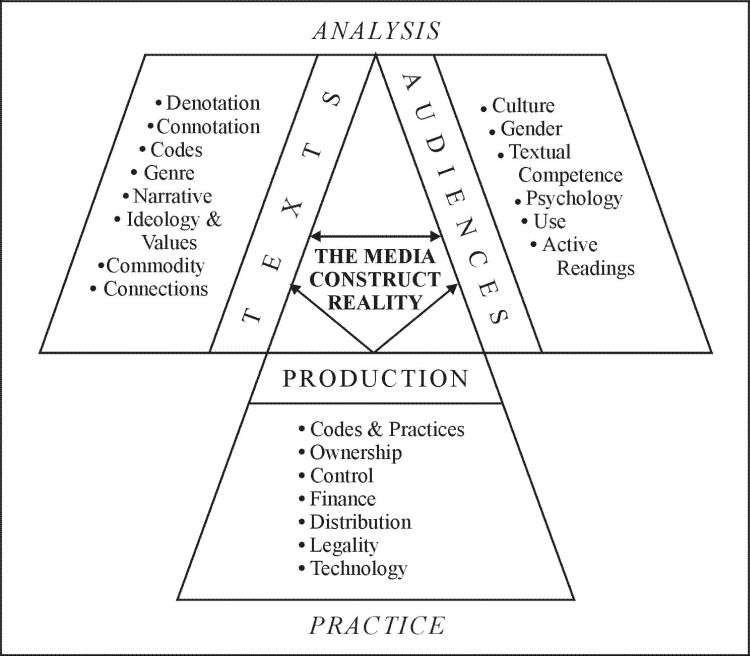

We have chosen a conceptual framework of media education developed by Dick as a basis for describing what happened as the students produced their video documentary. Media education theorists and curriculum writers have used the framework. It identifies the specific interrelated concepts students should be aware of and deploy in their responses to and analyses of media texts.

Generally speaking, media education curricula in Canada have been developed around the Text and Production components of the framework. They comprise, largely, analysis or deconstruction activities that deal systematically with framework elements. There are fewer accounts of how teachers deal with Audience. Most of these centre on discussions among teachers and students of their own and others’ responses to media texts and the factors that may account for the nature of - usually the differences - the responses. What is characteristic of the teacher- centred and - organized analysis approach is its systematic nature. Concepts are usually taught one by one within coherent (to teachers, at least) units of instruction so that students accumulate over time a sense of how the framework fits together, enabling comprehensive analyses of media texts according to prescribed protocols.

Figure 1. A Model of Media Education in Shepherd (adapted from Dick), 1993

However, as Dick has indicated by the inclusion of arrows between the components, there is considerable interaction among and overlap between concepts. What we found when students produced texts was that framework elements bubbled up in unsystematic ways with considerable overlap of concepts occurring as the students generated understandings of what they were doing as they produced their own texts. For example, while the rape documentary group explored the different possible directions their story could take (narrative), they simultaneously dealt with how the interaction of a visual attack sequence, music and narration formed their message (denotation, connotation, codes, conventions). At the same time, audience characteristics like culture and gender shaped the way the students viewed their own video footage, how they perceived the interviewees, the nature of the questions they planned to ask them, and the eventual production choices they made when editing the interviews. Although we are focussing on the group who produced the rape documentary, we have included observations of the activities of two other video production groups (Hare Krishna documentary, gun control public service announcement) to elucidate the data.

As they learn the procedures of producing media messages students come to understand more about the constructed nature of the texts of each medium. We argue that because they actually create texts, students should quickly pick up on their rhetorical nature. Evidence that this was true for these students was most apparent in their understanding of genre.

When the students were initially developing interview questions, most of them felt that they should just ask the girl to tell her story, point the camera and record the finished documentary. That was how it happened on the news and in documentaries. If this didn’t work, perhaps they could tell the girl what they wanted to hear. Fred2 explained to his peers that this would be the best way to understand what the girl went through, “in her own words.” Having someone ask too many questions, he continued, “would just cut it up.” In a later group discussion before beginning to shoot, Selena asked Tiseo why they needed to cut up interviews when they edited:

She asked if it wasn’t better to run the interview with the father and the daughter without interruptions. Tiseo told her that they needed to edit to juxtapose the interviews together; and would only use the sections they wanted. Selena responded, “Sir, do you do that often? Personally, I think that if we are doing a serious topic like rape, we shouldn’t cut into the girl’s interview at all.” Tiseo asked her if she didn’t see that technique used on programs like Fifth Estate [inter-textuality] Selena answered, “Not unless their subject is, like, a shady car dealer. That’s when they use fast, choppy images.” (Fn. March 21)

We can see Selena’s conceptualization of this documentary as being simply an uninterrupted recording of the narrative by the rape victim, followed by that of her father. This concept apparently has something to do with the “seriousness” of the topic and with the perception that coherence was due to the clarity of presentation by the subject(s) of the documentary rather than its producers. We wonder whether this notion is generalized to all “serious” video texts. Is there a general perception among these young people that the documentary is to be “real” and, therefore not as constructed as other genres of television? And, yet there is some ambivalence here - if the subject is “...a shady car dealer...” then, perhaps the documentary maker could use fast choppy images, or could cut into the interviews.

After they viewed the interview rushes, Tiseo asked them to start thinking about sections of the father’s and daughter’s interviews that they might juxtapose. He also told them to make a list of other scenes they would need to shoot, to cover narrations. (Note that the students had already decided that there would be voice-over narration to “...explain things to the audience.”) One of the `fillers’ the group decided to use were quick interviews with secondary V to get their opinions on rape. They set up the interviews in a hallway, “... to give the impression”, said Angel, “of questioning students at random”. (The students to be interviewed were carefully chosen by Selena, Gia, Angel and Tiseo. In an out-take, one can hear a participant ask how long her answers should be.)

A few students also suggested creating a dramatization of the rape. Selena told them, “ everybody knows what rape is. We don’t need to show it.” Angel, Rock and Fred responded that the short documentaries they saw on television always seemed to include some sort of re-enactment. The students were inter-textualizing their previous experience with the documentary genre, to choose scenes that needed to be shot. They were starting to think of the documentary as being a series of elements that were woven together to create a story. In an interview held toward the end of the production process, Selena demonstrated this change in her understanding of the constructed nature of the documentary genre. She explained:

We viewed everything and thought about what we could take out of what we had filmed so that it would make sense... At the beginning, I thought you could just show interviews as they are, I mean rape is a serious subject! I think that if we hadn’t cut any of the material, though, there would have been no story. It would have just looked so corny, very non-professional. (Int. May 3)

After experiencing the production process herself, Selena no longer saw her documentary project as simply presenting the truth or the way things are. Her final comment seems to suggest that she had re-evaluated her assessment of other documentaries seen in light of her understanding of the constructed nature of her own project. It would have been interesting to see how her knowledge transferred when analysing programs in the same genre or other information-based texts like news reports.

On the whole, the program is competently produced. Technical quality, from the manipulation of the cameras to lighting, audio and editing, is very high - this from a group of students who, prior to this project, had no previous formal experience in television production. Furthermore, the presentation is original. We have seen no professional production that has treated the subject in the way these students did. Some of the earlier literature regarding production in media education, at best, seems to take the competencies described above for granted or, at worst, comment on how poor student productions are relative to professional productions. The students we studied spent considerable time practising and perfecting technical operations and getting the conventions of the medium right, before. This may have something to do with the teacher’s level of expertise in setting up the assignment, his judicious choice of equipment and the way he arranged for the learning of technical operations - operations manuals which include proper handling, student tutors, and frequent reminders about how to handle equipment with care. In any event, the program shows considerable competence in the design and presentation in documentary video form.

During the production exercise, the students had to consider how visual and sound effects added to or changed the mood, tone and underlying message of their piece. Through their production choices, they explored the denotation (meaning) and connotation (underlying meaning) of their piece.

On March 8, a few days before J. (the rape victim) and her father were to be videotaped, Tiseo found out that the switcher was not working. Instead of being able to shoot from two different angles and switch between cameras in the control room, the students would have to carefully choose their shots beforehand, since they would be using only one camera. Tiseo had the group set up the portable equipment and practice different camera angles. He suggested using a medium shot or a close-up; although, “if the shot is clear, and the interviewee gets intense about a question, the camera operator could do a slow zoom in on her face.” Angel asked why. Tiseo explained that this technique was often used in television and film to let the audience know that the person being interviewed was making an important point. For the rest of the class, the camera person practiced slowly zooming in on Selena, who pretended (uncomfortably) that she was giving the interview.

During the next class, the students decided on set design. In the studio, there was a Venetian backdrop in place from a previous commercial shoot. When Rock, Angel and Selena saw the shot on camera, they felt the bright busy backdrop detracted from the seriousness of their subject. They felt that white would look too bland. Selena and Dino pulled out a black backdrop. The group liked it. When Tiseo told the others that he thought the black was too grainy, Rock answered, “No, it isn’t sir. It’s terrific. It shows the pain that the girl went though.” The other students agreed.

Selena suggested adding a plant to make the set look more “homey.” Tiseo told her it would make it look too much like a Channel 9 video (volunteer cable station). Dino suggested that they shoot the father on the black background as well. Tiseo told him that they would have a problem with jump cuts when they edited. “Besides,” said Rock, “they had different experiences of the rape. They can’t have the same background.” The group decided to shoot the father in front of the computer lab, to give the impression of filming him at the office.

Through positioning of the camera and framing, the students realized that they could direct the viewer’s attention to what was important. They learned the codes and conventions of television and film to express emotion. The students also experimented with how background visuals and sound created the illusion of mood and place. Rock even equated the settings as symbolizing or connoting how the rape experience was lived by J. and her father. On a more technical side, the students learned that shooting the two main interviews on the same background would make editing their piece much more difficult (codes and conventions).

Tiseo’s students experimented with creating mood through lighting and camera angles more thoroughly when they shot an attack scene in the television studio. The students had originally hoped to re-enact the rape scene. In a pre-production meeting, Fred described how it might look: “We could shoot it in the bedroom. We would see a window open, and a leg coming through. The next shot would be a close-up of the girl’s face looking scared. Then we’d see a hand covering her mouth.” Tiseo reminded students that they would have to think of what could be realistically shot in the studio. The students decided to create a more generic attack scene. For a set, they used a park bench and lamppost set against a black background. Tiseo suggested that the group shoot their scene in negative style, which “would eliminate the boo-boo’s.” The students used medium shots and close-ups, making it difficult to tell where it was shot. The footage had an eerie nightmarish quality. Although Angel would have liked more detail, Tiseo stressed that no one would doubt was happening. He said, “The shots work because there is a lot of action and no detail.”

The students were not completely satisfied. Angel, Rock and Selena felt that many of the shots they had taken looked the same. Tiseo suggested combining their footage with another attack scene that had been shot by a group several years before for a public service announcement on self-defence. After some discussion, the rape group decided to edit part of the public service announcement in under the concluding narration. Although they did not recreate J.’s episode, the students felt that the attack scenes underlined their message that rape is violent.

Towards the end of the editing process, Tiseo asked the students what sort of music would be appropriate under the narrations and at the beginning and the end of their video. Angel said, “We need to find music to match the mood of the video.” Gia added, “We need to find words that express the pain that J. went through.” Students suggested different songs that were currently popular. Tiseo explained that whatever they chose would need to be copyright free (Codes and Practices, Ownership, Control, Legality). During the next class, Fred brought in one of his band’s songs, about the pain a boy suffered when he lost his girlfriend. Selena, Angel and Gia told him that they liked the song, but felt the voice should be a girl’s. Selena brought in some dance music produced at her brother’s studio, sung by a woman; but the group felt the up beat gave the wrong message. Finally, the group decided it would be best to use an instrumental piece. “This way”, said Selena, “the audience wouldn’t get mixed up in the songwriter’s words, but would listen closely to what J. had to say.” Selena asked her brother if he could record some simple music on the synthesizer.

The group members were aware of the rhetorical importance of music in their video, i.e., to establish and underline the mood (connotation) to focus the audience on the seriousness and horror of rape. The music could not be too up beat or happy, because it needed to emphasize the pain of J.’s experience. Nor could a boy sing it, because it would take the focus away from J. as a woman. The group finally decided that even words might distract the audience from the intro and extro commentary, and thus, opted for the instrumental.

In April, Rick, Angel and Gia were previewing footage of students, shot outside the school, to be used in a Voice-Over (V/O) narrative sequence. Gia, who had not been on the shoot, asked Rock to turn up the volume. He explained that they had filmed without sound, but would add music and commentary later. Gia said, “I can’t stand to watch TV with no volume. I want to know what people are saying.” Tiseo explained that sound was often recorded separately and told them about a group of students making a public service announcement on gun control. In the visual sequence of the PSA, while the mother washes dishes, her bored son pulls out a gun from a drawer in another room and shoots himself.

The group had several work sessions with Cliff Hogan, the school’s audio-visual technician to discuss what the audience should hear. Group members’ suggested: dishes being washed, the radio playing (Should it be French or English? Music or news?), the mother humming, toy trucks moving back and forth, the boy making a truck sound, a telephone ringing, a drawer opening; and the sound of a gun going off. Santino, the soundman, couldn’t believe that it took one class period to shoot the video and four class periods just to record the sound. He said, “It took one whole period just to get the gun shot right. We tried bursting a paper bag, beating a bat on a wooden table and using reverberation, and finally ended up blowing up an apple with mini firecrackers. That one sounded the most real.”

In the above instances, by creating the soundtrack separately from the video track, the students not only developed awareness of the constructed nature of the video text, but also enhanced their understanding of the rhetorical qualities of sound and its impact on audiences.

Narrative is one of the media’s dominant techniques for shaping events. According to Masterman (1985), it is important to consider media texts as narratives, since familiarity with narrative strategies will be transferable to a wide range of media genres and to any new media text. Narrative study also raises the central concern of media education: “the constructedness of what are frequently portrayed as natural ways of representing experience” (p. 175).

The first time the students viewed the interview tapes, Gia said, “I hate hearing Angel and not seeing her. Why did we do that?” Angel had asked her questions off camera. Angel reminded Gia that they would edit her questions out when they assembled the program. The students began their work on the narrative: deciding which sections of the interview to include, determining what other visual footage they would need, shooting the attack scene, and developing questions for and shooting interviews with other students at their school.

Tiseo told them that the footage they had shot contained their story. They had to think about how to pull the elements together and sequence them coherently. He discussed the different techniques that could be used to create the narrative. He had them practice creating narrative by cutting the shots of the attack together. Selena said, “We thought about what we could take out so it would make sense. Even though we cut it, it did not show. Everything went into place. It was like nothing was cut. We were in shock!” The students decided to use the attack shots under the introductory narration. According to Angel, this would get the audience into the feeling of their piece.

The students then started editing the interviews. Tiseo asked them to think about how different pieces of the interviews could be juxtaposed. He told them that how they decided to pull J.’s story together made a difference in the message conveyed to the audience. The group decided that the first segments would concentrate on J.’s description of the event and her father’s reaction to it. Following a narrative bridge would be her description of what happened after the event (police, courts, attacker not arrested). In the third section, they would present how J. felt now about dating and relationships.

On May 25th there was a major discussion about the overall shape and direction of the video. In addition to the interviews with J. and her father, the production team had spoken with a number of students at the school about the issue of rape. The team had intended to include these interviews near the end of the program. Tiseo asked, “What if we just brought in the student interviews and didn’t see J. any more? How do you think that would fit in?” Angel, Rock, Gia and Selena were uncomfortable with that. Angel said, “If we bring J. and her father back, does it mean we can’t use the student interviews?” Tiseo told them that the student interviews brought up interesting ideas, but didn’t go in the same direction as their piece so far:

Imagine watching this 5-minute pattern with the father and the daughter in parallel editing, with a few narrations. All of a sudden you shift gears and insert another sort of narration to set up the student interviews. We would have to contrive a narration to bring them in. (FN, May 24)

Angel answered, “We can’t afford to do that, even if it’s only Selena’s. Right now we have no choice. We only have enough visuals to cover one more narration.” Selena agreed that it was best not to include the student interviews.

The group decided to end the story on a positive note, concluding with J. affirming the importance of having positive relationships with men. Selena said, “We left people with the feeling that even when you go through something horrible like rape, you can put it behind you and move on with your life.”

Producing a video is a lesson in storytelling. The students in the group started with other people’s narratives and crafted a story that was very much their own. They followed a standard narrative model of establishing a problem, elaborating on the problem and resolving it, through their choice of interview segments, visuals, and commentary. As with other elements of the framework, especially genre, their experience reinforced the notion of the constructed nature of media messages.

On April 3, the students started planning their first narration. Tiseo reminded them that they were writing to be heard, not to be read. The students practiced reading the text out loud—adjusting it each time they stumbled across uncomfortable sentences. In subsequent discussion with the students, Tiseo explained that the opening narration should always go from the general to the specific to draw the audience into the story. He said, “How can we introduce the idea of the whole piece, but also introduce what J. is going to talk about?” Selena suggested beginning with an open question like, “What is rape?” Angel answered, “I like hitting them over the head with it more. We should start with hard facts. Later, we can come in with, `what is rape.’“ The girls finally decided to start with a modified hard sell, which, Angel explained, “ went well under the attack visuals that the audience was seeing.” In their opening narration, the students gave the audience general information about rape and then focussed on J. Under synthesizer music, we hear:

In recent years, sexual assault on women has become the fastest growing crime in North America. It is more common than heart attacks and alcoholism. One in every four women will become a victim of sexual assault. One in every two women will experience some type of unwanted sexual activity before the age of 21. In September, 1993, J.W. became part of the statistics. (V.T. Intro. V/O, Rape, the Ultimate Violation.)

The students created other narrations as they were needed during the editing sessions. Tiseo felt that this helped them write in a less wooden way. The students also knew where they needed to lead the audience for the next segment of interviews - and in a certain number of seconds. For their second narration, the group created a segue between J.’s state of mind after the rape and her explanation for not wanting to fight back. Selena told the group that they needed to justify, during their narration, why J. refused to fight. They could begin with descriptions of how other girls acted during the attack, and use visuals of different groups of girls sitting outside of school. The visual and the narration would stress that people react differently in difficult situations like this. They could then move back to J.’s experience. The students finally wrote:

Not all women react to being attacked in the same way; some choose to fight; others submit to their attackers. Experts believe that it is better to submit in order to avoid serious injury or even death. J. chose not to fight her attacker and survived her ordeal. (Script, Rape, the Ultimate Violation.)

The students built other voice-over segments similarly. They used them to present more general information and statistics on rape and to lead the audience to the next segment of the program.

The writing of the narration was not problem-free. Students were working under time pressure and peer pressure. Throughout the process, Angel and Selena disagreed on the tone the narration should take. Angel wanted to create the factual feeling of a news report, and include statistics and expert comments wherever possible. Selena had a more dilemma-oriented approach. In the narration, she would have liked to raise questions that the audience could answer when they watched J.’s testimony. The disagreement between the two girls came to a head on May 3:

On tape: I would have gone to court if I could have, but nothing came of it.

Selena: This is where I want to start. This is where it makes the most sense. We could say, “After all, the question rises, should women report the rapes and risk embarrassment.” J. said nothing came of it. It’s almost as if she’s answering the narration!

Tiseo: Well, that’s the purpose.

Angel: I don’t like it. It doesn’t make sense, because it doesn’t say the story. J. doesn’t say what happens. She just says nothing came of it. And then what? You rewind the whole thing and edit the earlier part in? It doesn’t work.

Selena: You don’t like the narrator asking a question?

Angel: I have nothing against the narration. But I’d rather we put in the point about the cops getting fingerprints, and also that she did the best she could but nothing came of it. Nothing came of what? We know that she got her apartment fingerprinted. The audience won’t know what she is talking about.

Selena: The audience will know as long as you bring in the lead-in.

(FN, May 03)

Although they initially thought that they would end their story with police reports and statistics on rape, the editing group decided that this would leave the audience with the message that J. had been broken by the event. Instead, they focussed on how she got her life back together:

Though it is difficult to recover from an ordeal such as rape, J. has made substantial progress in putting the ordeal behind her. She has accomplished this by attempting to have healthy experiences with men and getting on with her life. (V/O from Rape, the Ultimate Violation script.)

Because of Angel’s and Selena’s strong personalities, it was not always easy for them to agree on a direction. However, their understanding of how to shape and write narrations had advanced from their initial efforts. They now knew that through their narrations, they could lead the audience. They learned to write the information they wanted the audience to have into 10 to 30 second bytes and to make it flow. Their narration was the glue that kept the different pieces of the story together; they were the creators of the story.

Quinn and McMahon (1994), and Williamson (1981) argue that it is not easy for high school students to examine their own value systems and see them as anything but the way things are. Teaching ideology at the school level is difficult because the only culture the students know is the one they inhabit. We found this to be true with the group of students we studied. The ideologies of individual students were woven into their choice of interview questions, the subjects they chose to interview, and how they planned to edit their piece. However, they were not aware that their production decisions were driven by their own ideologies or personal values. This may have been, as Quinn and McMahon suggest, because they were too young to metacognitively evaluate their actions. Coming to terms with a concept like ideology takes a certain maturity. While most teenagers may be aware of the different values held by others, and while they may recognize that the differences are shaped by different cultural, racial, gendered, and class values and experiences, it is difficult for them to recognize that their judgments of the differences are the outcome of their own ideological stances.

Buckingham (1998) argues that analysis or deconstruction alone will not change students’ attitudes. Ideology in the media risks becoming what other people think unless it is related to students’ own experience and sense of identity. The three girls in the group had an emotional connection to the project, because, as Angel stated, rape was something that could happen to them. J., the rape victim, had not been much older than they were when she had been raped. Angel, Gia, Selena, and the girls who visited from other production groups during editing sessions, discussed their fear of being raped as they edited J.’s story together. Angel told the girls on three separate occasions that she had a dream where the same thing happened to her: “I felt like someone was on top of me and I couldn’t push them off. I was shivering when I woke up.” When Michele spoke to Selena about her involvement in the project, she said:

Rape, personally...I don’t know how to say this. But rape has really affected me. It’s a topic that I’m really sensitive to. I think girls are more sensitive to it. I guess for a man it’s harder to understand that. A man wouldn’t quite understand because if you can’t experience something, if you don’t have the sensitivity to experience it, you can’t... wouldn’t understand. Not that it could never happen to a man, but it’s so rare. It’s kind of unnatural for a man. I don’t mean to sound corny or stereotypical, but it is true. So we’re maybe more involved for that reason (Interview transcript, May 3, 1996).

It was difficult to determine to what extent the boys were affected by the project. As far as we were able to determine, rape was not part of their experience. During a brainstorming session Feb. 11, Rock told Tiseo that they wanted to do the video so “people could see how it was from J.’s young eyes.” Dino added, “We want to let others know what could happen when you’re not careful.” His message did not seem to be intended for those who rape, but for the potential victims who needed to keep themselves out of danger. For Dino, the project was about what happens to other people, since he could not see himself as either a victim or a rapist. However, one could interpret from the last phrase of his statement - “... what could happen when you’re not careful.”- the all-too-prevalent ideology of the female as careless cause of the rape act.

Although the other boys in the group were not as verbal about their inability to connect with the project, it did not touch on something that they identified with. Perhaps, as Williamson (1981) argues, if the boys had chosen a subject that concerned them personally, they might have had more interest and involvement the project. And yet, the boys initially promoted the topic of rape. It was Rock`s proposal. Tiseo recalls there being some typical titillating and almost vulgarly derisory talk among the boys about the subject during early discussion and planning - it was almost as if here was something to talk about that, given their milieu, was a taboo subject. This challenging of authority by being outrageous or choosing “forbidden” topics is characteristic of adolescent groups when given the opportunity to substantively and substantially express themselves in formal educational settings - especially those which feature modes of classroom instruction that habitually allow for little student active participation. It is possible, in this case, that the boys were caught off guard when the girls in the group decided to go along with the choice, and found themselves with a topic about which they had little relevant knowledge and, beyond its initially titillating aspects, no real personal commitment to. Not wanting to recant, they went along with the momentum that had been generated, but with less enthusiasm.

Although the students had written the questions, filmed the interviews, during the production, they were too involved, initially, in their roles on the team to concentrate on their own responses to J.’s and her father’s descriptions of the events. Watching the interview tapes for the first time, group members resumed their role as audience members, one they knew well and were comfortable with. They talked back to the television monitor. They were angry at what happened to J. They asked questions that were sometimes answered later in the interview. They commented on how calm she seemed about the whole thing. The group reacted similarly when they viewed the father’s interview. To continue the production process, they had to wear two hats; audience member who felt strongly about certain segments; and member of the production team who watched the footage with an eagle eye, to find ways it might fit together and tell a story, i.e. to `exploit’ other audiences.

Over 95% of the students at the School were from Italian backgrounds, and two-parent families. This seemed to colour how the students viewed the subject of their video as an audience, and also shaped the narrative of their documentary. During the reading of the interview questions, before the students knew much about J. or her father, Selena said, “This girl, doesn’t she have a mother? She must have been furious.” Angel said, “My father would’ve killed the guy.” Fred said, “Has anyone called the father of the rapist and said, `What’s wrong with your son?’“

The remarks reflect the positioning of the students as members of a community with strong images of mother and father and their respective and respecting roles. There appears to be some incredulity on the part of the students that parental response to the rape was apparently so muted. They speculate that their parents’ responses would have been more demonstrative and, in their minds, more supportive in the face of such a serious assault.

The valuing of parental involvement and support was also obvious in how the group secured the interview with the rape victim. Although J. was 19, the group approached her father for permission before contacting her. This may also have been because of their age. All of the people in the group were 16 or 17 and were still living at home. The students were surprised that J. was allowed to live alone so young. Most of their friends stayed with their families through the end of CEGEP (until they were at least 20). They knew they would need permission from their own parents to appear on a video like this, especially considering the subject matter.

The group decided that their documentary would be stronger if they included testimony from a parent. They wanted to know how J.’s parents reacted when they heard about the event and if they worried now about their daughter’s safety. They chose the father, because they felt that he would be more emotionally stable than the mother, who, said Dino, “... would surely fall apart.” We can see here the strongly gendered and ideological notion of emotional stability held by Dino and wonder about the extent to which it was shared by the other boys in the group and by the cultural community from which the students come. Indeed it seemed as if cultural values and gender may have played into the ways in which the students contributed to the successful completion of this project.

According to Tiseo, there is a difference in how boys and girls are raised in Italian families. Girls are given responsibility at a young age, asked to help with the housework or to baby-sit younger siblings. Boys are often spoiled, especially by their grandmothers. This difference manifests itself in Media Education classes that require students to be more self-directed. The most organized and successful groups that he has taught have had female directors and assistant directors, because, according to Tiseo, boys at this age are often less apt to accept responsibility than girls.

The difference in involvement became more apparent as the production process moved along. Although the boys were initially the leaders of the group, vital in setting up initial interview questions, meeting with the father to concretize his and his daughter’s involvement in the project, as the project moved along, they became less involved. This may have been because the project was long and drawn out. Selena told Michele, “boys often start off giving a lot of energy, but lose interest when they can’t see the end in sight.”

It is also possible that the boys found the subject matter difficult to work with, and had to search hard to find role models within it. Wall (1991) writes that since most books used in schools have central male characters, boys are used to `looking in a mirror,’ when they read books or work on projects in school. Here, they were locked on the outside; neither feeling any particular connection to rape as a subject, nor being able to put themselves into J.’s shoes.

When girls read literature in school, writes Wall, they often have the feeling of looking through a window at a life that they cannot relate to. In the instance of this video, the opposite was true. Here, they were looking in a mirror, and were in a comfortable and privileged place. The girls identified with J. She was a few years older than they were and, said Gia, “She seemed so strong after such an awful event.” When Angel, Selena, Gia and Rock worked on the interview tapes, on March 22, girls from the other production group were often at the control room door to watch, curious. The editing team was asked: “What school did this girl go to?” “Was she living on her own?” “Where was she living at the time?” Downtown?” “Remind me never to get an apartment in that neighbourhood!” Is she bitter about it now?” “Who could have done such a horrible thing?” As they listened to J. explain the rape over and over on tape, Gia said how angry all of this made her. Angel, Selena and the girls at the door agreed that they were all “... freaked out by the interview.”

The boys became somewhat more animated, however, when they watched the father’s interview. When J.’s father said that he paced in his living room, because he was so angry, Fred said, “I like that.” When the father mentioned that he wasn’t worried about his daughter because rape was one of those things you can’t control, Fred said, “We shouldn’t include that. We need to use things that show he’s a father. We want him to react to her reaction - but as a father.” They wanted J.’s father to act as a father was expected to act; as they imagined their fathers might act in the same situation. Tiseo said, “I agree with you. He’s going to appear juxtaposed with the daughter.” Later on in the interview, the father said, “If I ever get my hands on the rapist, I would kill him.” Fred and Rock said, “Now that is good!” They copied down the time code. Fred mentioned to Tiseo, “The father sometimes noticed me and Rock and looked at us.” Tiseo said, “He only did it noticeably at the end.” Rock said, “He did it a lot.” Rock and Fred needed to identify or feel a certain connection to one of the project’s protagonists. The father’s eye contact was taken as a small sign of complicity. Beyond this brief excitement, however, the boys seemed to become less involved in the project as it neared completion.

The identification with J. may have contributed to the girls’ expenditure of energy in finishing the project. Although they had secondary roles on the production team: lighting, set design and floor manager, Selena, Gia and Angel were back-seat directors all. They were also in charge of research and writing narrations, and were the editing team with the addition of Rock, the director. In fact, the taking over of control of the project may have been, as Tiseo suggests, because of their cultural identity, and the amount of responsibility they were given at home. It may also imitate the structure of Italian families: although the father was the head of the family in name, the mother ruled. But it was also due, in large part, to the fact that here was school work which gave the girls the sensation of “looking into the mirror.”

Before the rape group viewed their raw footage on March 23, Tiseo asked them to think about how they might juxtapose the father’s and daughter’s interviews. He suggested that as they watched the tapes, they write down the subject, tape and time code of the shots they wanted to keep, so they could find the shots later. The students viewed J.’s interview first, and jotted down sections that they liked. As they watched the father’s interview, Gia and Angel found several ties between the father’s and daughter’s versions of the story. On the tape, Angel asks the father how he felt when he heard the news. He answers that he was dumbfounded. Gia said, “She said it was hard to tell her parents, what did he say?” Angel answers, “When he realized what had happened, he was shocked.” Gia asks if they can put the two responses together. On the tape, the father talked about what happened when he heard about the event. He said that he walked around and around the living room. Gia said, “The girl went to the cops. He walked around the living room - what he did was paced.” Angel responds, “Her, she said that she accepted it, he was aggressive. For her, anger had nothing to do with it. The father said that he was more upset than the girl.” On the tape, Angel asks the father whether he found the whole thing psychologically painful. The three girls from the other group who are standing at the control room door try to find links between the two interviews as well. One said, “She talks about counselling too. You can tie them together.” Angel answers, “That has nothing to do with it.” Fred said, “That’s right, nothing.” Tiseo said, “This is good. The wheels are turning.”

In one sense, the students were actively reading the interview texts with a view to juxtaposing J.’s and her father’s viewpoints. Because they were producing their own text from the different pieces, they were especially concerned to find connections that supported their narrative intent. The connections were affirming of the dominant reading - the reading they were creating, the reading they expected the audience would make. That they had some positive reinforcement from the three onlookers hanging around the control room while they were editing the piece was also an affirmation of their (dominant) reading of the text.

But there was at least one point about which the reading of the onlookers and the producers were different - the suggestion made by one of the girls that they can use the “counselling” link and Angel and Fred’s emphatic response: “That has nothing to do with it”. In another sense, it could be argued that they were simultaneously attempting oppositional readings in order to test out the weaknesses of their texts in conveying the dominant message and rectify them, but we could see little direct evidence of this occurring in the discussions as a deliberately conscious activity.

There was some indication from the discussions we observed suggesting that the boys were negotiating their own readings of the narrative as it developed. In addition to being unable to identify with the principal protagonist of the text, they also had difficulty with the strength of character displayed by J. in the interview (and the text they ultimately produced). There were several instances leading up to the interviews where some of the boys voiced the opinion that by asking her some of the tough questions about the rape, J. would “...break down and cry.” The fact that she did not and the evolution of the text to reflect her strength may have contributed to the negotiated reading and the waning of involvement of the boys in the latter stages of production.

Because the rape documentary was completed on the last day of class, the group did not have the chance to see how the finished product impacted an outside audience. They seemed to think, however, that the subject would have an effect on their peers, because, according to Angel, the rape had happened to someone their age, “to a girl that could have been their friend.” As they edited their piece, the door to the control room was always crowded with girls from other groups. This informal audience response enabled them to consider how the documentary would explain more about rape to girls their age and show them that even when something terrible happens, “... it is possible to overcome it and move on, as J. has.”

The gun control group had more formal feedback from an outside audience. They were invited by Tiseo to talk about the production process and to show their video to an invited audience of school board officials. Donna, the director of the group said that when they heard the gun shot sound, the audience jumped. When the video was finished, the room was silent because, “...the audience was moved by the piece.” One of the school board commissioners told her, “I didn’t know people your age thought about such heavy subjects.” The group had similar reactions from peers who saw their commercial. One of their classmates said, “It gave me a real jolt. I didn’t really think they would have the kid use the gun.” Donna’s group was pleased that audience members were shocked by their commercial. “That is what we were trying to do; they got our message.” Her assistant director, Nadia, said, “Shocking people is the way that public service announcements get their messages across, because it helps people change. Maybe by seeing our commercial, they’ll realize how dangerous it can be to have guns in the home.” (FN)

Showing their public service announcement to an outside audience helped the group evaluate how effective their commercial was which made them even prouder of their work. Having media work seen by others is usually an integral part of Tiseo’s program. Videos are included in a media festival held at the end of the school year, where awards are distributed. Unfortunately, because of equipment failures that disrupted the production schedule, Tiseo and colleague Leon Llewellyn had decided not to hold the festival that year. Since there was no festival and because the rape documentary was finished on the last day of class, the students did not have the closure that most groups experience.

Grahame (1990) and Emery (1995, 1996) argue that producing media can give rise to students’ questions about media industries: the codes and practices, ownership and control, finance and distribution; legal constraints and the effects of technology. In the case of the rape documentary group, this was the least explored section of the framework. Since there was no need for a budget, the students did not have to deal with financial considerations. Tiseo would have liked to consider how they might distribute the project, but this was not possible since the students finished editing the last day of school. Their video has since been distributed to all of the moral religious education teachers in the school. Nor did the group have to wrestle with issues of control. Tiseo supported the project; and J., the rape victim, had no qualms about her entire story appearing in the video. Students did not have to struggle for ownership of their project either. Although Tiseo made suggestions for the shape of the piece, the group ultimately made decisions.

This became more obvious as the production moved along. The students dealt with legal constraints in terms of copyright, when they chose their musical sound track. Tiseo explained that they would not be able to use any published music unless they were able to get written permission from both the recording artist and the distributing company. He explained that, in the past, other students had produced terrific videos that could not be shown out of the department because they used copyrighted music. “Now everything we produce is copyright free,” he told them. They also had to create release forms, which they asked J., her father, and the students they interviewed to sign.

Grahame (1991) writes that even in a simulation concentrating on institution, few students were able to identify what the experience taught them. The student who commented on institution in her written evaluation, wrote, “I never realized how much work went on behind the scenes, how much preparation and time was spent before the actual filming. I never realized just how many people were involved in one program.” Several students in Tiseo’s group remarked on the endless pre-production tasks and compared them with how quickly the production shoot went. They were also surprised at how many people and roles it took to see a production from start to finish. Rock said, “It will change the way I look at television shows forever. It took us months to finish our video and it was only 7 minutes long. It must take years to finish full-length movies!”

Groups in other classes have dealt more extensively with institutions. The Hare Krishna wrestled with elements of ownership and control when they had to obtain written permission to shoot on location, and have the interview questions pre-approved by the temple leader. Other groups have had difficulty even finding a location, because their subject was so sensitive. A group who produced a documentary on gun control two years previously, could not find a gun store owner who would agree to be interviewed on camera or have his store shown.

Through the production of their video documentary on rape, the students developed a clear and sophisticated notion of the media text as a construction of reality. The students’ learning was most evident in their growth in understanding of genre. At the beginning, students saw documentaries and news stories as “the way things are.” After participating in the production process, they were able to see that documentaries were “constructed stories”. They demonstrated considerable technical knowledge and competence in their production of the video documentary and handled the narrative elements of the documentary genre with maturity and sensitivity.

Although the students engaged many of the theoretical concepts described by Dick’s conceptual framework, there were few specific formal explanations of theory during the production of their video. Grahame suggests that this is because the physical intensity of production work mitigates against explicit reference to theory. This was certainly true for the group of students we observed. In producing the rape video, students gave indications of a readiness to transfer their understanding about the constructed nature of the documentary to analyses of other texts in the same genre. The fact that the students worked until the last day of school to complete the video prevented the opportunity to reflect on its meaning.

Grahame (1991) writes that what production work tends to lack is opportunity for formal reflection during the process itself” (p. 379). She suggests that teachers introduce interim production meetings at various points to create space for reflection. While we observed considerable “reflection in action” (Schon, 1983) by students as they produced the video, we concur with Grahame’s observation.

In an interview with Tiseo several months after the study was finished, he told us that one of the things he felt was missing during the students’ production experience was the space to stop and think about what they were doing.” In the following year, he planned more time for production meetings and for student writing in individual production logs. He said, “This allows groups to account for where they are and raise questions about where they’re going.” The students’ logs could also be used to help students chart the growth in their understanding through the production process. There is considerable data here to suggest that these “follow-up” processes would be highly advantageous.

The students engaged many of the elements of Dick’s conceptual framework, providing them with the raw material for acquisition of what Vygotsky has referred to as “scientific concepts”. In only a few instances did the teacher specifically direct students’ attention to these concepts, and encourage them to reflect on them and to apply their reflection and understanding to critique not only other media texts of the same genre, but also their own. What appears necessary is that the production process itself be the object of reflection by the students; that critical questions be asked of the students in order to assist them in reflecting on the meanings of the experiences; and that teachers need to intervene by asking the students to connect the acts of production with “formal” concepts and compare their own experiences with them to other similar and professional productions. As Buckingham, Grahame and Sefton-Green (1995) discuss, the act of teacher intervention is problematic and is fraught with the potential to stage-manage “discovery”; however, our sense of the way in which the elements arose from the students’ activities and our observation of the egalitarian stance of the teacher of this group, especially in the production decision-making process, leads us to think that in the hands of a reflective, self-critical teacher, there is much more potential for student understanding of media education concepts in this kind of production-based approach than in the traditional teacher-centred and directed presentation/study.

As Grahame (1991) argues, and as Buckingham and Sefton-Green (1994, 1995) have already shown us, the potential outcomes of production work are multiple and diverse. The richness of the conversations of these students as they produced their documentary is ample evidence of her premise, and, we hope, adds to the growing body of evidence of the complexity of what students actually learn through production.

The authors greatly appreciate the assistance and participation of an outstanding media educator, Mr. Frank Tiseo. Without his pioneering work in teaching media, this study could have never been undertaken.

Argyris, C. (1982). Reasoning, Learning and Action. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass

Bazalgette, C. (1991). Media Education. London: Hodder and Stoughton Ltd.

Bazalgette (1995, July). How and when should media education be introduced? Paper presented to the first world meeting on the teaching of audiovisual media: La Coruna, Spain.

Bogdan R. & Biklen, S.K. (1992). Qualitative Research for education: An introduction to theory and methods. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Buckingham, D. (Ed.) (1998). Teaching popular culture: Beyond radical pedagogy. London: UCL Press.

Buckingham, D., Grahame, J., & Sefton Green, J., (1995) Making media: Practical production and media education. London: The English and Media Centre.

Buckingham, D. & Sefton Green, J. (1994). Cultural studies goes to school. Brighton: Falmer Press.

Buckingham, D. & Sefton Green, J., (1995). Making media: Practical production and media education.” The English and Media Magazine, 33, 8-13.

Cochran-Smith, M. & Lytle, S.L. (Eds.) (1993). Inside/outside: teacher research and knowledge. New York: Teachers’ College Press.

Dick, E. (1993). A media education model. In R. Shepherd, Elementary media education: The perfect curriculum. English Quarterly, 25(2-3), 35-38.

Emery, W.G. (1995, July). Beyond the technicist trap: Student production in media education. Workshop presented at the 4th International Congress on the Pedagogy of Representation, La Cornua, Spain.

Emery, W.G. (1996). Media literacy in Canada: current theory and classroom practices. In Petts, W.G. & Lawrence, D. Integrating visual and verbal literacies. Winnipeg, Manitoba: Inkshed Publications.

Glaser, B. & Strauss, A.L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine.

Grahame, J. (1990). Learning about media institutions through practical work. In M. Alvarado & O. Boyd-Barrett (Eds.), Media education, an introduction. London: British Film Institute.

Grahame, J. (1991). The English curriculum: Media. London: The English and Media Centre.

Grahame, J. (1992). The production process. In D. Buckingham (Ed.), Watching media learning. Brighton: Falmer Press.

Luchs, M. (1996) “I don’t like hearing Angel and not seeing her! Why did we do that?” An exploration of the teacher’s role in classroom video production and the students’ media learning in the process. Unpublished monograph submitted to the Department of Curriculum and Instruction, Faculty of Education (M.Ed.).

Masterman, L. (1985). Teaching the media. London: Comedia.

Quin, R. (1994, July). Teaching media: Paradigms for future instruction. Transcript of presentation given in Madison, Wisconsin.

Quin, R., & McMahon, B. (1991). Groundbreaking media literacy assessment from Australia. Mediacy, 17(3), 14-15.

Schon, D.A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Tiseo, F. & Llewellyn, L. (1996). Communication Arts mandate. In Laurier Macdonald High School educational report. Montreal: Jerome Le Royer School Board.

Wall, A. N. (1991). Gender-bias within literature in the high school English curriculum: The need for awareness, English Quarterly, 24, 2.

Williamson, J. (1981). How Girl 21 Handles Ideology. Screen Education, 38, 3.

1. This represents Quebec's nomenclature for the 5th year of secondary education. The students are about 17 years old.

2. The students have been given pseudonyms.

© Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology