Elena Chudaeva, George Brown College

Cynthia Blodgett, Athabasca University

Guilherme Loth, Crandall University

Thuvaragah Somaskantha, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre

The goal of this single-phase and convergent mixed methods study was to compare the differences in the effectiveness of the Community of Inquiry (CoI) presences of a community college blended block instructional model with the in-person counterpart. Data were gathered from the Community of Inquiry Survey, Blackboard LMS reports, and course evaluation surveys. The results indicate that students had a better overall experience with the blended course. The blended block model provided flexibility while achieving course goals. Further, findings reveal differences in all three CoI presences between the two course formats with more student awareness of the presences in the in-person course.

Keywords: blended learning; community college; community of inquiry; teaching presence; social presence; cognitive presence; mixed methods

L'objectif de cette étude utilisant des méthodes mixtes convergentes et en une seule phase était de comparer les différences dans l'efficacité des présences de la communauté d'enquête (CE) d'un modèle d'enseignement hybride en blocs d'un collège communautaire avec son homologue dans la modalité présentielle. Les données ont été recueillies à partir d’un sondage sur la communauté d'enquête, des rapports tirés du système de gestion de l’apprentissage Blackboard et des sondages d'évaluation des cours. Les résultats indiquent que les étudiants ont eu une meilleure expérience globale avec le cours hybride. Le modèle de blocs hybrides offrait de la flexibilité tout en atteignant les objectifs du cours. De plus, les résultats révèlent des différences dans les trois présences de la CE entre les deux modalités de cours, les étudiants étant plus conscients des présences dans le cours en présentiel.

Mots-clés: apprentissage hybride ; collège communautaire ; communauté d'enquête; présence pédagogique ; présence sociale ; présence cognitive; méthodes mixtes

Evidence suggests that blended learning provides more satisfaction and engagement (Taliaferro & Harger, 2022; Vaughan et al., 2013), results in similar examination scores to in-person courses (Jafar & Sitther, 2021; Shand et al., 2016), and positively impacts students’ performance (Broadbent, 2017; Vo et al., 2017). Cleveland-Innes and Wilton (2018) identified several key benefits of blended learning, including increased learning skills, greater access to information, improved satisfaction and learning outcomes, and opportunities to learn with and teach others.

Brown (1992) argued that research should be undertaken in real classrooms with real students and teachers. Research has shifted to explore blended learning, outcomes, teacher factors, and Community of Inquiry (Yin & Yuan, 2022). While blended learning is appealing because it can encompass the best of both distance and in-person education (McKenna et al., 2020; Rovai & Jordan, 2004; Young, 2002), blended learning can potentially mix the least effective elements of both in-person and technology-mediated learning. The challenge is effectively combining both instructional designs with matching learners’ characteristics and abilities (Drachsler & Kirschner, 2012; Garrison & Kanuka, 2004; Garrison & Vaughan, 2008).

This study systematically explored blended and in-person instructional models with the CoI teaching, cognitive, and social presences (Garrison, 2007) to support meaningful approaches to online teaching and learning (Vaughan et al., 2013). It adds to the body of mixed methods research in distance education, the least used approach, according to Bozkurt et al. (2015).

Blended learning is “a thoughtful integration of classroom face-to-face learning ... with online experiences” (Garrison & Kanuka, 2004, p. 3). Bonk and Graham (2005) described blended learning systems as a combination of in-person and computer-mediated instruction for the same students studying the same content in the same course. Horn and Staker (2011) defined blended learning as “any time a student learns at least in part in a supervised brick-and-mortar location away from home and at least in part through online delivery with some element of student control over time, place, path, [and] pace” (p. 3).

Beyond definition, the design of blended learning instruction must be one that reflects the particular educational setting in order for it to be successful. Educational institutions have adopted various blended designs. O’Connell (2016) as cited in Cleveland-Innes & Wilton (2018) offered seven configurations:

Cleveland-Innes and Wilton (2018) discussed several blended learning models for higher education:

Finally, in the HyFlex and Here or There (HOT) models, both on-site and remote students can attend learning activities in real-time (Raes et al., 2020; Zydney et al., 2019).

The effectiveness of blended learning, as identified in scholarly literature, includes student grades, satisfaction, flexibility, and retention. Studies found that final grades are similar in blended designs and in-person courses (Groen et al., 2020; Melton et al., 2009; Smith, 2013). Owston et al. (2013) reported that students with higher grade point averages prefer online courses and performed equally well with content acquisition, regardless of the mode of delivery (Cavanaugh & Jacquemin, 2015; Smith, 2013; Tang & Byrne, 2007).

Students report higher satisfaction in blended courses (Larson & Sung, 2009; Taliaferro & Harger, 2022; Tseng & Walsh, 2015), which may be mediated by advanced course design (Patwardhan et al., 2020). Learner-content interaction is the most important predictor of satisfaction, considering that all three kinds of interaction (learner-learner, learner-instructor, and learner-content) positively affect learning (Kuo et al., 2009).

Higher perceptions of a learning community may result in more satisfaction with blended than in-person courses (Daigle & Stuvland, 2021). Students report that the opportunity to interact with other learners beyond the physical classroom is a positive feature of the blended approach (Cornelius et al., 2019).

In addition, students’ personalities, age, and attitudes are vital factors in blended designs (Broadbent & Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, 2018; Kintu et al., 2017). Students prefer the flexibility of blended learning and faculty recognize the potential of blended learning to increase teacher-student interaction but acknowledge the need for more support in course redesign and training (Taylor et al., 2018). Student retention appears to be greater in blended as opposed to traditional courses (Groen et al., 2020).

Developed by Garrison et al. (2000), the CoI has been one of the most extensively used frameworks to guide instruction and research in online education (Bozkurt et al., 2015; Castellanos-Reyes, 2020; Kim & Gurvitch, 2020; Martin et al., 2022; Stenbom, 2018). The CoI includes three components: teaching presence, social presence, and cognitive presence. Teaching presence is the design, facilitation, and direction of cognitive and social processes to realize personally meaningful and educationally worthwhile learning outcomes (Anderson et al., 2001). Social presence is “the ability of participants to identify with the community, communicate purposefully in a trusting environment, and develop inter-personal relationships by way of projecting their individual personalities” (Garrison, 2017, p. 25). Cognitive presence is the extent to which learners can construct and confirm meaning through sustained reflection and discourse (Garrison et al., 2001).

The CoI framework influences online teaching internationally. Arsenijevic et al. (2022) found differences in all three presences among six countries (Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Slovenia, Romania, and Russia) during the COVID-19 pandemic, concluding that results depend on the educational context. Parrish et al. (2021) used the CoI to test a team-based approach to online learning with synchronous sessions in the USA. In Norway, Krzyszkowska and Mavrommati (2020) used the CoI model to recommend improving online learning designs to promote learning in the community. In the United Arab Emirates, Meda and ElSayary (2021) explored ways to establish all three presences during emergency remote teaching.

The CoI survey (Community of Inquiry, n.d.), validated by Swan et al. (2008), examines learning experiences and compares different learning contexts (Redstone et al., 2018; Stenbom, 2018).

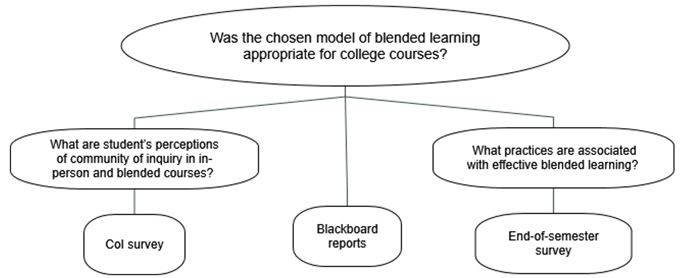

This single-phase convergent mixed methods study aimed to compare the influence of the CoI in two community college courses: a blended block model and an in-person course. Convergent mixed methods design is a one-phase design where both qualitative and quantitative data are collected and analyzed within the same timeframe (Creswell & Creswell, 2017). Three research questions guided the study design and analysis:

Qualitative and quantitative data were collected in parallel, analyzed separately, and merged. Quantitative data described students’ perceptions of all three presences in the CoI framework. Open-ended data supplied different perspectives on course design features. Blackboard Learn 9.1 Analytics provided additional insights into learners’ activity.

The instructor was also the primary investigator in the study; therefore, a student researcher collected data to avoid a perception of possible conflict of interest. The community college Research Ethics Board approved all measurement instruments used in the study.

The study participants were a convenience sample of Canadian community college students enrolled in an elective physics course in Fall 2019 (Table 1).

Table 1

Characteristics of Study Participants

| Total number of students | Gender | Program | |||

| Female | Male | Post-graduate certificate | Diploma | Advanced diploma | |

| 84 | 11 | 73 | 11 | 39 | 34 |

For most students, this was their first exposure to blended learning. The registration system did not mention the mode of delivery of the two courses, so students did not register for sections based on their preferred blended or in-person course delivery. The same instructor taught both the in-person and blended courses. Assessments were the same for both courses.

The blended block model (Cleveland-Innes & Wilton, 2018) was used to redesign the current in-person course, so the content was the same for both courses. The in-person sessions for the blended course were every other week, starting in week 1. During in-person sessions, students were introduced to a new topic and practiced new concepts individually and in small groups. During distance weeks, students investigated online modules which included readings, videos, quizzes, simulations, self-assessment activities, and online asynchronous discussion forums on the Blackboard LMS.

Inclusive course design with accessible content and appropriate technology promotes widely known principles of good practice in education (Chickering & Gamson, 1987). Consultation with an instructional designer and Universal Design for Learning coach was integral to the whole study, considering the unique needs of community college learners.

To answer research questions, three data collection processes were used (Figure 1):

The research team administered the CoI survey and end-of-semester survey at the end of the semester. Twenty-eight anonymous students in the in-person class and 24 in the blended section completed all surveys, yielding a response rate of 62%. Blackboard reports were generated in the middle and end of the semester to gain additional insights into students’ activity and behaviour online.

Figure 1

Research Questions and Data Collection Methods

First, CoI survey data were organized in a spreadsheet for further analysis. Descriptive statistics calculated the mean and standard deviation for each CoI survey item. Also, a hypothesis test produced summative values for each CoI presence. Second, the end-of-semester survey open-ended data analysis included a word count (Leech & Onwuegbuzie, 2007), content analysis for common themes, and word cloud visualization (McNaught & Lam, 2010). The word count function in Microsoft Word calculated the total number of words in each response group. Even though word count can decontextualize a word to a point where it is not understandable (Leech & Onwuegbuzie, 2007), we believe that word frequency provides a good indication of meaningfulness because most of the responses were in the form of a short phrase.

A text visualization content analysis of the overall text (Bhowmick, 2006) compared the two sets of textual data. The iterative process of revisiting data to ensure accuracy strengthened authenticity and validity. Textual data for both courses were coded for common themes. The qualitative textual data were uploaded to NVivo (Version 12, Lumivero, 2022) to generate word clouds. Words from the same families (e.g., experiment and experiments) were considered one word. Tables with word frequencies generated by NVivo were analyzed to get the usage rate of each word. Usage rate is word frequency divided by the total number of words (Leech & Onwuegbuzie, 2007).

Summarized respondents’ ratings for the three presences were calculated (Table 2). Mean responses for the 34 items ranged from 3.39 (item 16, blended section) to 4.82 (item 6, in-person section); standard deviations were highest for item 22 (SD = 1.28; blended section) and lowest for item 6 (SD = 0.40; in-person section). Mean ratings across the three presences exceeded 4.0 (on a 5-point scale) and presented general agreement that CoI was evident in an in-person class. In the blended section, the mean exceeded 4.0 for teaching and cognitive presences but not for social presence. A two-tailed two-sample t -test with alpha set to 0.05 confirmed a significant difference between in-person and blended classes for social presence.

Table 2

Descriptive Statistics for CoI Presences

| CoI presence | In-person1 | Blended2 | p-value | ||

| M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Teaching | 4.57 | 0.46 | 4.53 | 0.49 | 0.765 |

| Social | 4.20 | 0.64 | 3.58 | 0.72 | 0.002 |

| Cognitive | 4.33 | 0.68 | 4.03 | 0.67 | 0.116 |

Note. 1N = 28; 2N = 24.

Survey results are shown in the Appendix. Examination provides a more detailed picture of learners’ perspectives. Teaching presence was strongly felt via course design, organization, and facilitation. Even though all ratings were higher than 4.0, items related to developing a sense of community and providing feedback were among those with the lowest rating, indicating less agreement about the degree to which this behaviour was present. However, items related to feedback were rated higher in the blended section.

The survey results for social presence yielded some interesting differences between the two types of course delivery. Affective expression items rated above 4.0 for the in-person sections. However, only about half the students surveyed perceived web-based communication as a suitable medium for interaction. Open communication was perceived as successful when interacting with other students (M > 4.0) but not online, including in online discussions (in the blended class, the mean was about 3.9). Learners in both courses felt that they could “disagree with other participants” and “their point of view was acknowledged” (M > 4.0).

Data for cognitive presence items shows unanimous agreement that this presence was present in the in-person course (M > 4.0 for all items). Students in the blended section had mixed feelings: “problem posed” did not always create interest and motivation to explore further, but course activities “piqued curiosity.” In the blended section, students felt strongly about the integration phase (M > 4.0 for all items); however, they were less sure that they had developed solutions applicable in practice (M = 3.96). Also, blended learners felt that “online discussions were valuable” in helping them “appreciate different perspectives” (M = 4.04).

There were six questions in the survey, four of which were open ended. Data indicated that meaningful inclusion of technology has learning value for college students and helps increase engagement with course materials.

When asked about overall learning experience (Table 3), answers revealed a higher rating for the blended section. Additionally, final grades were slightly different in both courses (Table 4).

Table 3

Means and Standard Deviations of the Overall Learning Experience

| In-person | Blended | ||

| M | SD | M | SD |

| 4.43 | 1.00 | 4.50 | 0.70 |

Table 4

Means and Standard Deviations of Final Grades on a 100% Scale

| In-person | Blended | ||||

| M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range |

| 92.3 | 6.00 | 31.7 | 89.4 | 10.2 | 51.9 |

Next, findings for the four open-ended questions are presented. As shown in Table 5, the number of words in responses varied for each open-ended question. Tables 6, 7, 8, and 9 further analyze these eight sets of textual data. It is worth mentioning that in word clouds, the size of words can be used to compare ideas in one image only. Tables with usage rates are provided to assist with comparing two sets of data.

Table 5

Number of Words in Student Responses to Open-Ended Survey Questions

| Question | Number of words | |

| In-person | Blended | |

| 2 | 107 | 69 |

| 3 | 98 | 45 |

| 4 | 145 | 84 |

| 5 | 85 | 51 |

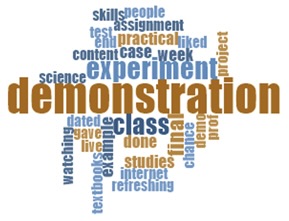

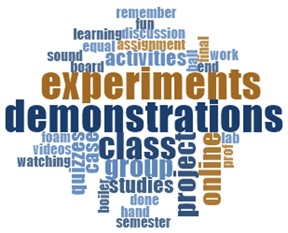

When asked what activity they liked the most, students in both courses most often mentioned demonstrations and experiments (Table 6). However, in the in-person section, students mentioned these activities twice as often. Various in-class activities were also among their favourite activities. Also, students reported watching other people doing experiments as fun and educational.

Table 6

Frequency of Word Use in Response to the Question: Which Activity Did You Like the Most?

| In-person | Blended | ||

| Word clouds | |||

|  | ||

| Usage rate of most popular words | |||

| Word | Usage (%) | Word | Usage (%) |

| Demonstrations | 16 | Demonstrations | 7 |

| Experiment | 7 | Experiments | 7 |

| Class | 7 | Class | 6 |

| Project | 5 | Group | 4 |

| Case studies | 2 | Project | 4 |

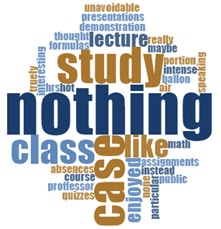

Table 7 presents responses to question 3 which concerned the least liked class activity. Interestingly, the answer “nothing” appears in both sets but more frequently in the in-person section. In the blended class, online activities (“online” and “discussions”) were the most frequent responses.

Table 7

Frequency of Word Use in Response to the Question: Which Activity Did You Like the Least?

| In-person | Blended | ||

| Word clouds | |||

|  | ||

| Usage rate of most popular words | |||

| Word | Usage (%) | Word | Usage (%) |

| Nothing | 7 | Online | 13 |

| Case | 5 | Discussions | 11 |

| Study | 5 | Material | 5 |

| Class | 4 | Case study | 2 |

| Enjoyed | 2 | Quizzes | 2 |

| Math | 1 | Nothing | 2 |

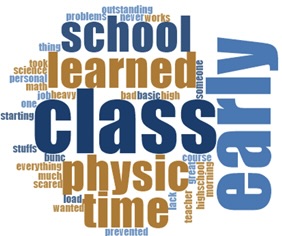

This question asked students what supported their learning of the course material (Table 8). In addition to in-class related activities (e.g., “class”, “demonstration”, and “lecture”), students in the in-person section mentioned “google” and “teacher” being supportive of their learning. Students in the blended class appreciated material designed for distance classes.

Table 8

Frequency of Word Use in Response to the Question: What Helped You Learn the Course Material?

| In-person | Blended | ||

| Word clouds | |||

|  | ||

| Usage rate of most popular words | |||

| Word | Usage (%) | Word | Usage (%) |

| Class | 4 | Online | 6 |

| Case | 2 | Material | 5 |

| Demonstrations | 2 | Class | 4 |

| Lectures | 2 | Reading | 4 |

| Studies | 2 | Demonstration | 2 |

| Experiments | 1 | Teacher | 2 |

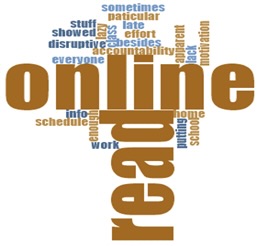

College students are diverse in background, prior knowledge, and personal and job situations. In addition, due to the nature of general education courses, students have different course loads. As shown in Table 9, answers to a question about what prevented the participants from learning varied from the timetable and work-related issues to course design features. It is worth noting that students in the in-person class mentioned “personal problems”, and “motivation” was mentioned in the blended section.

Table 9

Frequency of Word Use in Response to the Question: What Prevented You from Learning?

| In-person | Blended | ||

| Word clouds | |||

|  | ||

| Usage rate of most popular words | |||

| Word | Usage (%) | Word | Usage (%) |

| Early | 4 | Online | 4 |

| Class | 4 | Read | 4 |

| School | 2 | Lack | 2 |

| Time | 2 | Lazy | 2 |

| Personal problems | 2 | Motivation | 2 |

Note. The most frequent answer in both sections, “nothing” (12% of the total number of words) was removed from the analysis.

In an analysis of survey data concerning the instructor, it was found that students appreciated material posted on Blackboard, in-class handouts, in-class activities, and good facilitation of classes (Table 10).

Table 10

Instructional Activities That Supported Learning

| Instructional activity | Percentage of students mentioning the activity | |

| In-person | Blended | |

| In-person sessions | 61 | 30 |

| Materials on Blackboard | 25 | 73 |

| Students’ demonstrations | 64 | 33 |

| Instructor’s demonstrations | 29 | 42 |

The survey also asked students how much time they spent on online activities each week. Considering that the standard weekly class is three hours, students in the blended course spent less time studying during distance weeks than students in the in-person class. Also, a couple of students in the in-person class suggested reducing class time to two hours. Lastly, according to self-reported time, students spent less than 3 hours per week on activities on Blackboard (Table 11).

Table 11

Number of Hours Spent Each Week on Online Activities

| In-person | Blended | ||

| M | SD | M | SD |

| 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 0.5 |

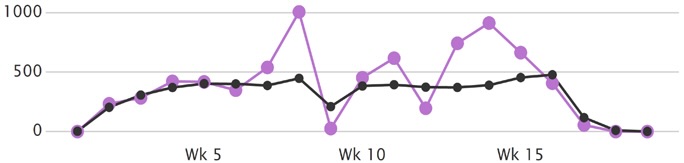

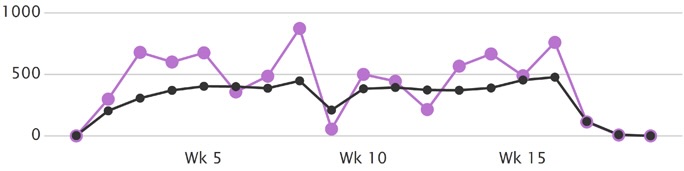

Reports reveal that the blended course had higher access, interaction, and minutes than the in-person course and department averages (Figures 2 and 3). Students in the blended class tended to access Blackboard regularly, whereas in the in-person class, access was mostly during assessment periods (weeks 9 and 14).

Figure 2

Minutes Spent on Blackboard Weekly: In-Person Course Students

Note. Wk = week.

Figure 3

Minutes Spent on Blackboard Weekly: Blended Course Students

Note. Wk = week.

Data confirm that students in the blended course accessed the content area more often and consistently. Students visited the area with assessment tasks most often. In the blended section, the number of hits was twice the number for the in-person section. Unexpectedly, user activity inside content areas decreased in the second half of the course (Table 12).

Table 12

Number of Hits Inside Content Area Per Course Period

| Course period | In-person | Blended |

| Weeks 1 to 7 | 1,285 | 1,334 |

| Weeks 8 to 15 | 981 | 889 |

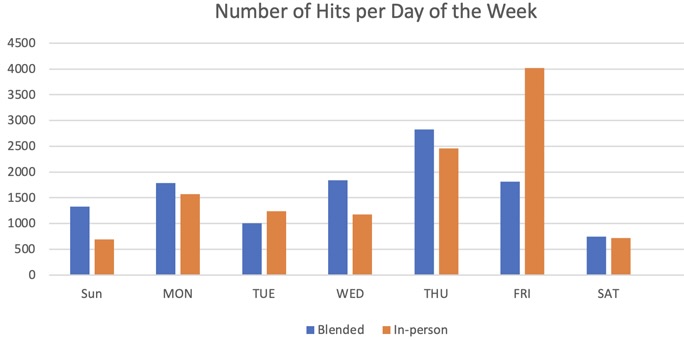

Students accessed the course most often on the day of the class: of all accesses per week, 46% for the in-person section were on Friday and 38% for the blended class were on Thursday. However, students in the blended class demonstrated more consistent activity throughout the week (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Daily Number of Hits on Blackboard: In-Person vs. Blended

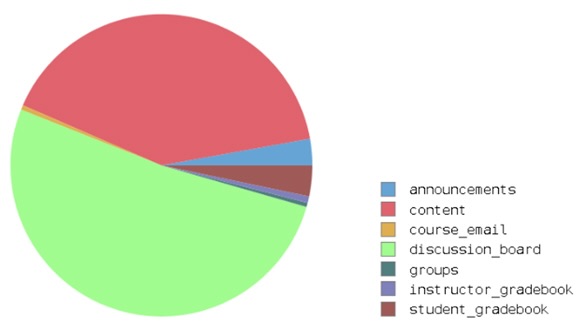

Blackboard reports also provided insight into assessing course design based on students’ online behaviour. Figure 5 illustrates that students in the blended course accessed online discussions more often than the content area. In the in-person section of the course, as might be expected, students most often accessed the course’s content area (posted learning materials); there were no discussion forums.

Figure 5

Frequency and Type of Content Accessed by Students in the Blended Course

Analysis of the CoI survey responses reveals that teaching presence had the highest rating for both courses. Teaching presence is key to establishing and sustaining a community of inquiry (Cornelius et al., 2019; Garrison et al., 2010; Redstone et al., 2018). The most favourite activity in both courses, demonstrations by the instructor and students, was a valuable contributor to the high rating of teaching presence. Access to course materials on demand has been helpful, especially around test times. Planning and organizing materials before and during the course support a strong teaching presence (Courduff et al., 2021; le Roux & Nagel, 2018).

Interestingly, students in the blended course placed greater value on the effectiveness of the instructor’s feedback. Online discussions allowed students to contribute meaningfully to the community of learners and instructors to respond promptly to correct misconceptions and direct further learning more effectively based on individual needs. However, facilitation of the overall learning process was rated higher in the in-person class. This may be showing the importance of teacher support in blended courses to keep students motivated to study online due to a wide range of self-regulated learning profiles (Broadbent & Fuller-Tyszkiewisz, 2018; Fryer & Bovee, 2018).

Social presence was significantly lower in the blended course than in the in-person course. A lower rating for social presence is consistent with other studies (Cornelius et al., 2019; Honig & Salmon, 2021; Lacaste et al., 2022; Stewart et al., 2021). Even though students in the blended section visited online discussions more often than the course materials and were comfortable interacting with other participants, they did not feel that they knew other course participants well. Unexpectedly, a sense of belonging was rated higher in the blended course. One possible explanation could be that online discussions positively affect identifying with the class community by allowing every student to contribute. A higher perception of social presence in the in-person class was anticipated because students were more familiar with in-person experiences and were first-time learners in a blended environment. Communication effectiveness in online environments is still an important area of inquiry (Kim & Gurvitch, 2020). Group cohesion was rated similarly for both courses. This shows that blended learning allows to build relationships due to the in-person component and online discussions even though students meet less often than in the in-person course. Since social presence has a connection to teaching and learning elements (Garrison et al., 2010), paying particular attention to connections between in-person and online components of blended learning may support the development of social presence.

Course design considered Meyer’s (2003) and Vaughan and Garrison’s (2005) suggestion that the triggering event and exploration phases were preferably done in person. Results reveal the difference between all cognitive presence categories and integration and resolution phases were more active in the in-person course whereas, in the blended course, only the integration phase was most active. Such a difference in the triggering event phase between the two classes was unexpected. The blended course was designed to introduce new concepts in the in-person weeks and then allow students to master them during online weeks. The explanation could be that in-person sessions in the blended course resulted in more cognitive load and faster exploration of new concepts, while distance weeks required more self-regulation. Also, students had mixed perceptions about activities during distance weeks in the blended course; some felt online materials and online discussions supported learning, and at the same time, online discussions were among the least favourite activities. Lower ratings for the cognitive presence in the blended course may be connected to the lower ratings for social presence, confirming that cognitive presence and social presence reinforce each other and have a two-way dynamic (Redstone et al., 2018).

Learner activity on Blackboard is an essential source of information about learning and course interactions that can shed light on course design features. In this case, reduced activity in the second half of the semester may be due to course design; less posted content and more assessment activities compared to the first half of the course.

Final grades demonstrate a wider range for the blended section. Adaptation to blended learning environments may be a factor as they are known to be required for students (Cleveland-Innes & Garrison, 2010). According to Blackboard reports, blended designs foster more significant interaction with course material and with peers, and the development of digital literacy. Consistent with Bates’ (2019) idea about teaching in a digital age and skills students should acquire, we can conclude that blended learning provides an opportunity to develop valuable digital, collaboration, and communication skills. Promoting self-regulated strategies in blended college courses would help students gain new skills required to be effective online learners (Wandler & Imbriale, 2017).

The convenience sample used for data collection and relatively small classes could be considered limitations. Future studies can overcome these limitations by exploring the benefits and challenges of blended learning using another sampling method. Also, replication of this study with another instructor teaching both in-person and blended courses in a different educational setting, but using the same model, may provide additional insights. Since there are many ways to create blended learning environments, this study provides some insights into the possible design of general education STEM courses.

Further, policymakers and practitioners need research-based information about the conditions and practices under which online and blended learning are effective. Additional research is required to explore the CoI framework as a tool for creating effective blended environments for community college learners with different motivation levels and ways of adapting to online/blended learning environments.

This study explored the blended block model for community college courses. Results indicate that this model was as effective as an in-person course in meeting learning outcomes with the benefits of flexibility for students. However, the findings should be generalized with caution due to variables such as a specific model for blended learning, students’ characteristics, the nature of instructional goals, and learning resources. One of the significant contributions of this research is the examination of the CoI framework in blended courses in a community college setting. In addition, we should not forget about skills that students need to develop for success in a digital age and in the VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous) world in which we live. Findings support that well-designed blended learning is an excellent opportunity to practice these skills in a safe environment for community college students. All in all, blended courses have the potential to create enhanced opportunities for teacher-student interaction, added flexibility in the teaching and learning environment, and opportunities for continuous improvement (Vaughan, 2007).

Anderson, T., Rourke, L., Garrison, D. R., & Archer, W. (2001). Assessing teacher presence in a computer conferencing context. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 5(2), 1-17.

Arbaugh, J. B., Cleveland-Innes, M., Diaz, S. R., Garrison, D. R., Ice, P., Richardson, J. C., & Swan, K. P. (2008). Developing a community of inquiry instrument: Testing a measure of the Community of Inquiry framework using a multi-institutional sample. Internet and Higher Education, 11, 133-136. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.457.2233&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Arsenijevic, J., Belousova, A., Tushnove, Y., Grosseck, G., & Živkov, A. M. (2022). The quality of online higher education teaching during the Covid-19 pandemic. International Journal of Cognitive Research in Science, Engineering & Education, 10(1), 47-55. https://doi.org/10.23947/2334-8496-2022-10-1-47-55

Bates, T. (2019). Teaching in a digital age (2nd ed.). Pressbooks. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/teachinginadigitalagev2/

Bhowmick, T. (2006). Building an exploratory visual analysis tool for qualitative researchers. In Proceedings of AutoCarto 2006. Cartography and Geographic Information Society. http://www.cartogis.org/docs/proceedings/2006/bhowmick.pdf

Bonk, C. J., & Graham, C. R. (2005). The handbook of blended learning: Global perspectives, local designs. Pfeiffer.

Bozkurt, A., Akgun-Ozbek, E., Yilmazel, S., Erdogdu, E., Ucar, H., Guler, E., Sezgin, S., Karadeniz, A., Sen-Ersoy, N., Goksel-Canbek, N., Dincer, G. D., Ari, S., & Aydin, C. H. (2015). Trends in distance education research: A content analysis of journals 2009-2013. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v16i1.1953

Broadbent, J. (2017). Comparing online and blended learner’s self-regulated learning strategies and academic performance. The Internet and Higher Education, 33, 24-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2017.01.004

Broadbent, J., & Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. (2018). Profiles in self-regulated learning and their correlates for online and blended learning students. Educational Technology Research & Development, 66(6), 1435-1455. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-018-9595-9

Brown, A. L. (1992). Design experiments: Theoretical and methodological challenges in creating complex interventions in classroom settings. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 2(2), 141-178. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls0202_2

Castellanos-Reyes, D. (2020). 20 years of the Community of Inquiry framework. TechTrends: Linking Research & Practice to Improve Learning, 64(4), 557-560. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-020-00491-7

Cavanaugh, J. K., & Jacquemin, S. J. (2015). A large sample comparison of grade-based student learning outcomes in online vs. face-to-face courses. Online Learning, 19(2). https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v19i2.454

Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven principles of good practice in undergraduate education. American Association for Higher Education Bulletin, 39(7), 2-6. https://aahea.org/articles/sevenprinciples1987.htm

Cleveland-Innes, M., & Garrison, D. R. (2010). The role of learner in an online community of inquiry: Instructor support for first-time online learners. In N. Karacapilidis (Ed.), Web-based learning solutions for communities of practice: Developing virtual environments for social and pedagogical advancement (pp. 167-184). Information Science Reference.

Cleveland-Innes, M., & Wilton, D. (2018). Guide to blended learning. Commonwealth of Learning. http://oasis.col.org/handle/11599/3095

Community of Inquiry. (n.d.). Community of Inquiry survey. https://coi.athabascau.ca/coi-model/coi-survey/

Cornelius, S., Calder, C., & Mtika, P. (2019). Understanding learner engagement on a blended course including a MOOC. Research in Learning Technology, 27, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.25304/rlt.v27.2097

Courduff, J., Lee, H., & Cannaday, J. (2021). The impact and interrelationship of teaching, cognitive, and social presence in face-to-face, blended, and online masters courses. Distance Learning, 18(1), 1-12.

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Sage publications.

Daigle, D. T., & Stuvland, A. (2021). Teaching political science research methods across delivery modalities: Comparing outcomes between face-to-face and distance-hybrid courses. Journal of Political Science Education, 17, 380-402. https://doi.org/10.1080/15512169.2020.1760105

Drachsler, H., & Kirschner, P. A. (2012). Learner characteristics. In Encyclopedia of the sciences of learning (pp. 1743-1745). Springer.

Fryer, L. K., & Bovee, H. N. (2018). Staying motivated to e-learn: Person- and variable-centred perspectives on the longitudinal risks and support. Computers & Education, 120, 227-240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.01.006

Garrison, D. R. (2007). Online community of inquiry review: Social, cognitive, and teaching presence issues. Online Learning Journal, 11(1), 61-72. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v11i1.1737

Garrison, D. R. (2017). E-learning in the 21st century: A community of inquiry framework for research and practice (3rd ed.). Routledge/Taylor and Francis.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2, 87−105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T, & Archer, W. (2001). Critical thinking, cognitive presence, and computer conferencing in distance education. American Journal of Distance Education, 15(1), 7-23. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923640109527071

Garrison, D. R., Cleveland-Innes, M., & Fung, T. S. (2010). Exploring causal relationships among teaching, cognitive and social presence: Student perceptions of the community of inquiry framework. The Internet and Higher Education, 13(1-2), 31-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2009.10.002

Garrison, D. R., & Kanuka, H. (2004). Blended learning: Uncovering its transformative potential in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 7(2), 95-105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2004.02.001

Garrison, D. R., & Vaughan, N. (2008). Blended learning in higher education: Framework, principles and guidelines. Jossey-Bass.

Groen, J., Ghani, S., Germain-Rutherford, A., & Taylor, M. (2020). Institutional adoption of blended learning: Analysis of an initiative in action. Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 11(3), Article 9. https://doi.org/10.5206/cjsotl-rcacea.2020.3.8288

Honig, C. A., & Salmon, D. (2021). Learner presence matters: A learner-centered exploration into the Community of Inquiry framework. Online Learning, 25(2), 95-119.

Horn, M. B., & Staker, H. (2011). The rise of K-12 blended learning. Innosight Institute, 5(1), 1-17. https://www.inacol.org/resource/the-rise-of-k-12-blended-learning/

Jafar, S., & Sitther, V. (2021). Comparison of student outcomes and evaluations in hybrid versus face-to-face anatomy and physiology I courses. Journal of College Science Teaching, 51(1), 58-66. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27133141

Kim, G., & Gurvitch, R. (2020). Online education research adopting the Community of Inquiry framework: A systematic review. Quest, 72(4), 395-409. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2020.1761843

Kintu, M. J., Zhu, C., & Kagambe, E. (2017). Blended learning effectiveness: The relationship between student characteristics, design features and outcomes. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 14, Article 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-017-0043-4

Krzyszkowska, K., & Mavrommati, M. (2020). Applying the Community of Inquiry e-learning model to improve the learning design of an online course for in-service teachers in Norway. Electronic Journal of E-Learning, 18(6), 462-475. https://doi.org/10.34190/JEL.18.6.001

Kuo, Y. C., Eastmond, J. N., Bennett, L. J., & Schroder, K. E. E. (2009). Student perceptions of interactions and course satisfaction in a blended learning environment. In G. Siemens & C. Fulford (Eds.), Proceedings of ED-MEDIA 2009—World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia & Telecommunications (pp. 4372-4380). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE).

Lacaste, A. V., Cheng, M.-M., & Chuang, H.-H. (2022). Blended and collaborative learning: Case of a multicultural graduate classroom in Taiwan. PLoS ONE, 17(4), Article e0267692. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0267692

Larson, D. K., & Sung, C.-H. (2009). Comparing student performance: Online versus blended versus face-to-face. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 13(1), 31-42.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0267692//doi.org/10.24059/olj.v13i1.1675

le Roux, I., & Nagel, L. (2018). Seeking the best blend for deep learning in a flipped classroom - Viewing student perceptions through the Community of Inquiry lens. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 15, Article 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-018-0098-x

Leech, N. L., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2007). An array of qualitative data analysis tools: A call for data analysis triangulation. School Psychology Quarterly, 22(4), 557-584. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2007-19518-005

Lumivero. (2022). NVivo (Version 12) [Computer software]. https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo/

Martin, F., Wu, T., Wan, L., & Xie, K. (2022). A meta-analysis on the Community of Inquiry presences and learning outcomes in online and blended learning environments. Online Learning, 26(1), 325-359. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v26i1.2604.

McKenna, K., Gupta, K., Kaiser, L., Lopes, T., & Zarestky, J. (2020). Blended learning: Balancing the best of both worlds for adult learners. Adult Learning, 31(4), 139-149. https://doi.org/10.1177/1045159519891997

McNaught, C., & Lam, P. (2010). Using Wordle as a supplementary research tool. Qualitative Report, 15, 630-643.

Meda, L., & ElSayary, A. (2021). Establishing social, cognitive and teacher presences during emergency remote teaching: Reflections of certified online instructors in the United Arab Emirates. Contemporary Educational Technology, 13(4), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.30935/cedtech/11073

Melton, B. F., Bland, H. W., & Chopak-Foss, J. (2009). Achievement and satisfaction in blended learning versus traditional general health course designs. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 3(1), Article 26. https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2009.030126

Meyer, K. (2003). Face-to-face versus threaded discussions: The role of time and higher-order thinking. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 7(3), 55-65.

Owston, R., York, D., & Murtha, S. (2013). Student perception and achievement in a university blended learning strategic initiative. Internet and Higher Education, 18, 38-46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2012.12.003

Parrish, C. W., Guffey, S. K., Williams, D. S., Estis, J. M., & Lewis, D. (2021). Fostering cognitive presence, social presence and teaching presence with integrated online-team-based learning. TechTrends: Linking Research & Practice to Improve Learning, 65, 473-484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-021-00598-5

Patwardhan, V., Rao, S., Thirugnanasambantham, & Prabhu, N. (2020). Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework and course design as predictors of satisfaction in emergency remote teaching: Perspectives of hospitality management students. Journal of E-Learning & Knowledge Society, 16(4), 94-103. https://doi.org/10.20368/1971-8829/1135315

Raes, A., Detienne, L., Windey, I., & Depaepe, F. (2020). A systematic literature review on synchronous hybrid learning: Gaps identified. Learning Environments Research, 23, 269-290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-019-09303-z

Redstone, A. E., Stefaniak, J. E., & Luo, T. (2018). Measuring presence: A review of research using the Community of Inquiry instrument. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 19(2), 27-36.

Rovai, A. P., & Jordan, H. (2004). Blended learning and sense of community: A comparative analysis with traditional and fully online graduate courses. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 5(2). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v5i2.192

Shand, K., Farrelly, S. G., & Costa, V. (2016). Principles of course redesign: A model for blended learning. In G. Chamblee & L. Langub (Eds.), Proceedings of 2016 Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference (pp. 378-389). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/172311/

Smith, N. V. (2013). Face-to-face vs. blended learning: Effects on secondary students’ perceptions and performance. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 89, 79-83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.08.813

Stenbom, S. (2018). A systematic review of the Community of Inquiry survey. The Internet and Higher Education, 39, 22-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2018.06.001

Stewart, M. K., Hilliard, L., Stillman-Webb, N., & Cunningham, J. M. (2021). The Community of Inquiry in writing studies survey: Interpreting social presence in disciplinary contexts. Online Learning, 25(2), 73-94.

Swan, K. P., Richardson, J. C., Ice, P., Garrison, D. R., Cleveland-Innes, M., & Arbaugh, J. B. (2008). Validating a measurement tool of presence in online communities of inquiry. E-Mentor, 24(2), 1-12. https://e-mentor.edu.pl/_xml/wydania/24/543.pdf

Taliaferro, S. L., & Harger, B. L. (2022). Comparison of student satisfaction, perceived learning and outcome performance: Blended instruction versus classroom instruction. Journal of Chiropractic Education, 36(1), 22-29. https://doi.org/10.7899/JCE-19-33

Tang, M., & Byrne, R. (2007). Regular versus online versus blended: A qualitative description of the advantages of the electronic modes and a quantitative evaluation. International Journal on E-Learning, 6(2), 257-266. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ754635

Taylor, M., Vaughan, N., Ghani, S. K., Atas, S., & Fairbrother, M. (2018). Looking back and looking forward: A glimpse of blended learning in higher education from 2007-2017. International Journal of Adult Vocational Education and Technology, 9(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJAVET.2018010101

Tseng, H. W., & Walsh, E. J., Jr. (2015). Blended vs. traditional course delivery: Comparing students’ motivation, learning outcomes, and preferences. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 17(1). https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Hung_Tseng2/publication/301204339_Blended_vs_Traditional_Course_Delivery_Comparing_Students'_Motivation_Learning_Outcomes_and_Preferences_Quarterly_Review_of_Distance_Education_171/links/57bdac2d08ae882481a51517.pdf

Vaughan, N. D. (2007). Perspectives on blended learning in higher education. International Journal on E-Learning, 6(1), 81-94. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/255567084_Perspectives_on_Blended_Learning_in_Higher_Education

Vaughan, N. D., Cleveland-Innes, M., & Garrison, D. R. (2013). Teaching in blended learning environments: Creating and sustaining communities of inquiry. Athabasca University Press.

Vaughan, N. D., & Garrison, D. R. (2005). Creating cognitive presence in a blended faculty development community. The Internet and Higher Education, 8(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2004.11.001

Vo, H. M., Zhu, C., & Diep, N. A. (2017). The effect of blended learning on student performance at course-level in higher education: A meta-analysis. Studies in Education Evaluation, 53, 17-28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2017.01.002

Wandler, J., & Imbriale, W. (2017). Promoting undergraduate student self-regulation in online learning environments. Online Learning 21(2). https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v21i2.881

Yin, B., & Yuan, C.-H. (2022). Detecting latent topics and trends in blended learning using LDA topic modeling. Education and Information Technologies, 27, 12689-12712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11118-0

Young, J. R. (2002, March 22). “Hybrid” teaching seeks to end the divide between traditional and online instruction. The Chronicle of Higher Education, A33.

Zydney, J. M., McKimmy, P., Lindberg, R., & Schmidt, M. (2019). Here or there instruction: Lessons learned in implementing innovative approaches to blended synchronous learning. TechTrends, 63, 123-132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-018-0344-z

| Indicator | In-person | Blended | ||||||||||||

| M | SD | % | M | SD | % | |||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

| TEACHING PRESENCE | ||||||||||||||

| Design & Organization | ||||||||||||||

| 1. The instructor clearly communicated important course topics. | 4.61 | 0.96 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 21 | 70 | 4.58 | 0.72 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 29 | 67 |

| 2. The instructor clearly communicated important course goals. | 4.61 | 0.57 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 32 | 64 | 4.54 | 0.59 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 38 | 58 |

| 3. The instructor provided clear instructions on how to participate in course learning activities. | 4.64 | 0.68 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 25 | 71 | 4.71 | 0.55 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 21 | 75 |

| 4. The instructor clearly communicated important due dates/time frames for learning activities. | 4.79 | 0.42 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 79 | 4.71 | 0.55 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 21 | 75 |

| Facilitation | ||||||||||||||

| 5. The instructor was helpful in identifying areas of agreement and disagreement on course topics that helped me to learn. | 4.68 | 0.55 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 71 | 4.62 | 0.78 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 25 | 58 |

| 6. The instructor was helpful in guiding the class towards understanding course topics in a way that helped me clarify my thinking. | 4.82 | 0.40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18a | 81a | 4.50 | 0.66 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 33 | 58 |

| 7. The instructor helped to keep course participants engaged and participating in productive dialogue. | 4.57 | 0.74 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 25 | 68 | 4.54 | 0.59 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 38 | 58 |

| 8. The instructor helped keep the course participants on task in a way that helped me to learn. | 4.61 | 0.63 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 25 | 68 | 4.5 | 0.59 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 42 | 54 |

| 9. The instructor encouraged course participants to explore new concepts in this course. | 4.64 | 0.56 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 29 | 68 | 4.63 | 0.58 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 29 | 67 |

| 10. Instructor actions reinforced the development of a sense of community among course participants. | 4.32 | 0.82 | 0 | 4 | 11 | 36 | 50 | 4.29 | 0.81 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 29 | 50 |

| Direct Instruction | ||||||||||||||

| 11. The instructor helped to focus discussion on relevant issues in a way that helped me to learn. | 4.57 | 0.57 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 36 | 61 | 4.38 | 0.70 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 38 | 50 |

| 12. The instructor provided feedback that helped me understand my strengths and weaknesses relative to the course’s goals and objectives. | 4.18 | 0.82 | 0 | 4 | 14 | 43 | 32 | 4.42 | 0.78 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 25 | 58 |

| 13. The instructor provided feedback in a timely fashion. | 4.46 | 0.64 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 39 | 54 | 4.63 | 0.58 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 29 | 67 |

| SOCIAL PRESENCE | ||||||||||||||

| Affective Expression | ||||||||||||||

| 14. Getting to know other course participants gave me a sense of belonging in the course. | 4.39 | 0.89 | 0 | 4 | 14 | 21 | 61 | 4.58 | 1.00 | 4 | 4 | 29 | 42 | 21 |

| 15. I was able to form distinct impressions of some course participants. | 4.14 | 0.93 | 0 | 4 | 25 | 25 | 46 | 3.79 | 0.98 | 4 | 0 | 33 | 38 | 25 |

| 16. Online or web-based communication is an excellent medium for social interaction. | 4.07 | 1.01 | 0 | 11 | 14 | 32 | 43 | 3.39 | 1.27 | 9 | 17 | 22 | 30b | 22b |

| Open Communication | ||||||||||||||

| 17. I felt comfortable conversing through the online medium. | 3.96 | 0.95 | 4 | 0 | 21 | 46 | 29 | |||||||

| 18. I felt comfortable participating in the course discussions. | 4.25 | 0.65 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 54 | 36 | 4.12 | 1.09 | 4 | 4 | 13 | 29 | 50 |

| 19. I felt comfortable interacting with other course participants. | 4.39 | 0.63 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 46 | 46 | 4.33 | 0.70 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 42 | 46 |

| Group Cohesion | ||||||||||||||

| 20. I felt comfortable disagreeing with other course participants while still maintaining a sense of trust. | 4.18 | 0.77 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 39 | 39 | 4.21 | 0.59 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 63 | 29 |

| 21. I felt that my point of view was acknowledged by other course participants. | 4.36 | 0.68 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 43 | 46 | 4.29 | 0.69 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 46 | 42 |

| 22. Online discussions help me to develop a sense of collaboration. | 3.92 | 1.28 | 8 | 4 | 21 | 21 | 46 | |||||||

| COGNITIVE PRESENCE | ||||||||||||||

| Triggering Event | ||||||||||||||

| 23. Problems posed increased my interest in course issues. | 4.29 | 0.69 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 36 | 46 | 3.75 | 1.07 | 4 | 4 | 21 | 42 | 25 |

| 24. Course activities piqued my curiosity. | 4.18 | 0.86 | 0 | 7 | 7 | 46 | 39 | 4.12 | 0.96 | 0 | 8 | 13 | 33 | 46 |

| 25. I felt motivated to explore content related questions. | 4.25 | 0.93 | 0 | 7 | 11 | 32 | 50 | 4.00 | 0.59 | 0 | 4 | 13 | 58 | 25 |

| Exploration | ||||||||||||||

| 26. I utilized a variety of information sources to explore problems posed in this course. | 4.36 | 1.03 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 25 | 61 | 3.83 | 1.01 | 4 | 4 | 21 | 46 | 25 |

| 27. Brainstorming and finding relevant information helped me resolve content related questions. | 4.36 | 0.91 | 0 | 7 | 7 | 29 | 57 | 4.13 | 0.80 | 0 | 4 | 13 | 50 | 33 |

| 28. Online discussions were valuable in helping me appreciate different perspectives. | 4.04 | 1.00 | 4 | 0 | 21 | 38 | 38 | |||||||

| Integration | ||||||||||||||

| 29. Combining new information helped me answer questions raised in course activities. | 4.61 | 0.74 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 36 | 57 | 4.17 | 0.82 | 0 | 4 | 13 | 46 | 38 |

| 30. Learning activities helped me construct explanations/solutions. | 4.23 | 0.79 | 0 | 4 | 7 | 32 | 57 | 4.29 | 0.69 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 46 | 42 |

| 31. Reflection on course content and discussions helped me understand fundamental concepts in this class. | 4.21 | 0.96 | 0 | 7 | 14 | 29 | 50 | 4.17 | 1.00 | 4 | 0 | 17 | 33 | 46 |

| Resolution | ||||||||||||||

| 32. I can describe ways to test and apply the knowledge created in this course. | 4.54 | 0.64 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 32 | 61 | 4.13 | 0.74 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 46 | 33 |

| 33. I have developed solutions to course problems that can be applied in practice. | 4.36 | 0.87 | 0 | 7 | 4 | 36 | 54 | 3.96 | 0.86 | 0 | 4 | 25 | 42 | 29 |

| 34. I can apply the knowledge created in this course to my work or other non-class related activities. | 4.39 | 0.92 | 0 | 7 | 7 | 25 | 61 | 4.13 | 0.80 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 38 | 38 |

Note. Empty cells indicate response was not applicable. 1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = neutral; 4 = agree; 5 = strongly agree.

a N = 27; b N = 23.

From Community of Inquiry Survey, by B. Arbaugh, M. Cleveland-Innes, S. Diaz, D. R. Garrison, P. Ice, J. Richardson, P. Shea, and K. Swan, n.d., The Community of Inquiry (https://coi.athabascau.ca/coi-model/coi-survey/). CC BY-SA.

Elena Chudaeva is associate professor of physics and mathematics in the School of Liberal Arts and Sciences at George Brown College in Ontario, Canada. Current research interests include educational technology for active learning in STEM courses, online learning, and Universal Design for Learning. Email: echudaev@georgebrown.ca

Dr. Cynthia Blodgett is an international distance educator and course designer with over 30 years’ experience. For the past 20 years, she has taught graduate research and thesis development and supervised thesis and dissertation students at Athabasca University. Her research interests include disability studies, trauma-informed teaching, and student self-care. Email: cynthiab@athabascau.ca

Guilherme Loth, Master of Management Sciences, is the Senior Director of Remote Learning at Crandall University in Moncton, New Brunswick, Canada. His primary work and study are on innovation in online learning. Email: guilhermeloth@gmail.com

Thuvaragah Somaskantha, BMT-IEC Program Data Coordinator at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. She holds a BSc from the University of Waterloo, Canada, diploma in Health Information Management from George Brown College, Canada, and a CHIM designation in good standing with the Canadian Health Information Management Association. Email: thuvaragah.somaskantha@georgebrown.ca