Gregory MacKinnon, Acadia University, Canada

Tyler MacLean, Henan Experimental High School, China

The pandemic of 2020 frequently necessitated that offshore school teachers continue their instruction of Chinese children in the online format rather than face-to-face back in China; a so-called emergency remote teaching response. A required change in pedagogy accompanied a range of challenges in an effort to offer quality education to English as a Second Language (ESL) students. During the fall 2020-2021 academic year, a sample of 25 teachers and 3 principals provided feedback on those inherent challenges in a mixed method study consisting of surveys, interviews, and focus groups. Factors that impacted the delivery were identified in broad categories of teacher lifestyle, hindrances with technology, teaching practice, and pedagogical support. The findings were unique in that 1) they were nested in a response to a difficult context as opposed to a carefully planned online instruction and 2) second language students constituted a different learning cohort. This work further adds to the literature by suggesting that cognitive load, self-regulation, and attentional literacy deserve careful consideration when contexts of ESL learning with technology are implicated.

Keywords: ESL; online learning; offshore schools; COVID-19

La pandémie de 2020 a fréquemment nécessité que les enseignants des écoles délocalisées poursuivent leur instruction des enfants chinois en ligne plutôt qu’en présentiel en Chine ; une réponse dite d’enseignement à distance d’urgence. Un changement nécessaire de pédagogie s’est accompagné d’une série de défis dans le but d’offrir une éducation de qualité aux élèves en anglais langue seconde (ALS). Au cours de l’année scolaire d’automne 2020-2021, un échantillon de 25 enseignants et de 3 directeurs d’école ont fourni des commentaires sur ces défis inhérents dans le cadre d’une étude à méthode mixte composée d’enquêtes, d’entretiens et de groupes de discussion. Les facteurs qui ont eu un impact sur la prestation ont été identifiés dans les grandes catégories de : style de vie des enseignants, les obstacles liés à la technologie, les pratiques de enseignement et le soutien pédagogique. Les résultats étaient uniques en ce que 1) ils étaient liés à une réponse à un contexte difficile par opposition à un enseignement en ligne soigneusement planifié et 2) les élèves en langue seconde constituent une cohorte d’apprentissage différente. Ce travail contribue à la littérature en suggérant que la charge cognitive, l’autorégulation et la littératie attentionnelle méritent une attention particulière lorsque des contextes d’apprentissage de l’anglais langue seconde avec la technologie sont impliqués.

Mots-clés : ALS ; apprentissage en ligne ; écoles délocalisées ; COVID-19

Since its onset in March 2020, the coronavirus has had considerable influence on public education around the world. Many of the first order impacts included closure of schools and reduction of curriculum covered, but most prominently, the movement to online instruction. This has led to a phenomenon referred to in the literature (Hodges et al., 2020) as Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT).

North American teachers are often employed teaching North American curriculum in Chinese schools. The rapid spread of COVID-19 created a unique situation when so-called offshore school teachers returned to their home countries in the vicinity of the Chinese Spring Festival. Coupled with the implementation of stringent travel restrictions, their respective Chinese school administrators insisted that teachers be prepared to teach core subjects in English to Chinese children in their schools. Essentially teachers were asked in an emergency mode to entrust technology to continue teaching via an online environment. This study, conducted during the academic year beginning September 2021, sought to investigate the factors of consideration as teachers transitioned to teaching core subjects to second-language students in English over the Internet. While the transition from face-to-face teaching to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic has been well characterized in the literature, there is a paucity of research describing the unique setting of ESL learning.

This paper adds to the literature by suggesting ways that teachers can best navigate and mitigate the effects of a rapid transition from classroom teaching of second language students to online learning with limited tools or inherent pedagogies.

There are many perceived positive impacts of online learning. Flexibility and convenience are routinely mentioned in the literature. Xia et al., (2013) allude to the ability to study anywhere at any time while Famularsih (2020) notes that students can support their learning using social media connections regardless of time zone differences.

Further benefits noted in the literature include being able to give personal support and advice through online messaging as well as the ability to repeatedly refer to support materials including videos, diagrams, pictures, and graphic organizers (Gao & Zhang, 2020). It has been argued that students have extended time for thinking and response, a benefit that fosters more independent learning thus instilling more confidence and efficacy as a learner (Krishnan et al., 2020).

Bailey and Lee (2020) suggest that there are a variety of benefits for teachers who teach online. For instance, they posit that the skills teachers learn from teaching online have the potential to improve their overall pedagogy, instructional methods, and curriculum design for face-to-face teaching.

Voogt and Knezek (2021) aptly framed challenges of online learning using a micro/meso/ macro framework. At the micro level, cited literature supports challenges that include: (a) teaching from home, (b) attitudes towards online learning, and (c) readiness to teach online. At the mesa level worldwide literature supports (a) lack of in-person curriculum alignment with online learning, (b) difficulties with formative assessment, and (c) poor Internet connections. Further, at the macro level their meta-analysis included support for challenges including: (a) availability of resources, (b) cyber security, and (c) quality of online teaching.

These challenges and corresponding solutions have been the subject of recent research (Coomey & Stephenson, 2018; Gillet-Swan, 2017; Kebritchi et al., 2017).

While there are many issues associated with language teaching and learning, it is worth mentioning a few here. Internet connection problems are the most noted drawback of online language learning across continents (Atmojo & Nugroho, 2020; Krishnan et al., 2020; Levy, 2009; Sari, 2021). While Famularsih (2020) reported that slow speed Internet is common across Indonesia with over 70% of participants causing access issues. Fu and Zhou (2020) claim that hardware facilities and Wi-Fi conditions are uneven across schools in China. Atmojo and Nugroho (2020) have suggested that unevenly distributed income across a nation creates barriers for effective online language learning. The relationship between the digital divide and language learning has been well established (Lozano & Izquierdo, 2019).

Teachers’ preparedness for online teaching is a concern especially with regard to English language learning. Several studies suggest that teachers are not trained in the necessary technical and effective online support platforms (Fu & Zhou, 2020; MacIntyre et al., 2020). Atmojo and Nugroho (2020) have argued that teachers are lacking in professional development as they are not engaging students with the latest technologies such as artificial intelligence, gaming, augmented reality, and virtual reality.

It is important to note that teachers in this pandemic context, did not have the opportunity to systematically design their online learning; instead they were responding to an emergency situation, the process of which would inherently and predictably affect the quality of the instruction (Hodges et al., 2020). Some kinds of activities that are designed for in person classes can be less effective in the online learning setting. In language learning, conversations tend to suffer while writing activities seem to thrive due to its asynchronous nature (Bailey & Lee, 2020). Gao and Zhang (2020) note that timely student and teacher interactions are very difficult. Famularsih (2020) recommends that not all material is ideal for online learning and there is often a lack of meaningful interaction between student and instructor. Pazilah et al. (2019) compiled a variety of potential impediments to productive online language learning, including student’s difficulty in understanding instruction, difficulty giving feedback in real time, language proficiency, and eagerness to participate.

Managing the online classroom can prove problematic. Gao and Zhang (2020) suggest a variety of reasons for this including: lack of non-verbal cues, punctuality of students both for class and submitting assignments, not being able to see all the students and finally, the perception that some students equate online learning to a holiday (Atmojo & Nugroho, 2020).

Given the inherent nature of online learning, Fu and Zhou (2020) suggest individualized learning is difficult. This is corroborated by Atmojo and Nugroho (2020) who cite the difficulty in teaching students with low cognition and various learning styles. They further allude to the additional time it takes for a teacher to attend properly and completely to those with learning challenges.

The prospect of moving from a traditional classroom to one of online learning has been daunting for many teachers. Two of the most intimidating factors noted in the literature are a teacher’s lack of technological competence and further, a dearth of personal strategies for online pedagogy (Dashtestani, 2014). While teachers desperately wanted and needed training in these areas, the quick transition time was difficult to overcome logistically for most education systems (Atmojo & Nugroho, 2020; Bailey & Lee, 2020).

Provincial governments and private educational institutes in Canada have created partnerships with schools in China such that Chinese children can study provincially-endorsed curriculum, and upon successful examination receive graduating diplomas. This has obvious advantages for families who want their children to seamlessly apply to North American universities. One such example is the Nova Scotia government that operates and supports approximately 15 schools in China1. These schools typically offer Grades 10-12 Nova Scotia curriculum to class sizes of 15-30 Chinese teenagers. The Nova Scotia schools are normally housed within larger Chinese educational institutions but are segregated from the general student body. The operation of the school is closely monitored by local school officials in terms of the space but operationally, the Nova Scotia government employs its own monitoring system, policies, and matriculation protocols. With two collaborating administrations, this poses unique challenges (MacKinnon & MacLean, 2021).

Core subjects are taught in English and principals (often retired educators from North America) are charged with some responsibility for filtering student applicants based on English fluency (MacKinnon & MacLean, 2021). In this study, which included 26 teachers from a variety of North American offshore schools, 54% taught grade 10 which arguably would be the level facing the biggest challenge around English comprehension and fluency. Teachers in the sample saw student demographics distributed, specifically: 38% (3-5 years), 31 % (6-10 years), and 31% (over 10 years). Of the sample, 69% reported that the pandemic-induced online teaching task was their first exposure to this pedagogy. This sample of teachers taught from home countries: 46% Canada, 31% USA, 15% African nations, and the remainder distributed across other nations. Teachers were largely charged with using technologies at their disposal with little direction or support from their institutions.

At the beginning of the pandemic, most cities in China were forced into strict lockdowns (Ilmmer et al., 2021) which necessitated students working from their private homes to learn on a personal device. In this case, each student would log into a class meeting at assigned times to learn. As the incidence of the COVID-19 virus receded, students were expected to return to the schools. This often created a situation where all students were in a classroom and the online teacher was streamed from their home country and viewed on a large screen.

Most teachers were expected to deliver their typical schedule; this required remaining in front of their computer screen for their daily schedule. Because teachers were now living abroad, this could have them in a time zone twelve hours removed from Chinese time, that is, a typical day would entail teaching from 9 pm to 3 am.

The researchers have a distinctive lens from which to interpret this teaching and learning environment; a North American teacher with nearly 10 years’ experience teaching in Chinese offshore schools and a university professor with 20 years’ experience working with teacher interns placed in Chinese schools. Both have extensive experience and certified preparation to teach ESL. The study clearly has limitations and delimitations in that it takes place in a convenience sample of schools with associated teachers and principals. The regional context necessarily invokes certain educational values and political constraints. The study is unique in that it refers to both second language learners and ESL teachers from across the world. Arguably, this highlights a particular group of factors that go beyond standard online learning challenges (Voogt & Knezek, 2021).

The goal of the research was to examine an emergency-induced phenomenon of transitioning from face-to-face teaching in a unique ESL context to online learning. As such, the study was intended to identify important factors to consider whilst moving forward quickly to an online format with little time to investigate effective online learning tenets. Within an action research methodology aimed at improving future instruction (Beaulieu, 2013; Stringer & Aragon, 2021), the approach accessed both qualitative and quantitative indicators to establish said factors for improving teaching and learning in these unique circumstances.

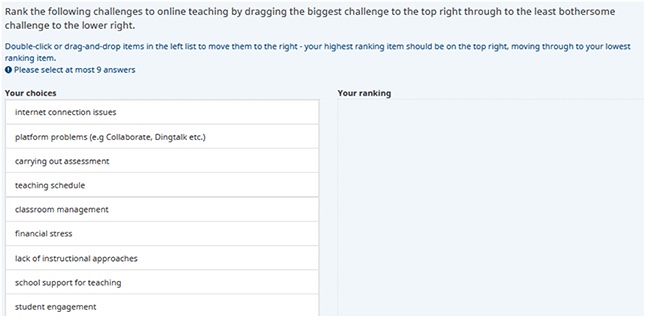

The investigation explored the lived experience of 26 teachers and 3 principals who adapted to online teaching of ESL learners. A question-focusing session was undertaken by the researchers with due consideration of the literature in order to create a general survey defining the scope of the system to be studied. The survey culminated in questions in large categories of lifestyle, technology, teaching practices, and support. The survey also retrieved demographic information including teacher location, grade level taught, professional experience, and extent of experience with online teaching. Furthermore, the survey included a series of context statements about their experience that participants were asked to rate agreement on a five-point Likert scale with a range from strongly agree to strongly disagree (Appendix 1). Finally, the survey posed ranking questions to highlight the relative importance of predictable challenges with this teaching scenario (Appendix 2). The survey was field tested (with three readers unconnected to the research) to remove ambiguity in statements. The survey was administered electronically to 26 teacher participants. The problem of a careless responder was addressed by the inclusion of reverse-keyed questions (Kam & Meyer, 2015). If three of the reverse keyed questions were inconsistent the survey was removed from the sample. One such survey result was removed from the empirical data set.

Means were calculated for each of the Likert responses in the survey serving only to identify trends as opposed to implying a statistical study. After analyzing the survey trends, the researchers developed a standardized open ended interview schedule (Patton, 2002). Participants for the interview were purposefully chosen for diversity in the location from which they were teaching and to ensure a variance of schools and programs to mitigate a biased response. Seven participants were chosen to be interviewed using Zoom® software. Interview questions were posed over a typical duration of 45–70 minutes, audio recorded then transcribed into a textual account. Transcripts of the interviews were independently coded by the two researchers in an iterative process (Huberman & Miles, 2002). Axial coding was applied wherein categories were constantly enlarged and collapsed; a reorganization to adequately cover a range of subcategories (Gasson, 2004).

In order to understand the expectations of principals and their leadership contexts as they tasked teachers with online teaching, we also chose to interview (by Zoom®) a convenience sample of three principals in Chinese offshore schools. These interviews were transcribed and analyzed using a constant comparative coding approach as we attempted to ground all empirical materials in previously gathered evidence.

The culmination of survey and interviews led to a series of conclusions regarding the phenomena. These cumulative findings were subjected to peer debriefing (Guba, 1981) accessing a research colleague unassociated with the current study. In an effort to corroborate and extend these empirical findings, a focus group (Kreuger & Casey, 2014) was conducted as a form of member check (Guba, 1981). Five participants were invited from the initial sample (n=26) for the focus group. Text accounts from interviews with principals were also used as evidential artefacts to corroborate the findings.

There were a variety of challenges that presented themselves. In the survey, participants were asked to rank a list of challenges from least to most challenging. The highest rated challenges were poor Internet connection, teaching schedule, platform issues, and lack of support from the schools that they worked in. The lowest rated challenges were financial issues and classroom management. The interviews and focus group sessions served to illuminate the rationale behind survey trends; the aggregated data served to identify themes which will be addressed below.

Note that participants who have been quoted within this report are hereafter designated (after the quote) with I for interviewee, F for focus group participant and P for principal. The number following the letter indicates an anonymous identifier for each individual respondent to label different speakers.

Especially at the onset of the shift to online learning, a work/life balance was difficult to achieve for many, with 58% of the sample claiming in surveys that they had struggled in this area. They suggested in subsequent interviews that having to learn how to teach in an online format was akin to relearning your entire profession with little to no training in how to do so. This added considerable pressure to become adequate as a teacher using online teaching strategies, navigating the technology, and negotiating platforms themselves. This was especially challenging for those who were not current with instructional technology, much less favourable in their predispositions to technology in teaching. This phenomenon of reduced efficacy has been aptly identified in the literature by Bailey and Lee (2020). Focus group sessions confirmed that this dedication of additional professional time infringed on their lifestyle considerably. As stated by one interviewee, “The unfamiliarity was a cause of a lot of undue stress. Everything was different now and that can be terrifying” (I2).

Teachers who were conducting their classes from outside of Asia had to contend with up to 12 hours of time difference by comparison to a typical teaching day onsite. This meant that teachers began their teaching day in the late evening and continued through the night until the early morning hours. Readjusting to such a schedule proved challenging. Interviewees in this situation were unanimous in stating that teaching quality, as well as their personal quality of life was negatively impacted. In an interview it was shared, “In a normal school atmosphere, you have your evenings and weekends but now it seemed endless. You need to be available 24/7” (F2).

In general, the benefits of electronic communication are abundantly apparent in the online context, however, granting the students constant access to the teachers via text messaging apps (e.g., Ding Talk, WeChat) was an adjustment for most interviewees. Students would often message at all hours of the night and day seeking assistance. Teachers tried their best to return messages as soon as possible. Interviews made it clear that this 24/7 access had the potential to be overwhelming unless firm time boundaries were set.

You are asking teachers to do the impossible. To readjust their whole schedule and maintain some sense or normality in their daily lives while you are continuously communicating to students on Ding Talk. There is no end and there is no privacy. (I3)

Over 80% of survey participants found it difficult to maintain a healthy lifestyle. Interviewees cited the schedule change with the lack of sleep and loss of structure in their daily lives as the key challenges. It was also noted that the sedentary lifestyle that accompanied teaching from a laptop was in stark contrast to the more active classroom teaching they normally undertook.

Half of the survey sample communicated undue stress as a direct result of the health issues associated with the current pandemic. Coupled with the teaching uncertainty, these factors were identified as the biggest stressors. Some participants were forced to find a new place to live or even reconsider what country they could afford to live in. Not knowing whether a return to China was imminent also contributed to teacher stress. This consideration was intensified given the dangers of travel during a pandemic. Often information relayed to teachers from their employers was delayed or unclear. One interviewee suggested this had something to do with the Chinese culture of communication in which one does not want to disappoint or lose face. This propensity for nebulous communication has been observed in similar Chinese school systems (MacKinnon & Shields, 2020; MacKinnon & MacLean, 2021).

MacIntyre et al. (2020) found that teachers had various ways to cope with the extra stress brought about by this uncertain situation. The most frequently used methods consisted of accepting the situation and dealing with it through activity or reframing and seeking emotional support. Advanced planning was also a frequently used coping strategy, yet this was much more difficult due to the uncertainty that accompanied the unique situation of a pandemic. The fact that most teachers were given less than a week to transition from face-to-face to online learning made coping a particularly difficult response.

Financial problems were also reported by half of the participants in the survey. While working in offshore schools in China, a suitable place to stay is often provided by the employer. No longer able to reside permanently in China, many of the interviewees had to find accommodation in their home country. While some had family that could house them, many had to rent a home which was an expense not previously accounted for in their budgeting. The cost of living in China is relatively inexpensive compared to many of the participants’ home countries. This added significant financial pressure on teachers. For some, it was difficult to access money that was earned and deposited in a Chinese bank. According to the laws of the People’s Republic of China, there are limits to how much money can be withdrawn abroad per year. Sometimes employers were not helpful in finding solutions to this problem. As stated in an interview with one principal,

There was stress because of the pay issue, some teachers were struggling financially and unable to access their pay. They wanted to be paid in their country. They were told this was possible, but it took several pays before it was done. (P1)

Half of the survey respondents reported problems with both Internet connection and the platform that was used to conduct classes. When students were online at home, if one student was having a problem with the teaching platform, it became a problem for the entire class as the teacher was often focused on troubleshooting and communicating with that student. When students moved back to the school, it remained an issue because the larger school had their own Internet needs that competed for bandwidth. A principal recounted, “The Internet connection at the school is a real problem” (P1). This was corroborated in a teacher interview, “the biggest problem right now is, I think, Internet speed, the students sometimes complain that they have trouble connecting because of Internet speed” (I5).

There was often significant Internet lag. When conducting conversations in class, this led to teachers repeatedly asking students to repeat themselves. This often caused embarrassment for students and led to an unwillingness to participate in class discussions. Problems with audio were noted as being more difficult when the students were moved to the classroom while the teacher was on the main screen. Microphones were often unavailable or of poor quality, making it harder to hear what the students had to say. As relayed by two participants in the focus group, “There was not one microphone in the class even though I asked repeatedly” (F1) and “I could rarely hear the students because of poor audio. They never got to speak in my class, and I have no idea if they understood my directions or not” (F5).

Many applications that would be ideal for teaching in North America were not supported in China and blocked by a firewall. This included Google Classroom®, Pear Deck® and DropBox®. Although Zoom® was used by some for a means of teaching, one interviewee claimed it was much slower than familiar domestic use. Characteristic feedback follows,

From what I am only now learning about it, it would have been a dream to use Google Classroom but that is just not possible in China. I used Padlet, but sometimes students have problems logging in and accessing it. (F3)

From teacher interviews, it seemed that teachers were grasping at whatever was available with very little support. One interviewee said, “I didn’t have one centralized platform like Google Classroom to rely on and that is what a lot of online teachers have, and this is one thing that has really bothered me” (I7). The lack of availability of these applications often forced teachers to use Chinese versions of familiar technology such as the communication applications Ding Talk® or WeChat®. One persistent complaint from participants was that these platforms did not provide a drop box for assignments. This caused confusion when collecting student assignments. Participants reported problems with files not being uniform in format or corrupted or in certain applications expired in their accessibility. One teacher in the sample was accepting assignments by email and his storage space was completely exhausted. Almost two-thirds of teachers found collecting and marking assignments problematic. They also cited assessment issues such as: greater time spent marking, difficulty finding the assessments to grade, and more time was required to follow-up with students. Those with a detailed plan such as moving assignments to folders right away or those who were set up with a platform such as Moodle® or Schoology® (with the assistance of their North American governing body), fared much better in this organizational task.

Regardless of the challenges, over time teachers found ways to improve the experience from a technological standpoint. Those who were using Zoom® found that using breakout rooms was highly effective to get more personal connection with a small group of students. This however was not often feasible when students had returned to the classroom as they were often without laptops or unable to respond due to issues of audio-feedback when the class was using a projected screen of the teacher.

Those teachers who recorded their lectures using technology offered students another learning tool. With the inherent language barrier, it was a definite advantage to provide a video that students could watch repeatedly (asynchronously). Said one teacher, “I recorded videos and they watched them on their own time. While we were in the designated class hours I could help them more with their questions” (F5).

Teachers also found text-message, while time consuming, was an effective technology for scaffolding instruction and establishing improved relationships. Students were comfortable with this technology so, as alluded to previously, boundaries had to be set regarding communication with the teacher; especially given 12-hour time zone differences. In the focus group, one respondent suggested, “Actually I found I could sometimes make the feedback more personal in this manner, as you are having a text message conversation with them about it a lot of the time” (F1).

Based on the feedback from our cohort of teachers and principals, technologies that seemed to be most often relied upon in Asian contexts include: https://kahoot.com/, https://quizlet.com/, https://padlet.com/, https://new.edmodo.com/, https://nearpod.com, and https://www.classmarker.com/.

Across all the empirical feedback, teachers expressed disappointment that they were not serving their students well because COVID-19 had forced a very rapid pedagogical transition. The face-to-face setting traditionally offered not only important conversational language development, but personal connection with students and other faculty that enhanced and supported the learning environment. Teachers were unanimous in admitting that the technology, while possessing intrinsic potential, was not able to bridge the pedagogical gap brought on by their inexperience and the systemic hurdles. In an interview one teacher shared, “I think generally teachers want to do a good job and get frustrated when there are obstacles preventing them from giving good quality instruction” (I3). The frustration was evident in comments such as, “There was no training. It was like ‘alright go ahead we expect you to do your best and be successful even though you have no idea what you are doing’!” (I1). The lack of social construction of knowledge was captured in this expression,

I think there was a lot of informal learning in class when you were on site, you know a lot of learning happened. Those conversations in the hallway and the basketball pitch aren’t happening now and it really hurts, a big loss. (I2)

Teaching practices were forced to change because of the new mode of delivery. According to teachers in this sample, conducting classroom conversation was no longer an effective way of teaching due to the technological and logistical challenges, a finding already aptly noted in the literature (Famularsih, 2020; Gao & Zhang, 2020). Valid testing of students was difficult as it was not feasible to monitor students’ computers. Teachers suggested teaching assistants be present during testing but this wasn’t always possible. Some interviewees suggested that cheating on tests was definitely occurring. According to one interviewee, “They were cheating more, copying more and the lower achieving students... I didn’t hear from them at all. We completely lost them” (F1).

The exchange of assessment materials was problematic and, in a context where typically Chinese parents can be pre-occupied with grades, this was exacerbated. As recounted by one interviewee,

It was hard for me to keep track of assignments. I got my co-teacher to take pictures and I was receiving 200 plus documents on my phone. I didn’t open them in time and some expired, so I had to ask them to send some again. It was not efficient in terms of organization. (I7)

Differentiation of instruction, in order to respond to the continuum of learning abilities and styles, was deemed more difficult by the majority of the survey respondents. Participants mentioned that not being present to see student’s progress firsthand posed a problem. Students could have easily collaborated on some assessments that were meant to be done individually. Previously, teachers in this cohort would have taught these students in person when they had started in the Grade 10 level of the school. Because of the shift to online learning, that particular mode of interaction was compromised. This is not to say the teachers did not make an effort to determine student backgrounds; it was just a new way for them to connect with students and they were admittedly lacking appropriate effective approaches in the online environment. Without a knowledge of students’ personal interests and preferred learning styles, it was difficult to meet the needs of individual students. Whether the students already knew the teacher or not, participants were unanimous in saying that a level of personal connection was missing when classes moved online. The frustration due to the lack of communication is evident in these two focus group excerpts, “Some students I didn’t even hear from or receive anything from the entire duration” (F3). “It hurts me to say it, but it was a write off. I wasn’t able to challenge the more academic students and I wasn’t able to help the less academic students” (F2).

Participant teachers claimed that, although all aspects of learning were compromised, it was specifically the students’ skills in the English language that suffered most. The switch to online learning in most cases got rid of any informal opportunity to speak while technological and audio problems made speaking in the class difficult as well. By all accounts, any teacher assistant that was physically in the classroom spoke in the Chinese language and rarely encouraged an English-speaking environment. Although all grade levels were impacted negatively from the change, Grade 10 students just entering the program seemed to be hit the hardest. The participants suspected this was mostly due to it being their first time in a fully English language program but not being exposed to an immersive environment. As predicted by one principal,

Now the Grade 10s, on the other hand, are struggling this year and it’s certainly, it’s because they are new to the program, their English skills are going to be, you know, less developed and it’s going to be – it’s going to be – an issue for them. (P1)

Some teachers found ways to do their best to recreate the personal connection that was diminished in the online classroom. One participant hosted daily morning meetings where students could communicate with the teacher and fellow students freely about random topics of interest and concern. This 20-minute session allowed for enhanced personal connections and gave extra opportunity for the students to practice their English-speaking skills. As proffered by one teacher, “We had a morning meeting with the students. It wasn’t always just class meetings. Sometimes we logged in just to chat. This helped a lot and led to better relationships” (F4).

With the challenges that traditional assessment presented, many teachers (with support from administration), found that authentic assessment worked well in the online format. Teachers suggested they capitalized in part on the established benefits of project-based learning (Aldabbus, 2018; Astuti et al., 2021). In the focus group one participant suggested, “Project-based learning is a more authentic learning experience for the students. It could be planned with outcomes in mind and in accordance to student ability.” (F1).

The Chinese schools remained supportive as the learning shifted to the online domain. In the period February-April 2020 students were learning online yet were in the home environment. When students transitioned from home back to the classroom for online learning (May-June 2020), often Chinese support teachers were present for technological troubleshooting, supervising, and assisting students as needed. In most cases, curriculum support classes led by Chinese teachers continued with little disruption. While this was a reactive solution to an enormous transition, teachers were unanimous in suggesting that students were not receiving effective English learning even as they learned the core subjects. For instance, one teacher in the focus group said, “An English teacher is not in the room. This makes it hard to ensure English is being spoken” (F2).

Despite this level of support, the majority of teachers felt that the Chinese schools could have done a much better job supporting the distant teachers in a variety of areas. Sometimes much-needed resources were not purchased a simple example was the resistance to improving the audio-visual equipment in classrooms; many teachers alluded to poor audio for both students and teacher which was clearly detrimental to language learning. Although one school mandated 45-minute classes and used Zoom® as their choice technology for teaching, the school then reduced class time to 40 minutes to avoid paying for the premium version of Zoom®. The reduction of class duration for an already precarious teaching mode impacted learning. Nonetheless, teachers were sensitive to the decision-making that accompanied the pedagogical shift. “In all honesty I can’t really fault them because just as I was unprepared, they were also unprepared” (I1).

The focus group suggested that, at times, the administration of the Chinese school was demanding better performance from the teachers with few suggestions to assist them. Teachers communicated discontent with this attitude given they were under so much pressure to perform their duties in an ever-changing pedagogical landscape with an overwhelming workload. For some, there was pressure from Chinese schools to return to China to be present for live classes; this was despite the fact it may be unsafe, not economically feasible, or perhaps not even lawfully possible to return. This was deemed incredibly unsupportive by those who were affected. It was uncovered in interviews of teachers and principals that Chinese parents/administration often had the opinion that teachers did not want to return to China. One principal recounted being accused of telling his staff not to return. Conversely, foreign teachers found it odd that the Chinese administration were not doing enough to help them get back to their teaching posts in China (i.e., assisting with travel documents, work visas, vaccines, etc.).

The North American governing bodies were far more supportive of the teachers’ safety and interests in this situation, but according to some teachers, fell short in other areas of concern. Teachers in the focus group made these comments of their principals (as representatives of the North American body), “My principal just gave students and parents what they wanted. They also put a lot of pressure on us to get back to China. This was uncalled for and added a lot of extra stress” (F3). “We taught from 9 PM at night to 3 AM in the morning. I think she could have fought for us a little more to change this" (F5).

It was evident from interviews, that some principals set up platforms for sharing resources or even the establishment of online professional learning communities. In some cases, they created a Moodle® for a program where assignments could be more easily shared and submitted. In interviews, the principals had a more positive attitude towards the helpfulness of the North American governing bodies than the teachers. They cited several supports which included: a compilation of online learning resources, a summer learning academy with online learning workshops, and a question-feedback resource for principals. The range, quality, and usefulness of the resources were questioned by teachers in interviews and the focus group. For example, one respondent said, “We needed more help with adaptation of resources that can work in China. Perhaps the North American Organization should have tested programs first before recommending we use them in China. Some of them didn’t work” (F2). Teachers felt they needed far more training as stated by one teacher in the focus group, “We should have had a lot of training sessions on how to use the technology. Especially for the more traditional teachers. Some older folks I know were completely drowned and it wasn’t fair” (F1).

In order to corroborate teacher observations and better understand the challenges of a unique pedagogical situation, it was deemed useful to get a system perspective from educational administrators in the offshore schools. Three principals were interviewed separately using Zoom®. These 60-minute interviews were audio recorded, transcribed, and coded for emergent trends (Huberman & Miles, 2002).

The following are common challenges these experienced educators noted.

When students began online learning from home, principals reported that teachers made effective use of breakout rooms and allowed children to use their phones to support learning (i.e., teacher questions, interaction with other students). Teachers often asked students to leave their video on so that they might see their interaction and observe facial expression in terms of English pronunciation; this had varying success.

Principals all agreed that the transition of children from home computers (at the onset of COVID-19) back to the classroom (with the teacher still communicating from abroad) was problematic. The biggest hurdle was poor communication. The microphone systems in classrooms as well as the projected teacher audio were poor. Students were not always visible online to the teacher. There were Chinese chaperones in some of the classrooms, but they were entrusted more with management than translation and the children were well-aware these adults had no power to enforce classroom conduct. Given that teachers needed to give instructions and students needed to respond to discussion prompts, not being able to hear was a big problem. From a teacher’s perspective, not being able to coach children or hear their pronunciation seriously compromised the English language learning not just the subject learning. Further, in an effort to maintain lower costs, by subscribing to shorter duration communication tools (Zoom for 40 minutes), class times were reduced. Coupled with intermittent Internet dropouts, the classroom approach was not considered seamless.

Principals frequently heard that teachers were fatigued because of the time-zone difference. Many teachers were teaching from 9 pm to 3 am their local time and spent that time entirely in front of a screen. Into the evening, Chinese-time, they were receiving texts and social media questions from their students. Teachers often expressed financial pressures as they needed accommodation with living expenses in their home countries. First and foremost, with the rapid onset of online learning, teachers were in need of professional development support from their principals especially those that had little aptitude for instructional technology. This is not a surprising finding as the literature documents the instructional leadership responsibility as paramount during the pandemic (Westberry et al., 2021). Further, Westberry et al. (2021) suggested themes of concern for virtual principals during the pandemic, such as, “increased presence and communication, projecting calm during uncertainty, displaying flexibility, empathy and patience, knowledge of technological capability and a systems approach to sustained instructional leadership” (p1). From a cultural perspective, teachers and principals shared the concern that Chinese parents expected teachers to return to their teaching post in China. As parents, they had sensed a lack of language learning in the online environment. This of course was beyond the control of teachers due to international travel constraints, yet parents often thought it was a laziness or lack of professionalism on the part of the teacher. This public attitude invoked another pressure that teachers frequently felt.

While the impact of the pandemic on public school learning has been well documented in the literature, an account of the emergency remote teaching that has occurred in ESL classrooms is rare.

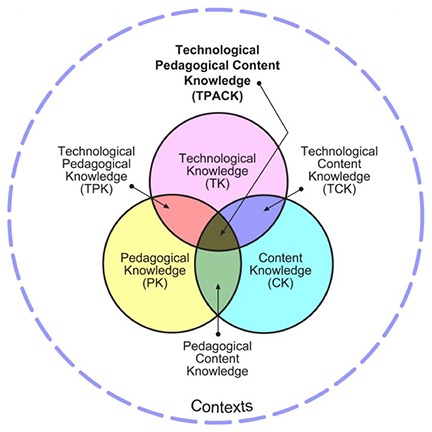

The Technological, Pedagogical, Content Knowledge (TPACK) model (Figure 1) reminds us that while teachers may possess content and pedagogical knowledge, their confidence and ability to empower both domains with technology cannot be presumed. This model (Mishra & Koehler, 2006) aptly prompts us to think about how our content knowledge is best taught and further how technology can empower that teaching through unique pedagogies. In the pandemic context, the teachers were tasked, rather suddenly, with leveraging technology to teach core subjects. This was not a trivial undertaking as many teachers would have already adopted signature classroom pedagogies (Gurung et al., 2009; Ham & Schueller, 2012) and best ways of teaching their subject unrelated to technological interventions.

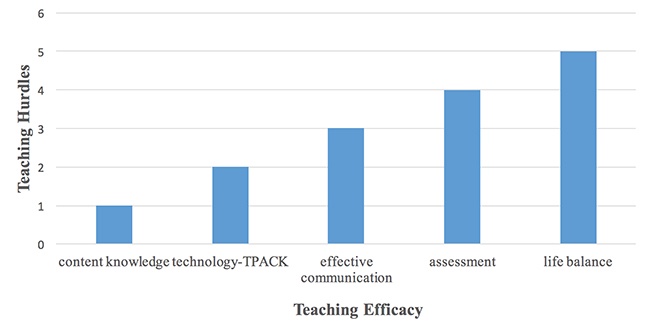

The aforementioned research identifies some of the challenges faced by teachers as they negotiated the rapid change to online learning. Our sample was a dedicated group of professionals who sincerely wanted to offer quality education in a difficult circumstance. Figure 2 depicts a summary of the hurdles to effective instruction in this context.

Figure 1

A Model For Considering How Technology and Pedagogy Intersect: TPACK

Note. Used with permission from source: http://tpack.org

Figure 2

What Did Teachers Need to Overcome?

From the students’ perspective, one must consider the predictable challenge of not only using technology, not only learning the core subject, but doing so in a different language other than their native tongue. While the literature has documented (Voogt & Knezek, 2021) significant challenges with a single-layer learning hurdle (i.e., learning in the online format), one might predict a significant cognitive load (Sweller, 2019) placed on a student trying to learn in this setting in an unfamiliar language. Based on the work of Atkinson and Shiffrin (1968), Sweller’s cognitive load theory is built upon the premise that incoming information is first dealt with in sensory memory, then working memory, and finally long-term memory. It further suggests that working memory is limited in its capacity and that learning can be affected detrimentally if multiple activities are happening in the learning space. Sweller has deconstructed the working memory process to consider concepts of split attention and dual modalities as they relate to mixing auditory and visual information. Suffice to say, multiple streams of knowledge via different modalities reduces working memory and therefore by association, long-term memory (i.e., retention and learning).

In many cases this may be complicated with the implied nature and culture of learning at home. When language and culture are real barriers, it requires a tremendous discipline to avoid distraction on the student’s behalf. Pegrum and Palalas (2021) draw our attention to the notion of attentional literacy. In their discussion, they suggest, “When students learn online, they do so within a wider context of digital disarray, marked by distraction, disorder and disconnection, which research shows to be far from conducive to effective learning” (p 1). This is firmly entrenched in literature (Bandura, 1991; Ackerman, 2021) concerning students’ ability to self-regulate a disciplined approached in the absence of a structured and monitored classroom. When Chinese children were working from home with their distant teachers, the extent of learning was clearly dependent on their ability to attend classes in front of a computer. In order to avoid distractions and maintain concentration, students would have to regulate their behaviour in disciplined ways. Teachers in interviews were not convinced that students were parent-monitored much less present (physically and cognitively) during their classes. Figure 3 offers a simplistic summary of what our research suggests students were likely to have experienced in trying to learn in these contexts.

Figure 3

What Did Students Need to Overcome?

In preparing for a similar context, the culmination of the empirical feedback from teachers and principals highlights certain areas of suggested improvement in this system of teaching core subjects online in English to non-native speakers:

While the researchers believe these findings and recommendations are representative of similar settings, the study is clearly limited by the convenience sample. The categories of challenges go beyond a typical well-planned online course and highlight instead the intuitive response of teachers put in an emergency situation where reactive pedagogical decisions were made.

Ackerman, C. (2021, November 25). What is self-regulation? (+95 skills and strategies). PositivePsychology.com. https://positivepsychology.com/self-regulation/

Aldabbus, S. (2018). Project-based learning: Implementation & challenges. International Journal of Education, Learning and Development, 6(3), 71-79.

Astuti, D., Syukri, S., Nurfaidah, S., & Atikah, D. (2021). EFL students’ perceptions of the benefits of Project-based learning in translation class. International Journal of Transdisciplinary Knowledge, 15-30. https://doi.org/10.31332/ijtk.v2i1.3

Atkinson, R. C., & Shiffrin, R. M. (1968). Human memory: A proposed system and its control processes. In Psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 2, pp. 89-195). Academic Press.

Atmojo, A. E., & Nugroho, A. (2020). EFL classes must go online! teaching activities and challenges during COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Register Journal, 13(1), 49-76. https://doi.org/10.18326/rgt.v13i1.49-76

Bailey, D. R. & Lee, K. R. (2020). Learning from experience in the midst of Covid-19: Benefits, challenges, and strategies in online teaching. Computer-Assisted Language Learning Electronic Journal, 21(2), 178-198.

Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 248-287.

Beaulieu, R. (2013). Action research: Trends and variations. Canadian Journal of Action Research, 14(3), 29-39. https://doi.org/10.33524/cjar.v14i3.99

Coomey, M., & Stephenson, J. (2018). Online learning: It is all about dialogue, involvement, support and control—according to the research. In Teaching & learning online (pp. 37-52). Routledge.

Dashtestani, R. (2014). English as a foreign language: Teachers’ perspectives on implementing online instruction in the Iranian EFL context. Research in Learning Technology, 22. https://doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v22.20142

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In Handbook of Qualitative Research; edited by Norman K. Denzin; Yvona S. Lincoln. Sage.

Famularsih, S. (2020). Students’ experiences in using online learning applications due to COVID-19 in English classroom. Studies in Learning and Teaching, 1(2), 112-121. https://doi.org/10.46627/silet.v1i2.40

Fu, W., and Zhou, H. (2020). Challenges brought by 2019-nCoV epidemic to online education in China and coping strategies. J. Hebei Normal Univ. (Educ. Sci.), 22, 14-18.

Gao, L. X., & Zhang, L. J. (2020). Teacher learning in difficult times: Examining foreign language teachers’ cognitions about online teaching to tide over covid-19. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.549653

Gasson, S. (2004). Rigor in grounded theory research: An interpretive perspective on generating theory from qualitative field studies. In The handbook of information systems research (pp. 79-102). IGI Global.

Gillett-Swan, J. (2017). The challenges of online learning: Supporting and engaging the isolated learner. Journal of Learning Design, 10(1), 20-30. https://doi.org/10.5204/jld.v9i3.293

Guba, E. (1981). Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiry. Educational Technology Research and Development, 29(2), 75-91.

Gurung, R. A., Chick, N. L., & Haynie, A. (2009). Exploring signature pedagogies: Approaches to teaching disciplinary habits of mind. Stylus Publishing

Ham, J., & Schueller, J. (2012). Signature pedagogies in the language curriculum in Exploring More Signature Pedagogies: Approaches to Teaching Disciplinary Habits of Mind ; edited by Nancy Chick, Aeron Haynie and Regan Gurung. Stylus.

Hodges, C. B., Moore, S., Lockee, B. B., Trust, T., & Bond, M. A. (2020). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning

Huberman, A. M., & Miles, B. M. (2002). Qualitative researcher’s companion. Sage.

Illmer, A., Wang, Y., & Wong, T. (2021, January 22). Wuhan lockdown: A year of China’s fight against the Covid pandemic. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-china-55628488

Kam, C.C.S., & Meyer, J.P. (2015). How careless responding and acquiescence response bias can influence construct dimensionality: The case of job satisfaction. Organizational Research Methods, 18(3), 512-541. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428115571894

Kebritchi, M., Lipschuetz, A., & Santiague, L. (2017). Issues and challenges for teaching successful online courses in higher education: A literature review. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 46(1), 4-29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047239516661713

Krishnan, I. A., Ching, H. S., Ramalingam, S., Maruthai, E., Kandasamy, P., Mello, G. D., Munian, S., & Ling, W. W. (2020). Challenges of learning English in 21st century: Online vs. traditional during covid-19. Malaysian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities (MJSSH), 5(9), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.47405/mjssh.v5i9.494

Krueger, R. A., & Casey, M.A. (2014). Focus Groups: A practical guide for applied research (5th ed.). Sage Publications.

Levy, M. (2009). Technologies in use for second language learning. The modern language journal, 93, 769-782. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2009.00972.x

Lozano, A. A., & Izquierdo, J. (2019). Technology in second language education: Overcoming the digital divide. Emerging Trends in Education, 2(3), 52-70.

MacIntyre, P. D., Gregersen, T., & Mercer, S. (2020). Language teachers’ coping strategies during the COVID-19 conversion to online teaching: Correlations with stress, wellbeing and negative emotions. System, 94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102352

MacKinnon, G. & MacLean, T. (2021). Adapting to leadership in offshore schools: A case study of Sino-Nova Scotian Schools. International Journal of Education Policy & Leadership 17(1), 1-30. https://journals.sfu.ca/ijepl/index.php/ijepl/article/download/1057/287

MacKinnon, G., & Shields, R. (2020). Preparing teacher interns for international teaching: A case study of a Chinese practicum program. Networks: An Online Journal for Teacher Research, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.4148/2470-6353.1306 https://newprairiepress.org/networks/vol22/iss1/4/

Mishra, P., & Koehler M. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017-1054. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00684.x

Patton, M. (2002). Qualitative research and Evaluation (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

Pazilah, F. N., Hashim, H., & Yunus, M. M. (2019). Using technology in ESL classroom: Highlights and challenges. Creative Education, 10(12), 3205-3212. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2019.1012244

Pegrum, M., & Palalas, A. (2021). Attentional literacy as a new literacy: Helping students deal with digital disarray. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 47(2). https://doi.org/10.21432/cjlt28037

Sari, F. M. (2020). Exploring English learners’ engagement and their roles in the online language course. Journal of English Language Teaching and Linguistics, 5(3), 349-361.

Stringer, E. T., & Aragón, A. O. (2021). Action research (5th ed.). Sage publications.

Sweller, J. (2019). Cognitive load theory and educational technology. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-019-09701-3

Voogt, J., & Knezek, G. (2021). Teaching and learning with technology during the COVID-19 pandemic: Highlighting the need for micro-meso-macro alignments. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 47(4). https://doi.org/10.21432/cjlt28150

Westberry, L., Hornor, T., & Murray, K. (2021). The need of the virtual principal amid the pandemic. International Journal of Education Policy and Leadership, 17(10). https://doi.org/10.22230/ijepl.2021v17n10a1139

Xia, J., Fielder, J., & Siragusa, L. (2013). Achieving better peer interaction in online discussion forums: A reflective practitioner case study. Issues in Educational Research, 23(1), 97-104. https://espace.curtin.edu.au/handle/20.500.11937/13284

Gregory MacKinnon, PhD, is a professor of Science and Technology Education in the School of Education at Acadia University in Nova Scotia, Canada. Serving as Chair of International Practica since 2002 has culminated in the placement and supervision of over 160 teacher interns in China. His international work extends to curriculum development in China and Caribbean nations. Email: gregory.mackinnon@acadiau.ca

Tyler MacLean is the Vice Principal of Henan Experimental High School in Zhengzhou China. He has taught Social Studies and English/Language Arts in China for nine years. His master’s degrees in Curriculum and Leadership are from Acadia University in his native Nova Scotia, Canada. Current research interests include cross cultural pedagogy and leadership, online learning, and curriculum development. Email: tyler.maclean1@gmail.com