Helen J. DeWaard, Lakehead University, Canada

Navigating through the Faculty of Education as a teacher educator in Canada is complex and complicated. Research literature calls for an intentional focus on media and digital literacies, and technological competencies, in teacher education. Program directions are confounded by technological trends emerging in kindergarten to grade twelve education and higher education. This post-intentional phenomenological research study examined moments, materials, and insights from the stories shared by participants as they revealed media and digital skills, fluencies, competencies, and literacies in their open educational practice. This research provides insights into how teacher educators seize opportunities to work through complex matters while applying technology resources. It is becoming ever more important to share expertise as practitioners, researchers, and theorists in the field of education by making explicit what is often tacit and unspoken, and when sharing knowledge, reflections, and actions. By actively thinking-out-loud through blogs, social media, and open scholarly publications, educators can openly share details of what, how, and why they do what they do. Research findings reveal the importance of media and digital literacies in the dimensions of communication, creativity, connections, and criticality within an open educational practice as a teacher educator.

Keywords: Canadian, digital technology, faculties of education, open educational practices, teacher educators

Il est complexe et compliqué de se familiariser avec les attentes de la Faculté d’éducation en tant que formateur d’enseignants au Canada. La littérature scientifique relative à la formation des enseignants invite à mettre l’accent sur les compétences médiatiques et numériques, ainsi que sur les compétences technologiques. Les orientations du programme sont dictées par les tendances technologiques qui se dessinent dans l’enseignement de la maternelle au secondaire, ainsi que dans l’enseignement supérieur. Cette étude phénoménologique post-intentionnelle s’est penchée sur des moments, du matériel et des idées que les participants ont partagés dans le cadre de leur pratique éducative libre, ce qui a permis de révéler leurs aptitudes, compétences et niveau de littératie médiatiques et numériques. Cette approche permet de comprendre comment les formateurs d’enseignants se saisissent des ressources technologiques pour aborder des questions complexes. Il devient de plus en plus important de partager l’expertise des praticiens, des chercheurs et des théoriciens dans le domaine de l’éducation, car cela révèle souvent ce qui est tacite et non-dit, et permet de partager des connaissances, des réflexions et des actions. Le fait de réfléchir à chaud grâce aux blogues, aux médias sociaux et aux publications savantes ouvertes est une façon pour les éducateurs de partager ouvertement ce qu’ils font, comment et pourquoi ils font ce qu’ils font. Les résultats de notre étude révèlent l’importance des compétences médiatiques et numériques en matière de communication, de créativité, de connexions et d’esprit critique au sein de la pratique éducative libre de formateurs d’enseignants.

Mots-clés : Canadiens, technologie numérique, facultés d'éducation, pratiques éducatives libres, formateurs d’enseignants

Navigating through teacher education programs in Canada is complex and complicated. For those who teach in faculties of education, competing demands include higher education policies as well as education mandates from provincial sectors for kindergarten to grade twelve curriculum. Additionally, faculty of education program directions are confounded by technological trends emerging in both higher education and the K-12 sector. When considering digital literacy, there are frequent calls from business and industry for a nationwide, cohesive strategy (Hadziristic, 2017). Contributing to this are the growing demands at both the national and global levels for digitally proficient students and educators (McAleese & Brisson-Boivin, 2022; McLean & Rowsell, 2020; UNESCO, 2022, 2023). These pressures and tensions in teacher education are exacerbated with issues of fiscal restraint and the aftermath of pandemic-influenced, technology-driven teaching and learning constraints (Danyluk et al., 2022).

Goodwin and Kosnik (2013) suggested a need for research into how teacher educators perform. Research recommended a closer examination into what it means to be a teacher educator (Ellis & McNicholl, 2015). Now it becomes ever more important that teacher educators share their expertise as practitioners, researchers, and theorists, making explicit what is often tacit and unspoken, when sharing knowledge, reflections, and actions (Beck, 2016; UNESCO, 2022). By enhancing open educational practices (OEPr), teacher educators may showcase what they know, and how they enact and embody the art and craft of teaching (Marzano, 2007). Teacher educators who model OEPr respond to Canada’s Digital Charter: Trust in a Digital World (Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, 2023) and further the mission of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) 2030 Global Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) for education (Montoya, 2018). Specifically, this research furthers the work toward SDG goal 4.c.1 by responding to the global need to substantially increase the number of qualified and trained teachers, as well support international cooperation for teacher training potentially through the sharing of OEPr (Montoya, 2018).

Research literature suggested a need for an intentional focus on media and digital literacies and technological competencies in teacher education (Falloon, 2020; Foulger et al., 2017). This post-intentional phenomenological research study responded to this need by examining moments, materials, and insights from the stories shared by teacher educators in faculties of education across Canada as they reveal media and digital skills, fluencies, competencies, and literacies in their OEPr. By studying the phenomenon of OEPr, insights are gained into how teacher educators seize opportunities to work through complex matters while applying technology resources. By actively “thinking out loud” through blogs, social media, and open scholarly publications, teacher educators share details of the what, how, and why they do what they do.

As revealed in this paper’s findings, the rationale and definition of terms relating to the research are outlined, and conceptual frameworks are identified, before sharing stories from the participants. Insights are provided in the discussion, followed by implications, recommendations, and a conclusion.

Understanding terminology is critical. A clarification of the term practice is offered since this research focussed on the practices of practicing in a teacher educator’s practice. Confusion can and does emerge from this polysemous term as it holds multiple meanings as both a noun (the thing we call a practice) and a verb (the actions we undertake as we practice). Complications occur when the thing is confused with the doing. This research examined how teacher educators practice their craft of teaching within an OEPr.

Education in Canada is a provincial mandate; thus, teacher education falls under provincial dictates and constraints. For purposes of clarity, initial teacher education refers to components in a faculty of education program of study that includes the compilation of courses focusing on preparing students to become teachers in the K-12 sector. Teacher educators and their students are required to bridge the significant differences in teaching and learning between K-12 and higher education. Additionally, technologies and digital resources used in the K-12 sector may not be available to the higher education environments where the learning occurs. This confusion across jurisdictions leaves digital skills, fluencies, and competencies within Canadian faculties of education in a complex tangle.

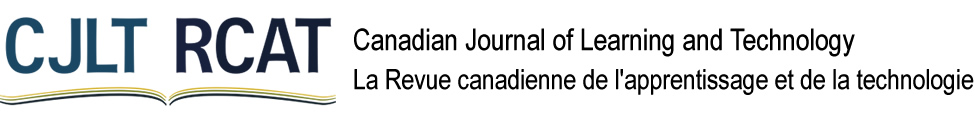

For this research, the acronym OEPr was used to distinguish this concept from research into open pedagogies. This small shift in the commonly used nomenclature within the field of open education provides distinction and clarity (DeWaard, 2023). Definitions of OEPr vary, but for this research OEPr is considered as both external actions or events as well as internal qualities that are contextual, complex, and individual (Cronin, 2017). Open educational practices can include teaching designs, content, and assessment, but also technologies, sociality, community, and cognition (Figure 1). Because open educators use a variety of social media and web-based publication options, objects, and events, their OEPr may be integrated into course materials, referenced in teaching events, and remixed by others.

Figure 1

I Teach

Note. Referencing Palmer (2017); Foulger et al. (2017); Banner and Cannon (2017). Created using Procreate on iPad. Published under CC BY DeWaard (2023).

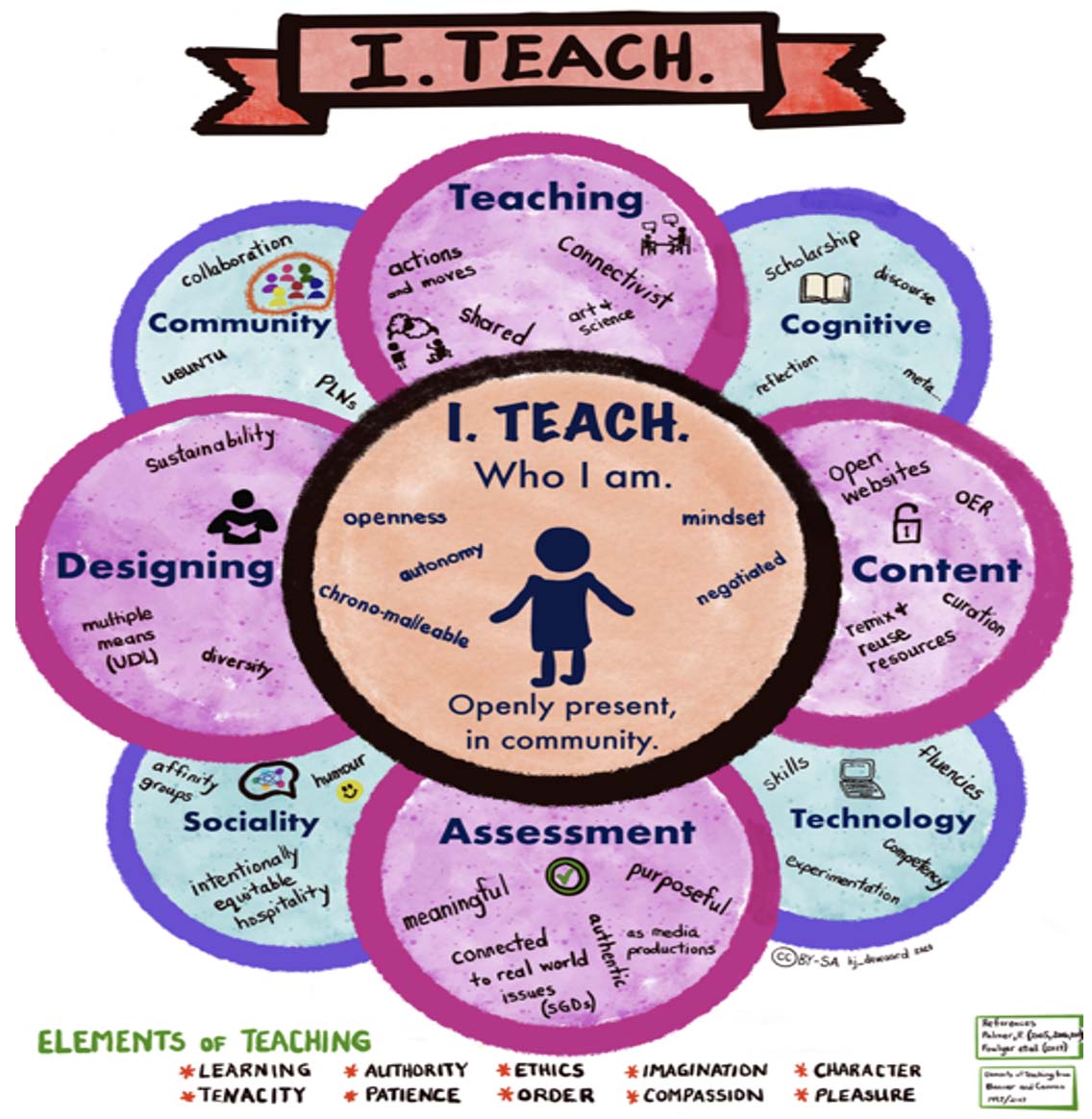

Defining media literacies includes actions of co-construction within social contexts, examining semantics relating to mediums used, understanding contextual media messages, challenging bias and dominant hierarchies, revealing purposes of media messages, and viewing media cultures as sites of struggle (Kellner & Share, 2019). Media literacies are shaped by an understanding of the key areas of text, production, and audience as framed in the remix of the media triangle (Association for Media Literacy, 2022) (Figure 2). For text production, media choices include codes, genres, and commodities. For media production, consideration is given to the tools, technologies, or design factors that shape the messages being communicated. When analyzing or creating media messages within faculty of education courses, consideration includes the audience through distribution factors, technological choices, and control of the production.

Figure 2

Media Triangle Remix

Note. Referencing Association for Media Literacy (2022). Created using Procreate on iPad. Published under CC BY DeWaard (2023).

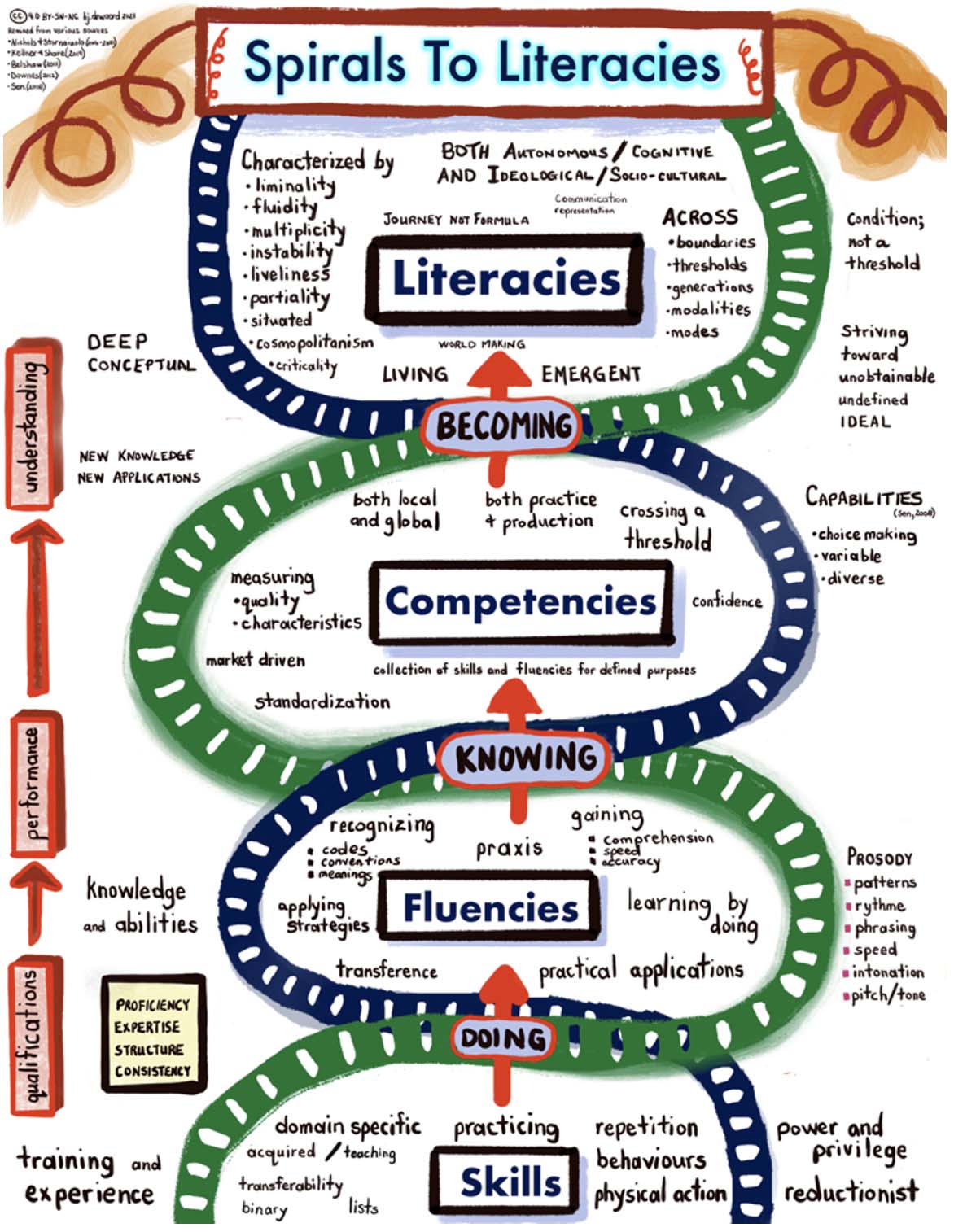

Digital literacies are critical to the inclusion of technologies into teacher education course contexts. Digital literacies are framed by both the cognitive and social practices when using, understanding, and creating with digital technologies (Falloon, 2020; Stordy, 2015). For this research, digital literacies are composed of three areas of proficiency: “the skills and ability to use digital tools and applications; the capacity to critically understand digital media tools and content; and the knowledge and expertise to create and communicate with digital technology” (emphasis in original) (Hoechsmann & DeWaard, 2015, p. 8). By spiralling toward the ideal of digital literacies, teacher educators can acquire digital skills, fluencies, and competencies (Figure 3) that support their OEPr.

Figure 3

Spirals Toward Literacies

Note. Compiled and remixed from Belshaw (2011); Downes (2012); Hoechsmann and Poyntz (2017); Kellner and Share (2019); Nichols and Stornaiuolo (2019, 2021); Smith et al. (2018); Stornaiuolo and LaBlanc (2016); Stornaiuolo et al (2017). Published under CC BY-SA-NC DeWaard (2023).

This research is framed by a socio-constructivism epistemology and a post-intentional phenomenological approach. It also considers the phronesis/episteme dichotomy inherent in the design and delivery of faculty of education programs. The theoretical foundations of socio-cultural constructivist theories of learning originated with Dewey (1916), Vygotsky (Lowenthal & Muth, 2009; Roth & Lee, 2007), and Papert and Harel (1991). A socio-constructivist paradigm adopts a relativist ontology, suggesting there are many possible realities, and a subjectivist epistemology whereby the researcher and participant co-create shared understanding (Denzin & Lincoln, 2013). In this research, the understanding of lived experiences within an OEPr is constructed, action-oriented, acquired through collaborations in conversation, and generated through media/digital processes and productions.

The dichotomy between phronesis and episteme impacts this research as it delves into the understanding of what it means to practice a teaching practice openly. Underlying the shared stories of the participants’ lived experiences are conceptual frameworks of theory-into-practice, practice-into-theory, and theory-and-practice (Russell et al., 2013). When exploring the media and digital literacies of teacher educators who model an OEPr, it is essential to consider the “epistemology of practice that takes fuller account of the competence practitioners sometimes display in situations of uncertainty, complexity, uniqueness, and conflict” (Russell et al., 2013, p. 15). Through sharing their OEPr, reflective practice, and teach-aloud activities, the tacit knowledge implicit within patterns of action of these teacher educators may reveal judgements, skills, and competencies (Russell et al., 2013). Both the theoretical foundations and practical experiences of the participants emerged. It is through practical applications of media and digital skills, fluencies, competencies, and literacies into an OEPr that theoretical understanding can be gained.

Frameworks from the literature relevant to media and digital literacies that supported this research included UNESCO’s Media and Information Literacy framework (2013), MediaSmarts (n.d.), the Digital Literacy framework (Belshaw, 2011), the Digital Literacy Competency Frameworks Analysis (Martínez-Bravo et al., 2022), the DigComp EDU (Redecker, 2017), and the DQ Institute (n.d.). The open education framework Practical Guidelines on Open Education for Academics (Inamorato dos Santos, 2019) also informed the results.

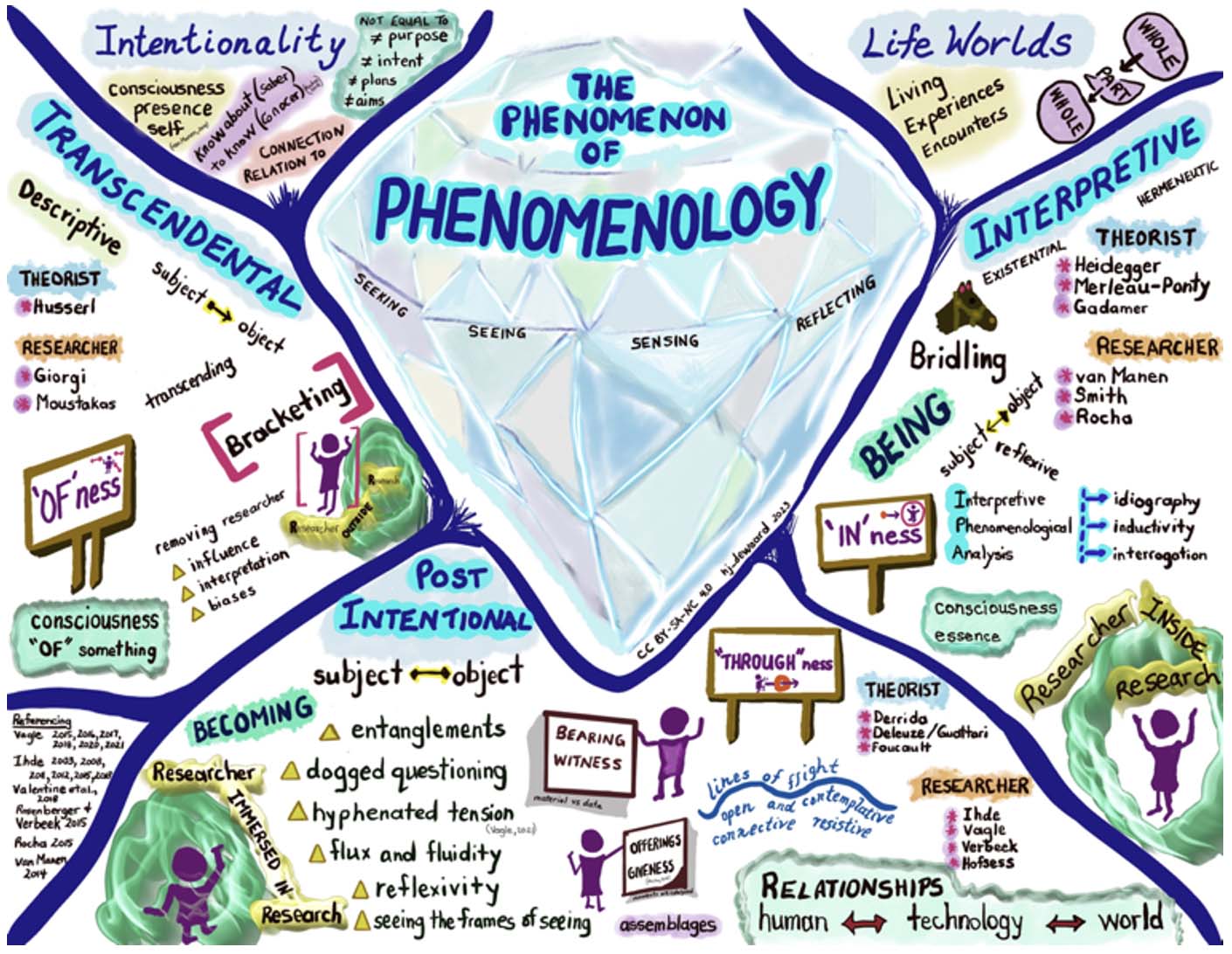

Phenomenological research aims to reveal and describe lived experiences in order to gain understanding of the meaning of a phenomena (Cilesiz, 2011). This post-intentional phenomenological research focuses on “richly describing the experiential essence of human experiences” (Tracy, 2020, p. 65) relating to the OEPr of teacher educators. Post-intentional phenomenology is distinguished from transcendental and interpretive theoretical approaches (Figure 4). As a research methodology, post-intentional phenomenology brings a fluid focus on human-technology relations by examining the ways technologies impact relationships between human beings and the world, thus shaping human interactions, relationships, and embodiment (Ihde, 2011). Following a post-intentional phenomenological approach, this research examined the lived experiences of teacher educators’ relationality (lived relation), corporeality (lived body), spatiality (lived space), temporality (lived time), and materiality (lived things and technologies) (Vagle, 2018). The researched centred on the phenomenon of an OEPr.

Figure 4

The Phenomenon of Phenomenology

Note. Remixed from Ihde (2015); Rocha (2015); Rosenberger and Verbeek (2015); Vagle (2018); Valentine et al. (2018); van Manen (2014). Published CC BY-SA-NC DeWaard (2023).

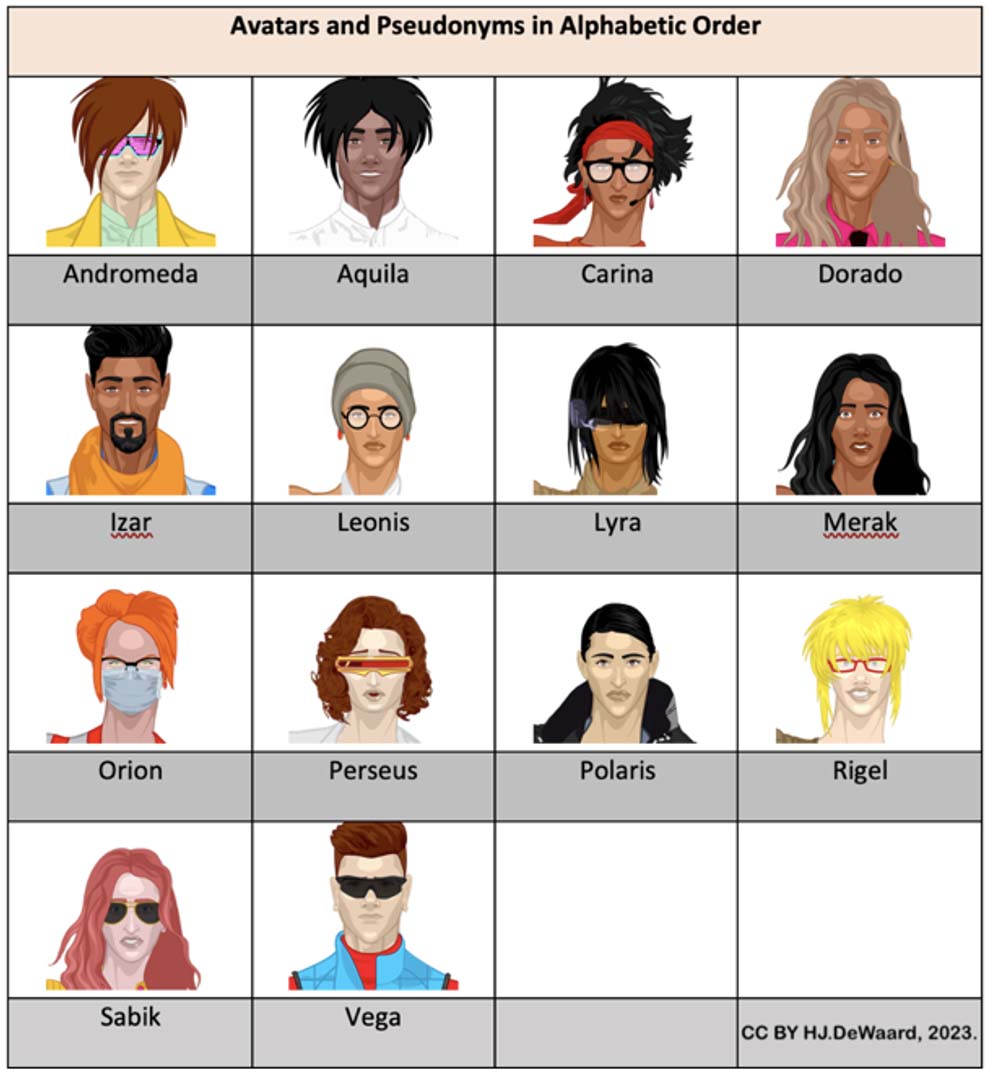

Through purposeful sampling, participants who met the established criteria were contacted. Once informed consents were received, and to ensure confidentiality, randomized avatars and names garnered from star charts were applied (Figure 5) to the 14 participants. Sources of digital information included social media activities, websites, blog posts, course syllabi, and curriculum vitae. The semi-structured and conversational 60-minute interviews followed guidelines outlined by Merriam and Tisdell (2015) and focused on the participants’ lived experiences of media and digital literacies from within their OEPr. Digital artifacts were created by participants after the interviews as reflections of experiences with media and digital literacies. Once transcribed, the data was coded and analyzed using NVivo software to reveal facets that shaped insights. After several reviews of the data, specific elements crystallized into findings (DeWaard, 2023). The findings focus on the shared stories of OEPr relating to teacher educators’ practices. These findings are not intended to be generalizable but are offered as potential practical models to shape media and digital literacies infused with technologies from a teacher educator’s perspective.

Figure 5

Avatars and Pseudonyms

Note. Compiled and remixed from research design and findings. Published under CC BY-SA-NC DeWaard (2023). Anonymized names and images for the participants in this research.

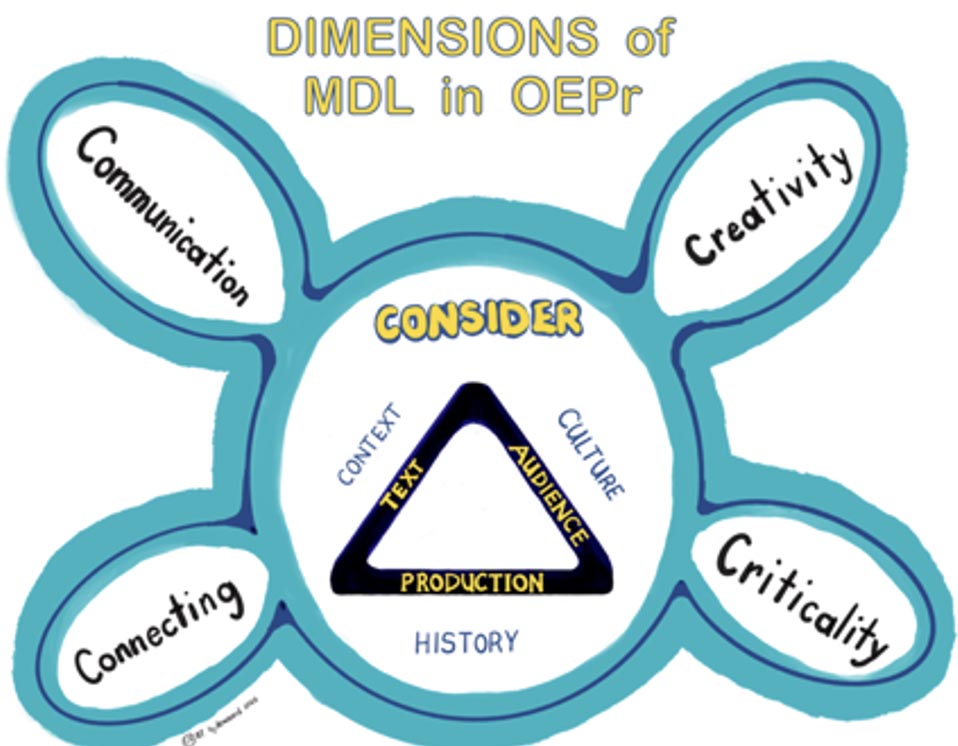

The research findings focus on how the participants managed to keep their eye on their OEPr within an unknown future in uncertain times when infusing media and digital literacies into their teaching, particularly when using technology. Since this research was conducted in the aftermath of COVID-19 constraints and periods of online-only instruction, pandemic related experiences emerged as a sub-plot within the stories. The findings revealed complex navigations and decisions with media and digital skills, fluencies, competencies, and literacies within an OEPr, as mediated through technological integrations. Four dimensions were generated from the shared stories. These include communication, creativity, connections, and criticality (Figure 6). The findings and discussion are merged to better understand how these four dimensions were integrated in the research findings and the literature. To distinguish participants from research literature, the names of participants are designated with bold and italic text.

Figure 6

Dimensions of Media and Digital Literacies (MDL) in Open Education Practice

Note. Compiled and remixed from research findings. Published under CC BY DeWaard (2023).

In the area of communication, participants mentioned risks and benefits, intended audience, and issues of access when communicating with technologies. Participant Merak considered the risk-benefit tensions that emerged when considering safety, security, privacy, and permissions: “I guess my desire to have students live, sharing in the open in my course and finding there was a bit of tension for me in terms of protecting them, just making sure that they were feeling safe enough”. Orion’s and Rigel’s experiences with trolling (when others’ online comments are intended to be negative or hurtful) and Aquila’s experiences with catfishing (when personal images or information are used by others to create fictional or alternative online accounts) showed an awareness of the darker side of technology. Participants mentioned explicitly teaching students about password protection of pages and posts on a blog site, thus ensuring students had agency and control of permissions to sensitive or confidential information published to the web. These experiences modelled care and concern for both their own and students’ data management skills.

When sharing communications as part of an OEPr, Vega wondered: “I'm hired as an educational researcher, a theorist. I'm supposed to be working on behalf of Canadian citizens. So how can I create communication ecosystems so that they can access some of the work?”. For Rigel this suggested that “the purpose that you're doing it is not just performative for the whole world that you actually are doing it because students will feel the value”. For Vega this meant recognizing audience: “If we're talking about access, I think you need to recognize audiences you are trying to communicate with, and then how accessible in terms of having open access is what you're trying to communicate”. Lyra suggested keeping audience in mind when making critical decisions about “what you're comfortable sharing and what you're not comfortable sharing”.

Communication included issues relating to access, specifically entry points and gateways, as well as an intentionality in sharing. Polaris suggested a consideration for using teaching resources that are “visible you know, not behind paywalls” and their avoidance of using technologies “that require students to sign up”. For Andromeda and Merak this meant that learning opportunities were open to “people outside of your class, outside of that specific group would also have access and it's something that you would allow people to share”. Seven participants reflected on how communication, particularly for their students, needed to extend beyond the physical classroom. Issues of access for three participants emerged when using languages other than English.

The findings from the communication dimension reflected the ubiquitous nature of using technology when sharing communications. One participant suggested that media framed the messages, and that digital was the mechanism for sharing communications. The medium, and the digital format of the technologies used, shaped the messages that were communicated and exerted influence over how messages were constructed and shared. Decisions about sharing course materials on open web-based locations was dependent on multiple factors such as the course topic, fluencies with web publication, time required, and supports available for course development and design.

As echoed in this research, digital competencies emphasize communication when educators incorporate “learning activities, assignments and assessments which require learners to effectively and responsibly use digital technologies for communication, collaboration and civic participation” (Redecker, 2017, p. 23). Young and Nichols (2017) suggested that “diversification of communication within teaching and learning practice gives students more choice and opportunity to interact with both their peers and teaching staff” (p. 345). This variation was evident as participants described using blogging as a means of shifting course communications into open digital spaces, using podcasts to deliver course content, and integrating video and image production into their communication strategies with students.

Participants’ communications hinged on decisions to use both digital and analog domains. Continual negotiations between/among distribution of communications through public, private, and controlled digital spaces was evoked. Although technology was ubiquitous to the participants’ practice, the digital was not magic. It permeated the way they practiced teaching and learning. The participants made strategic decisions as they attempted to answer questions such as: Will I share?; Why will I share?; With whom should I share?; Where will I share?; Is this good enough to share?; or How might sharing impact my digital persona? (Cronin, 2017).

Creativity was mentioned by every participant and connected to multimodal productions and performance for themselves and their students. Izar wondered “if you're thinking about open practices, you might be thinking about, you know, how can we enable creativity? How can we let people stand on their own and make choices around what they're learning and how it's represented?” Izar developed teaching materials supported by fair dealing, Creative Commons, and open resources. For Dorado, creativity meant resisting the use of exemplars in course materials or assignments and providing less choice since “if you choose something that's really flexible, then there's more creativity inside of that narrow choice”.

Creativity for many of the participants included accessing, using, and creating within multimodal digital and media productions that incorporated or apply text, icon, image, audio, video, and graphic formats. For Aquila this meant “understanding how to convey messages, through media in different ways, not just print literacy ... we have to be much more well-rounded”. Andromeda and Rigel mentioned multimedia as an entry or gateway into learning, thus synergistically using “what we need to use in order to learn”. For Polaris creativity with multimodal productions “became a real opportunity into building my ability to create using digital tools, which then became the driving force for further deepening my media and digital literacies, which became more apparent and necessary as sharing became possible”. It was through the active process of creating a learning object or designing a course using a variety of media, in concert with developing explicit instruction and critical questioning, that media and digital literacies impacted the participants’ OEPr.

Creativity in OEPr for Sabik and Rigel included consideration of how students were given options to share their learning beyond the “disposable assignment”, described by Wiley (2013) as those tasks such as essays or exams that add no value to the world since they are thrown away and forgotten once they are completed. Rigel provided choice as a gateway “for students to become more open about how and where they share their learning”. Aquila saw creative works, particularly remix, as a core element in their teaching: “I don't have students create essays, I figured by the time they're in my course, they know how to do essays. So, we always explore media. For example, students reflect and create multimodal summaries of learning”. Creativity included choice in how and why they shared, as suggested in Rigel’s comment: “sharing your process is a form of open pedagogy for me; I feel there’s a spectrum of sharing more broadly and making it accessible for a broader audience is really helpful”.

Creative production was not just for the purpose of sharing beyond a course. Perseus questioned “when students create content that they share openly online (e.g., websites, digital artifacts, SM posts, accounts, channels) are their interests as learners served ?” The challenge in creative productions was ensuring authenticity in the process and products — the content, the conversations, the assignments, and the learning activities — and ensuring these meaningfully related to a course of study.

The findings suggested that creativity was an essential element of an OEPr and emerged from a flexible and technologically fluent mindset (Henriksen & Cain, 2020). This fluency in mindset was grounded in disciplinary knowledge, technological knowledge, an experimental disposition with technologies along with a “willingness to push students to consider and re-consider what they know” (Henriksen & Cain, 2020, p. 177). This included a readiness to imitate and remake media (Hobbs & Friesem, 2019), as modelled by Polaris in their digital artifact created using Twine (https://twinery.org/), or to integrate a design approach for a student blog hub for course assignments. Henriksen and Mishra (2015) suggested that teachers who actively cultivate a creative mindset in their teaching practices transfer these creative tendencies from outside, open pursuits and interests, into their teaching practices. This was evident when Andromeda and Lyra shared stories about creating an open Pressbook with their students.

Participants showcased that “students need to engage with issues of production, language, representation, and audiences to address how meaning operates in the electronic media” (Hoechsmann & Poyntz, 2017, p. 7). This was evidenced in Dorado’s lived experiences with students creating assignments relevant to global and urban perspectives in education using Padlet technology and the lived experiences of participants with students who created digital portfolios.

Belshaw (2011) contended that creativity was a necessary component of literacy and suggested that reproduction and remix are creative acts. This was echoed by Hoechsmann (2019) who asserted that the “spark of originality, creativity and ‘authorship’ lies in the yoking together of already existing elements, often with some further innovation or addition” (p. 95). From the findings, one example that specifically points to this remix creativity in action was the story of Carina’s work with teacher candidates and students in local schools to remix coding and computational thinking opportunities within a special project to design and program a robot to navigate on the moon.

Shared stories revealed how participants connected ideas, people, and teaching in ways that built on the shared learning of/with others, particularly with insights gained from COVID-related teaching experiences. Connections included opening up links to others in complimentary fields of study for themselves and their students, as exemplified by Aquila’s comment: “It's really about connecting with expertise in different ways and showing students that they can connect not just to databases and resources online but can connect to the people behind them”. Aquila and Lyra mentioned that they reached out to authors of research papers to build on the ideas presented by these other scholars: “I think we need that connection with experts, you know, or things that we know work and in different ideas, not the same ideas ... as we already had”. When knowledge sharing, Izar made efforts to “try to make outputs open, try to make as much of the teaching as possible, open, because it can have effects that are interesting, if you make a connection with another educator”.

Connections were shaped by building trusting relationships. Dorado mused:

I think that whether it's between teachers and students, or researchers and participants in online spaces with distant others that you may never ever see in person, I think that kind of relational work has to happen, especially if you're doing critical literacy work, because you've got to have a lot of trust.

Additionally, Dorado reflected that relationship building required active listening along a continuum from short term contacts to deeper connections. For Aquila this linked back to experiences and relationships developed over time, where geographic locations mattered less and maintaining relationships mattered more: “I guess the idea that we're better together, that our voices matter from any place that we can find, we can build closer relationships with people that we don't necessarily know, that's the strength of weak ties”. Meaningful connections in an OEPr are supported by digital technologies and media productions, both individual and collaborative.

From these findings, participants’ stories reveal how humanizing teaching and learning practices engaged others through the screen rather than to the screen (Morris, 2020). For Vega, this relationship work required “unconditional hospitality” and recognizing “that when you're a guest in someone else's space, then there's certain roles and responsibilities. But also, when you're hosting a guest, there's roles or responsibilities. So that relationship between guests and hosts, it goes back and forth”. Vega described unconditional hospitality as being attuned and deeply listening to others, being reciprocal, sharing accessibly, understanding the barriers preventing connections, and avoiding inflicting harm on others. Connectedness is described in how participants formed hybrid identities to exchange “needs, motivations, solve problems or to create new products/ideas” (Martínez-Bravo et al., 2022, p. 6).

Thestrup and Gislev (Mackenzie et al., 2022) suggested that acting globally and feeling connected required a mindset found on the playground. Such playful mindsets included “experimental, non-linear, immediate and multimodal digital literacy practices” linking to “content, tools of learning, contexts, peers, levels of challenge, time and place” (Tour, 2017, p. 15). This playful ethos was evident in the participants’ stories as they uncovered connections from/to texts, self, and the world within nuanced and multiple layers of engagement, while maintaining a focus on their students as the primary audience. This was modelled in the use of course hashtags and through purposeful collaborations on productions with/for student learning such as Leonis’ connections to global contexts through video productions with immigrant students, and Andromeda and Izar’s connections to the Global OER Graduate Network (GO-GN).

Participants’ interactions through the screen were marked by a heightened awareness of endeavours to dismantle power dynamics, as reflected in the research literature (Couros & Hildebrandt, 2016; Mirra, 2019). Participants applied approaches within their OEPr to cultivate relationships and structure opportunities to build connections that included sharing, reuse, and remix of materials and methods to break down hierarchical structures and open connections with/for students. The shared stories included descriptions of active and sometimes playful engagements in course work, communities of practice, and networked learning.

As suggested by Bell Hooks (2010), criticality requires thinking in action, interactive processes, becoming relentless interrogators, and keeping an open mind. Criticality for the participants and their students occurred in how they received and emitted information, as they constructed professional digital identities and circulated their learning into open digital spaces.

Perseus mentioned: “I have the little open access symbol on my CV, and I put it beside every single publication on my CV; any of them that are open access, I ensure that that symbol is there”. Participants’ stories included facing fears and accepting the risks of openly sharing as a teacher educator, as exemplified in Andromeda’s comment: “it's not just about I'm scared to share. It's I'm scared to share because of professional repercussions, which is very different.” Criticality was evident in experiences with their students as the participants supported teacher candidates to reveal their professional identities in open web-based spaces. Consideration for “this practice of helping teachers to sort of grow into their digital public persona through, you know, open writing” was mentioned by six participants.

Criticality was noted by Andromeda who mentioned sharing as “a negotiation and co-design between an instructor and the student to support their learning pathway on their learning journey”. From Merak’s experiences, criticality was an essential and core tenet “because any instance in which we see technology as neutral as not having been socially constructed and not constructing us, I believe to be problematic”. Dorado wondered: “I guess where the critical part comes, is partly about the tool, but really more about the content, right? And the kinds of ideas that are in there.” Leonis suggested: “media literacy is more of critiquing things. I mean, it is supposed to be productive. But I don't think it's been all that productive. The digital allows you to take it into that productive space with a critical perspective”.

From these findings, criticality emerged through careful, collaborative, and informed critique of technologies, structures, and participation. Criticality explicitly included examination of their own practice and that of organizational decision-makers. Participants mentioned intentional actions to counter techno-deterministic educational technology narratives, particularly the notion of knowledge scarcity (Stewart, 2015). Similarly, Perseus mentioned resisting attentional economies with its focus on clicks and time on task.

Participants shared their intentional decisions to oppose the academic surveillance of students (Kuhn & Raffaghelli, 2022) and contested referencing students as consumers (Mirra et al., 2018), as evident in Perseus’ comments of technological architectures that embed market logics to perpetuate attentional economies and Rigel’s questions about platform capitalism. For Izar and Orion this criticality included decisions relating to tools and technologies for the curation and aggregation of student work with a view toward technological agnosticism.

The criticality dimension included how OEPr contributed to the establishment or breaking of boundaries relating to identity and power structures (Koseoglu, 2017; Stewart, 2021), and criticality in data literacies and algorithmic bias (Nichols et al., 2021; Raffaghelli & Stewart, 2020). Criticality was evident as participants revealed how they grappled with ethical use, creation, and communication of media produced with digital technologies, but more worrisome were those productions by technologies which occurred with the advent of increasingly capable artificial intelligence software (Borenstein & Howard, 2021), particularly with large language models such as ChatGPT (Contact North, 2023). As mentioned by Aquila, additional shifts in OEPr may emerge as the application of block-chain technologies impact educational practices (Privacy Technical Assistance Center, 2019). This reflects notions of criticality as a digital literacy since it “constitutes a great commitment to the construction of significant ecosystems and the development of an awareness and values connected with social and civic responsibility in a globalized world” (Martínez-Bravo et al., 2022, p. 11).

The findings suggest that criticality within an OEPr involves the creation of spaces for building knowledge that are grounded in the labour of marginalized communities. For Collier and Lohnes-Watulak (Mackenzie et al., 2022) this included interrogating where people in positions of power inadvertently or intentionally erase knowledge work created by others. This is of particular importance to Canadian teacher educators in order to address and respond to issues identified in the Calls to Action (The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2015). Opportunities to remix content and produce multimedia elements in courses in faculties of education may offer students a creative way to show what they know, thus “troubling the traditional definitions of academic authorship and knowledge ... these new forms could validate understandings rooted in communities of colour, indigenous communities, and queer communities” (MacKenzie et al., 2022, p. 310). Opportunities for marginalized populations to share their stories speaks to how faculties of education may shape the way higher education addresses concerns of access, equity, indigeneity, diversity, and marginalization. This echoes how criticality is applied to expressions of social imaginaries, described as the shared collections of artefacts, images, and sounds constituting the representational milieu within which individuals give and receive communicated knowledge (Wallis & Rocha, 2022).

As teacher educators revise course designs in whatever technological, pedagogical, or content areas they teach, they adapt to new and everchanging dictates and evolving digital technologies. This research revealed the complex and complicated decisional and navigational options made by teacher educators when focusing on communication, connections, creativity, and criticality as primary elements within an openly shared educational practice.

This applies to not only their own practice — as they consider how to share their pedagogical expertise and tacit knowledge about subject matter, teaching strategies, or assessment practices — but also student learning within the course design. One example was Vega’s navigations and decisions when using podcasting as a primary means of course content with/for students. Another example was Izar’s , Aquila’s, and Orion’s efforts to provide students with an aggregated blog as a means of connecting and networking while engaging in course related content, pedagogies, and technologies.

Recommendations that emerge from the findings and discussions that are relevant for teacher educators when developing an OEPr, include:

This research identified the need for teacher educators to critically examine and share their teaching and learning expertise with others in local, national, and global contexts. A teacher educator’s OEPr can model and respond to current calls in national and global spaces and places for shared and collaborative teaching materials and practices from teacher education programs around the world (UNESCO, 2023). Infusing media and digital literacies into this OEPr, by focusing efforts on the key dimensions of communication, creativity, connections, and criticality, can better support the complex and complicated navigations teacher educators need to manage within an OEPr in current faculty of education instructional practices, and thus become trusted voices and exemplary models for others to follow.

Association for Media Literacy (AML). (2022). About. Association for Media Literacy https://aml.ca/

Banner, J. M., & Cannon, H. C. (2017). The elements of teaching (2nd ed.). Yale University Press.

Beck, C. (2016). Rethinking teacher education programs. In C. Kosnik, S. White, C. Beck, B. Marshall, A. L. Goodwin, & J. Murray (Eds.), Building bridges: Rethinking literacy teacher education in a digital era (pp. 193-205). Sense Publishing.

Belshaw, D. (2011). What is digital literacy? [Ed.D., Durham University]. https://dmlcentral.net/wp-content/uploads/files/doug-belshaw-edd-thesis-final.pdf

Borenstein, J., & Howard, A. (2021). Emerging challenges in AI and the need for AI ethics education. AI and Ethics, 1(1), 61-65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-020-00002-7

Cilesiz, S. (2011). A phenomenological approach to experiences with technology: Current state, promise, and future directions for research. Educational Technology Research & Development, 59(4), 487-510. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-010-9173-2

Contact North. (2023, January 5). Ten facts about ChatGPT. Teach online. https://teachonline.ca/tools-trends/ten-facts-about-chatgpt

Couros, A., & Hildebrandt, K. (2016). Emergence and innovation in digital learning: Foundations and applications (G. Veletsianos, Ed.). Athabasca University Press. https://doi.org/10.15215/aupress/9781771991490.01

Cronin, C. (2017). Openness and praxis: Exploring the use of open educational practices in higher education. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(5). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i5.3096

Danyluk, P., Burns, A., Hill, S. L., & Crawford, K. (2022). Crisis and opportunity: How Canadian Bachelor of Education programs responded to the pandemic. Canadian Association for Teacher Education (CATE). https://doi.org/10.11575/PRISM/39534

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.). (2013). Collecting and interpreting qualitative materials (4th ed.). SAGE Publishing Inc.

DeWaard, H. (2023). Media and digital literacies in Canadian teacher educators’ open educational practices: a post-intentional phenomenology [PhD Dissertation, Lakehead University]. https://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca/handle/2453/5268

Dewey, J. (1916). Chapter 7: The democratic conception in education. In democracy and education (pp. 85-104). Penn State. http://xroads.virginia.edu/~Hyper2/Dewey/ch07.html

Downes, S. (2012). Connectivism and connective knowledge. National Research Council Canada. https://www.downes.ca/files/books/Connective_Knowledge-19May2012.pdf

DQ Institute. (2021). What is the DQ framework? Global standards for digital literacy, skills, and readiness. [weblog]. DQ Institute Global Standards for Digital Intelligence. https://www.dqinstitute.org/global-standards/

Ellis, V., & McNicholl, J. (2015). Transforming teacher education: Reconfiguring the academic work. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Falloon, G. (2020). From digital literacy to digital competence: The teacher digital competency (TDC) framework. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(5), 2449-2472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09767-4

Foulger, T. S., Graziano, K. J., Schmidt-Crawford, D., & Slykhuis, D. A. (2017). Teacher educator technology competencies. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 25(4), 413-448. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/181966/

Goodwin, A. L., & Kosnik, C. (2013). Quality teacher educators = quality teachers? Conceptualizing essential domains of knowledge for those who teach teachers. Teacher Development, 17(3), 334-346. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2013.813766

Hadziristic, T. (2017). The state of digital literacy in Canada: A literature review. Brookfield Institute for Innovation + Entrepreneurship. https://brookfieldinstitute.ca/wp-content/uploads/BrookfieldInstitute_State-of-Digital-Literacy-in-Canada_Literature_WorkingPaper.pdf

Henriksen, D., & Cain, W. (2020). Creatively flexible technology fluent–Developing an optimal online teaching and design mindset. In S. McKenzie, F. Garivaldis, & K. R. Dyer (Eds.), Tertiary online teaching and learning (pp. 177-186). Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-8928-7

Henriksen, D., & Mishra, P. (2015). We teach who we are: Creativity in the lives and practices of accomplished teachers. Teachers College Record, 17(070303), 1-46. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811511700708

Hobbs, R., & Friesem, Y. (2019). The creativity of imitation in remake videos. E-Learning and Digital Media, 16(4), 328-347. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042753019835556

Hoechsmann, M. (2019). Pedagogy, precarity, and persuasion: The case for re/mix literacies. The International Journal of Critical Media Literacy, 1(1), 93-101. https://doi.org/10.1163/25900110-00101008

Hoechsmann, M., & DeWaard, H. (2015). Mapping digital literacy policy and practice in the Canadian education landscape. Media Smarts Canada. http://mediasmarts.ca/sites/mediasmarts/files/publication-report/full/mapping-digital-literacy.pdf

Hoechsmann, M., & Poyntz, S. (2017). Learning and teaching media literacy in Canada: Embracing and transcending eclecticism. Taboo: The Journal of Culture and Education, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.31390/taboo.12.1.04

Hooks, Bell. (2010). Teaching critical thinking: Practical wisdom. Routledge.

Ihde, D. (2011). Stretching the in-between: Embodiment and beyond. Foundations of Science, 16(2-3), 109-118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10699-010-9187-6

Ihde, D. (2015). Positioning postphenomenology. In R. Rosenberger & P. P. Verbeek (Eds.), Postphenomenology investigations: Essays on human-technology relations (pp. vii-xvi). Lexington Books.

Inamorato dos Santos, A. (2019). Practical guidelines on open education for academics: Modernising higher education via open educational practices (JRC115663). Publications Office of the European Union. https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC115663

Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada. (2023, March 13). Building a foundation of trust. Government of Canada: Canada’s Digital Charter. https://ised-isde.canada.ca/site/innovation-better-canada/en/canadas-digital-charter-trust-digital-world

Kellner, D., & Share, J. (2019). The critical media literacy guide: Engaging media and transforming education. Brill Sense.

Koseoglu, S. (2017, May 16). Boundaries of openness. Completely Different Readings. https://differentreadings.com/2017/05/16/boundaries-of-openness/

Kuhn, C., & Raffaghelli, J. (2022). Report for the project: Understanding data: praxis and politics. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.6482613

Lowenthal, P., & Muth, R. (2009). Constructivism. In E. F. Provenzo Jr. & A. B. Provenzo (Eds.), Encyclopedia of the social and cultural foundations of education (pp. 178-179). Sage Publishing. http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.lakeheadu.ca/10.4135/9781412963992.n86

MacKenzie, A., Bacalja, A., Annamali, D., Panaretou, A., Girme, P., Cutajar, M., Abegglen, S., Evens, M., Neuhaus, F., Wilson, K., Psarikidou, K., Koole, M., Hrastinski, S., Sturm, S., Adachi, C., Schnaider, K., Bozkurt, A., Rapanta, C., Themelis, C., ... Gourlay, L. (2022). Dissolving the dichotomies between online and campus-based teaching: A collective response to the manifesto for teaching online (Bayne et al., 2020). Postdigital Science and Education, 4(2), 271-329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-021-00259-z

Martínez-Bravo, M. C., Sádaba Chalezquer, C., & Serrano-Puche, J. (2022). Dimensions of digital literacy in the 21st century competency frameworks. Sustainability, 14(3), 1867. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031867

Marzano, R. J. (2007). The art and science of teaching: A comprehensive framework for effective instruction. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

McAleese, S., & Brisson-Boivin, K. (2022). From access to engagement: A digital media literacy strategy for Canada. MediaSmarts. https://mediasmarts.ca/research-policy

McLean, C., & Rowsell, J. (2020). Digital literacies in Canada. In J. Lacina & R. Griffith (Eds.), Preparing globally minded literacy teachers (1st ed., pp. 177-198). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429397790-11

MediaSmarts. (n.d.). Digital media literacy framework. Canada’s Centre For Digital Media Literacy. https://mediasmarts.ca/digital-media-literacy/general-information/digital-media-literacy-fundamentals/digital-media-literacy-framework

Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2015). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th ed.). Jossey Bass.

Mirra, N. (2019). From connected learning to connected teaching: Reimagining digital literacy pedagogy in English teacher education. English Education, 51(3), 261-291. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26797038

Mirra, N., Morrell, E., & Filipiak, D. (2018). From digital consumption to digital invention: Toward a new critical theory and practice of multiliteracies. Theory Into Practice, 57(1), 12-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2017.1390336

Montoya, S. (2018, September 12). Meet the SDG 4 data: Indicators on school conditions, scholarships and teachers. UNESCO.Org. http://uis.unesco.org/en/blog/meet-sdg-4-data-indicators-school-conditions-scholarships-and-teachers

Morris, S. M. (2020, December 3). Teaching through the screen. Sean Michael Morris. https://www.seanmichaelmorris.com/teaching-through-the-screen-and-the-necessity-of-imagination-literacy/

Nichols, T. P., & Stornaiuolo, A. (2019). Assembling “digital literacies”: Contingent pasts, possible futures. Media and Communication, 7(2), 14-24. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v7i2.1946

Nichols, T. P., Smith, A., Bulfin, S., & Stornaiuolo, A. (2021). Critical literacy, digital platforms, and datafication. In J. Z. Pandya, R. A. Mora, J. H. Alford, N. A. Golden, & R. S. de Roock, The Handbook of Critical Literacies (1st ed., pp. 345-353). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003023425-40

Palmer, P. J. (2017). The courage to teach: Exploring the inner landscape of a teacher’s life (20th Anniversary Edition). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Papert, S., & Harel, I. (1991). Situating constructionism. http://www.papert.org/articles/SituatingConstructionism.html

Privacy Technical Assistance Center. (2019). What is blockchain? U.S. Department of Education. https://tech.ed.gov/files/2019/06/Blockchain_PTAC_6-19_print.pdf

Raffaghelli, J. E., & Stewart, B. (2020). Centering complexity in ‘educators’ data literacy’ to support future practices in faculty development: A systematic review of the literature. Teaching in Higher Education, 25(4), 435-455. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2019.1696301

Redecker, C. (2017). European framework for the digital competence of educators: DigCompEdu (EUR - Scientific and Technical Research Reports EUR 28775 EN). Publications Office of the European Union. https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/publication/eur-scientific-and-technical-research-reports/european-framework-digital-competence-educators-digcompedu

Rosenberger, R., & Verbeek, P. P. (2015). A field guide to postphenomenology. In R. Rosenberger & P. P. Verbeek (Eds.), Postphenomenological investigations: Essays on human-technology relations (pp. 9-41). Lexington Books.

Roth, W.-M., & Lee, Y.-J. (2007). “Vygotsky’s neglected legacy”: Cultural-historical activity theory. Review of Educational Research, 77(2), 186-232. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654306298273

Russell, T., Martin, A., O’Connor, K., Bullock, S., & Dillon, M. (2013). Comparing fundamental conceptual frameworks for teacher education in Canada. In L. Thomas (Ed.), What is Canadian about teacher education in Canada? Multiple perspectives on Canadian teacher education in the twenty-first century (pp. 10-36). Canadian Association for Teacher Educators. https://cate-acfe.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/What-is-Canadian-about-Teacher-Education-in-Canada-1.pdf

Smith, A., Stornaiuolo, A., & Phillips, N. C. (2018). Multiplicities in motion: A turn to transliteracies. Theory Into Practice, 57(1), 20-28. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2017.1390334

Stewart, B. (2015). In abundance: Networked participatory practices as scholarship. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 16(3). http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/2158/3343

Stewart, B. (2021). The open dissertation: How social media shaped–and scaled–My PhD process. In J. Sheldon & V. Sheppard (Eds.), Online communities for Ph.D researchers: Building engagement with social media. (pp. 8-22). Routledge.

Stordy, P. H. (2015). Taxonomy of literacies. Journal of Documentation, 71(3), 456-476. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/JD-10-2013-0128

Stornaiuolo, A., & LeBlanc, R. J. (2016). Scaling as a literacy activity: Mobility and educational inequality in an age of global connectivity. Research in the Teaching of English, 50(3), 263-287. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24889922

Stornaiuolo, A., Smith, A., & Phillips, N. C. (2017). Developing a transliteracies framework for a connected world. Journal of Literacy Research, 49(1), 68-91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086296X16683419

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission. (2015). Truth and reconciliation commission of Canada: Calls to action. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/british-columbians-our-governments/indigenous-people/aboriginal-peoples-documents/calls_to_action_english2.pdf

Tour, E. (2017). Teachers’ personal learning networks (PLNs): Exploring the nature of self-initiated professional learning online. Literacy, 51(1), 11-18. https://doi.org/10.1111/lit.12101

Tracy, S. J. (2020). Qualitative research methods: Collecting evidence, crafting analysis, communicating impact (2nd ed.). Wiley Blackwell.

UNESCO. (2013). Global media and information literacy assessment framework: Country readiness and competencies. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000224655

UNESCO. (2022). The ICT competency framework for teachers harnessing OER project: Digital skills development for teachers (Programme and Meeting Document CI-2022/WS/4). https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000383206.locale=en

UNESCO. (2023, March 29). UNESCO’s ICT competency framework for teachers. UNESCO. https://www.unesco.org/en/digital-competencies-skills/ict-cft

Vagle, M. D. (2018). Crafting phenomenological research (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Valentine, K. D., Kopcha, T. J., & Vagle, M. D. (2018). Phenomenological methodologies in the field of educational communications and technology. TechTrends, 62(5), 462-472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-018-0317-2

van Manen, M. (2014). Phenomenology of practice. Routledge.

Wallis, P. D., & Rocha, T. (2022). Designing for resistance: Epistemic justice, learning design, and open educational practices. Journal for Multicultural Education, 16(5), 554-564. https://doi.org/10.1108/JME-12-2021-0231

Wiley, D. (2013, October 21). What is open pedagogy? Improving Learning. https://opencontent.org/blog/archives/2975

Young, S., & Nichols, H. (2017). A reflexive evaluation of technology-enhanced learning. Research in Learning Technology, 25(0). https://doi.org/10.25304/rlt.v25.1998

Helen DeWaard teaches online in the Faculty of Education at Lakehead University in Ontario, Canada, and recently completed her Ph.D. in Educational Studies from Lakehead University. She authors and co-authors papers and book chapters on teaching and learning with digital media, assessment, mentoring, and critical literacy. Email: hdewaard@lakeheadu.ca ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8894-2259 Website: https://hjdewaard.ca/