Jennifer Walsh Marr, University of British Columbia, Canada

Shihua Tan, University of British Columbia, Canada

Student readiness for university study cannot be assumed; the progression to become a successful student requires support. Highlighting the implementation of purposeful, accessible, and inclusive pedagogical design, this case study explores emergent academic literacies and community building using social annotation in the context of remote teaching and learning. This study analyses first year international students’ annotations in academic texts for indicators of learning and community in their asynchronous interactions with one another. Findings indicate that students were able to discern relevant aspects of meaning-making within their texts, pointing to developing academic literacies. Student threaded annotations, group work, and peer review demonstrated individual and shared learning developed over sustained engagement with one another. The study provides support for a curriculum that facilitates and supports novice scholar participation in university communities and discourses.

Keywords: academic literacies, community of inquiry, online learning, principles of inclusive pedagogy, social annotation

On ne peut pas présumer que les étudiantes et étudiants sont prêts pour réussir ses études universitaires; leur progression pour devenir des étudiantes et étudiants performants nécessite du soutien. Cette étude de cas met en avant la mise en œuvre d’une conception pédagogique accessible et inclusive, et explore les nouvelles compétences universitaires émergentes et le développement de communauté en utilisant l’annotation sociale dans le contexte de l’enseignement et l’apprentissage à distance. Cette étude analyse les annotations d’étudiantes et étudiants internationaux de première année dans des textes universitaires afin d’identifier des indicateurs d’apprentissage et de communauté dans leurs interactions asynchrones les uns avec les autres. Les résultats indiquent que les étudiantes et étudiants étaient capables de discerner les aspects pertinents de la création de sens dans leurs textes, ce qui indique le développement des compétences universitaires. Leurs annotations, leurs travaux de groupe et l’évaluation par les pairs ont démontré un apprentissage individuel et partagé développé grâce à un engagement soutenu les uns envers les autres. L’étude apporte un appui aux programmes d’études qui facilitent et soutiennent la participation des chercheurs débutants aux communautés et aux discours universitaires.

Mots-clés : compétences universitaires, communauté d’enquête, enseignement en ligne, principes de la pédagogie inclusive, annotation sociale

When students begin university studies, they may need to navigate many new factors of academic life such as where to find information, how best to get through and make sense of readings, and how to engage in class discussions. These are challenges faced by students when they move from high school to university, where they study and work in their native language. These challenges are amplified for students who study in a new country and language. The shift to remote online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic only exacerbated the difficulty for first year students to establish familiarity with academic conventions and their sense of belonging at university (van Heerden & Bharuthram, 2023). In addition to language barriers, international university students faced other challenges, such as different time zones and cultural expectations. Particularly in this context, these challenges were intensified by a lack of face-to-face interaction for acquiring cultural norms and discriminatory practices, despite the increased financial cost (Tavares, 2024).

The course described and studied is a discipline-specific language tutorial and is part of a first-year program for international students at a Canadian university. This cohort program is specifically designed for students who have gained academic entry to the university but have not achieved its English language proficiency standards for direct entry (Zappa-Hollman & Fox, 2021). This cohort of international students is separate from those first-year students who enter the university directly. They complete their year of university studies with a full course load, including an introductory academic writing course and the discipline-specific language analysis course discussed here.

In this program, course instructors draw from readings, lectures, and assessments from students’ disciplinary courses to situate analyses of language in texts and tasks authentic to their studies. For example, students on the science program study how English is used in calculus, physics, earth and ocean science, and computer science. Meanwhile, students on the arts program study how English is used in subjects such as sociology, history, political science, human geography, and psychology.

The curriculum design was influenced by principles of academic literacies to make the disciplinary features of students’ concomitant arts courses more visible and accessible (Lea & Street, 1998; Lillis, 2006; Nallaya et al., 2022; Wingate & Tribble, 2012). This course drew from authentic disciplinary texts to make the connections and applications explicit.

This case study investigates how an online course supported first year, multilingual, international university students by enacting Lowenthal et al.’s (2020) three principles of inclusive and accessible online teaching. Work in academic literacies (Maldoni, 2018; Nallaya et al., 2022; Wingate & Tribble, 2012) was prioritized for the course’s language focus and rationale, and student social annotation of course texts is highlighted here as evidence of their academic and social engagement (Clinton-Lisell, 2023; Kalir & Garcia, 2021; Morales et al., 2022). As a sense of community and belonging are integral to student engagement and success (Walton & Cohen, 2007), ways to mitigate isolation endemic to online learning (Choo et al., 2020; Tavares, 2024), exacerbated by pandemic protocols, were investigated. The research question asks: How did social annotation and stable student groups help students develop their academic literacies and foster community in a remote teaching and learning environment?

This study uses social annotation for both pedagogy and evidence of student interactions. The course design used social annotation to have students engage in individual learning and in small groups, critically examining the meaning behind different disciplinary language and texts. For this paper, we highlight how students’ annotations across the course exemplify their engagement with their nascent academic literacies and with one another.

Literacies are the means of comprehending and engaging in valued ways, varying from context to context. This acknowledges that literacy is not a monolithic concept. Specific to academia, pluralizing academic literacies further acknowledges that different disciplines have different practices indicative of knowledge bases, participants, and power differentials (Lea & Street, 1998; Nallaya et al., 2022; Wingate & Tribble, 2012). While typically represented through language, particularly in academia, multiliteracies are inclusive of other modes of meaning-making, such as sound and imagery, that are also informed by context (Kalantzis et al., 2016). The primacy of context is important, as academic literacies are firmly situated within the social construction of knowledge, gained through exposure, engagement, and participation in literacy practices. When first encountering discipline-specific practices, everyone is a novice, as each discipline has its own configuration of creating and presenting knowledge (Basset & Macnaught, 2024; Wingate & Tribble, 2012). Some proponents of academic literacies advocate for “making language visible” by specifically attending to it (Lillis, 2006, p. 34 as cited in Wingate & Tribble, 2012). This focused attention on language recognizes that mere exposure is insufficient; the ways in which language is used to make disciplinary meaning can seem opaque to novice scholars (Bond, 2020).

A focus on academic literacies emerged in response to the broadening of postsecondary enrolment (Nallaya et al., 2022; Wingate & Tribble, 2012) which was a shift away from the enrolment of mainly the elite white male traditional student who had been groomed for university throughout his schooling (Klinger & Murray, 2012). University enrolment has now expanded to include women, domestic students from different socioeconomic backgrounds, and international students. Each new cohort has different experiences and levels of knowledge and may not have had the same access to the dominant literacy patterns of academia as traditional students. Many multilingual international students require further support to develop English language proficiency (Maldoni, 2018; Nallaya et al., 2022). However, academic literacies are not solely language based, as

learning to write in an academic discipline is not a purely linguistic matter that can be fixed outside the discipline, but involves an understanding of how knowledge in the discipline is presented, debated and constructed. The second issue is that reading, reasoning and writing in a specific discipline is difficult for native and non-native speakers, or, in other terms, home and international students alike. (Wingate & Tribble, 2012, p. 481)

Academic literacies are fostered through social contact and the negotiation of meaning with others. This process can be facilitated through careful design and sustained practice within a learning community that provides a rich, supportive context for novice scholars to navigate disciplinary practices and establish themselves as active participants (Maldoni, 2018; Nallaya et al., 2022). This learning community benefits from accessible and inclusive teaching.

In addition to developing academic literacies, a sense of belonging or “seeing oneself as socially connected” is an important component of navigating new academic contexts successfully (Walton & Cohen, 2007, p. 82). Particularly for non-traditional students, this can be fostered in learning environments that prioritize safety and respect, which engage the whole and authentic selves of participants and that establish a strong community (van Heerden & Bharuthram, 2023; Walton & Cohen, 2007). Studies show that community building can help develop problem-solving skills, communication skills, interdisciplinary learning, and critical thinking, as well as improve academic success and student retention rates (Beers et al., 2021; Nye, 2015; Smith et al., 2009). Community building in higher education is characterized by a student-centred approach that prioritizes collaborative work and active learning online or face-to-face, with benefits to students’ wellbeing, belonging, and academic success (Walton & Cohen, 2007).

Lowenthal et al. (2020) foster belonging and community through inclusive and accessible teaching design manifest through three principles: (1) useable courses and content, (2) inclusive pedagogy and course design, and (3) accessible and inclusive teaching. Originally situated to compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act, Lowenthal et al. take a bold, more inclusive stance advocating for the support of all learners. Furthermore, they expand this alignment with academic literacies to claim, “making learning opportunities accessible to all is not just a legal issue but ultimately an ethical issue” (2020, p. 2).

In expanding upon their first principle of usable courses and content, Lowenthal et al. (2020) argue that the learning management system must be navigable and their content accessible. In describing the second principle of inclusive pedagogy and course design, they adopt the tenets of universal design for learning (UDL): multiple means of engagement, multiple means of representation, and multiple means of action and expression (Centre for Applied Special Technology [CAST], 2018). In essence, this means providing options for learners to choose which aspects of course content to engage with (multiple means of engagement), choice in how they engage (multiple means of representation), and flexibility in how they demonstrate their learning (multiple means of action & expression). Finally, the third principle of accessible and inclusive teaching stresses the importance of establishing instructors’ teaching presence and social presence as described in the community of inquiry (CoI) framework.

The CoI framework is composed of three interconnected and interdependent presences: the social, cognitive, and teaching presences (Arbaugh et al., 2008; Choo et al., 2020; Shea & Bidjerano, 2010). Social presence refers to how members of a learning community are able to “project their personal characteristics into the community” (Garrison, 2011, p. 5, as cited in Lower, 2022, p. 511). Components of social presence include students’ sense of belonging, participation in a trusting environment, and personal and affective relationships (Choo et al., 2020; Lower, 2022). Online courses can present challenges for social presence due to isolation from the instructor and other students, and a lack of meaningful social interaction (Choo et al., 2020; Tavares, 2024). An online community that fosters a sense of belonging among students helps decrease social isolation (Choo et al., 2020). Cognitive presence is seen in the ability of CoI participants to co-construct knowledge and meaning through ongoing engagement with one another (Garrison et al. 2001). This presence is closely related to the process and outcomes of critical thinking (Garrison et al. 2001; Lower, 2022). In this study, we readily acknowledge we are merely making connections to these principles in the course design and uptake, not formally measuring them with tested CoI measurement tools (Arbaugh et al., 2008).

Similar to UDL and Lowenthal et al.’s (2020) inclusive teaching principles, teaching presence is the design and facilitation of learning that is both personally and academically relevant to students (Anderson et al., 2001). Components of teaching presence include setting the curriculum, establishing group norms, and facilitating productive discourse to sustain learner engagement by encouraging and acknowledging student contributions (Shea et al., 2006). In their study, Shea et al. (2006) demonstrate that students are more likely to report higher levels of learning and a sense of community when they perceive a salient teaching presence on the part of their instructors. Teaching presence is often shared among instructor, teaching assistants (TA), and students. The instructor and TA design the course modules, assignments, and activities, to provide learning experiences that enhance the cognitive and social presence of students (Choo et al., 2020; Lower, 2022). It is also essential for students to assume teaching presence to increase self-directed learning and self-efficacy (Lower, 2022). In this way, teaching presence is connected to and can support learning presence, which is composed of the motivational, metacognitive, and behavioural traits and characteristics of online learners (Shea & Bidjerano, 2010). Learners’ self-efficacy and self-regulation are central to learning presence. In other words, learners’ mental states and perception of their ability to improve despite failures, accomplish tasks and achieve desired outcomes in a course affects the learning presence (Shea & Bidjerano, 2010). If the learner feels motivated to improve despite challenges and failures, this can lead to higher levels of cognitive presence. Effective teaching presence and social presence can improve self-efficacy of learners and positively impact learning presence; this is particularly relevant in the context of a remotely delivered course for first year international students.

Annotation is the process of adding notes to texts, enabling people to comment on and engage with texts and other readers (Kalir & Garcia, 2021; Morales et al., 2022). Digital annotation tools in education can help students to annotate online texts and engage in dialogue with peers (Morales et al., 2022). One type of learning technology is social annotation which provides an online social platform for students to annotate digital texts and resources, share information and ideas, and co-construct knowledge (Clinton-Lisell, 2023; Kalir et al., 2020).

Research shows that social annotation technology improves students’ critical thinking, reading comprehension, and cognitive skills and enhances student motivation, collaboration, peer review, and community building in undergraduate and graduate classes (Kalir et al., 2020; Morales et al., 2022). Furthermore, Clinton-Lisell (2023) found that social annotation facilitated students’ self-expression in their ability to relate personally to the text. In the context of the internationalisation of higher education, students come from a variety of backgrounds, including students who have been historically underserved by traditional educational systems (Clinton-Lisell, 2023). Social annotation is an opportunity for representational justice, as these historically-underrepresented students are able to insert themselves into the text. This increases students’ sense of belonging by weaving in their voices as they interact with a text, and is more effective than individual notetaking (Clinton-Lisell, 2023). This collaborative dialogue attempts to compensate for face-to-face opportunities international students value as they “employ language in creative and dynamic ways to respond to their peers’ comments and questions” (Tavares, 2024, p. 218). Social annotation can be conceptualised as multilayered writing where students engage with and build upon one another’s comments and queries to build community, co-construct knowledge, and strengthen engagement in the learning. Annotation threads become “a generative space to theorize, enhance, complicate, and question our thinking as [we] navigate the claims [we] make” (Sterner & Fisher, 2020, p. 68). We feel attending to language features through collaborative discussion threads are steps toward abstracted reflection and metacognition, an important part of developing critical language awareness.

Another aspect of social annotation is peer review. Students engage with each other’s comments and queries, helping one another by offering corrections, revisions, and recommendations for further resources. Peer review helps to improve student learning and enhance mutual investment in the learning community through both teaching and learning presences (Shea & Bidjerano, 2020). Research shows that students who provide feedback to other students help to improve their own work (Cho & Cho, 2011; Li et al., 2010). There is a significant relationship between the quality of feedback that students provide and the quality of their own work (Guasch et al., 2013; Li et al., 2010).

This case study of academic literacy instruction employed inclusive pedagogical design principles and social annotation in two sections of student work from an online course conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a case study, its scope is naturally limited, but it allows us to focus on authentic examples of teaching and learning during the widespread shift to remote teaching. As such, it demonstrates “engagement with the complexities of classrooms, schools and other learning contexts” (Hamilton, 2024, p. 195). Its complexities include the range of emergent academic literacies that are typical of first-year students and are amplified by their diverse academic backgrounds and the remote nature of pandemic study. The differing time zones, varying Internet bandwidth, and the lack of a contained classroom environment necessitated an accessible means of engagement that would suit a tailored pedagogic approach best (Tavares, 2024), and is representative of customized pedagogic and research support provided by some universities’ teaching and learning centres (Sharif et al., 2024). This case study focuses on students’ engagement with both the course content and one another through their writing, analysing a collection of annotations in the margins of assigned texts and a personal reflection on learning.

Deployed in the 2020–2021 academic year, a revised 26-week course spanned two semesters and was offered to students concomitantly enrolled in human geography, history, and psychology courses for their first year of remote study in Canada. The authors served as the instructor and teaching assistant for both sections of the course offering with 21 and 25 students, respectively.

A concerted effort to make the course design streamlined and explicit to students was made, as “creating a high-quality online learning experience begins and ends with the design of the course” (Lowenthal et al., 2020, p. 12). The course began with two weeks of introductory activities which aimed to establish the purpose, structure, and expected standards of the course, as well as the means of engagement for individual and group activities. Students were assigned to a group to choose a disciplinary text from their concomitant courses to annotate over the course of the unit. The course closed with individual student reflections on their learning. The scope and sequence of the units and activities are outlined in Table 1.

Using the language feature or academic literacy device covered in that week’s lesson, students were asked to find and/or query examples within their chosen group text. They were also asked to support their group’s learning through comments, questions, responses, and additional explanations. Annotations were graded individually. As a pedagogic activity, annotating was intended to focus students’ attention on the language features used by the author(s) in writing the text, thereby aiding their comprehension and encouraging them to deploy these features in their own writing. In line with accessibility and student needs, Sareen and Mandal advocate for incorporating a behaviourist-constructivist pedagogical approach for online and blended courses, combining elements of behaviourist and constructivist frameworks. Behaviourist refers to instructivist or traditional approaches that focus on instructor lectures, knowledge transmission, and clearly defined course objectives, whereas constructivist frameworks for learning are situated in organic, collaborative, emergent, and developmental planning (2025, p. 3). In the absence of behaviourist pedagogies, where much control is left to the students to co-construct and facilitate their own learning, there is the challenge of assumed learning, which may not lead to effective teaching and learning (Sareen & Mandal, 2025). When designing this course, the authors implemented a behaviourist-constructivist framework (Sareen & Mandal, 2025), emphasizing the need for both lecture-based content, knowledge transmission, and collaborative knowledge construction through student group work and discussions.

Table 1

Scope and Sequence of the Course

| Unit 1: Clause constituents | Unit 2: Texture of texts | Unit 3: Evaluation | Unit 4: Argumentation | Final task: Course reflection | |

| Lecture and practice activities | Individual and group activities (practice quizzes, discussion boards, uploads of additional examples from disciplinary texts, etc.). | Individual reflection on learning about language feature, academic literacy, or working in a group. | |||

| Text choice | Process and rationale for the selection of the text to annotate for the unit. Written and assessed as a group. | ||||

| Annotations | Individually written and assessed within shared group text in CLAS. | ||||

| Feature analysis | Synthesis of the unit’s annotations within the shared group text connecting language features to meaning making of the text. Written and assessed as a group. | ||||

| Peer evaluation | Individual scores and feedback to group members’ contributions to group learning through annotations and group writes. | ||||

Note. Collaborative Learning Annotation Software (CLAS).

Teaching presence (Shea et al., 2006) was developed through active engagement between the instructor and TA with students, e.g., through purposeful and supportive messaging. This set the course norm of a welcoming and supportive space, which can be important to international students who are studying remotely and building an online community (Tavares, 2024). Lectures referred to foundational concepts that had been previously introduced, encouraging students to revisit these archived resources as needed. Teaching presence was also established through instructor and TA explanations and feedback. Challenges and triumphs were acknowledged in lectures, instructions, assignment feedback, and announcements. Designing meaningful and sustained communicative and collaborative activities for online courses was part of the teaching presence. For example, the course’s introductory activity was a still life selfie, in which each student shared a photo of artefacts representing themselves and explained their choices. This gave everyone the opportunity to curate their presentation to the cohort without revealing too much about themselves too soon.

Community building continued in the form of sustained group work, during which students provided and engaged with peer feedback, and reflected on their group work. In these instances of shared teaching presence, students took on the responsibility of teaching and learning from one another, in addition to incorporating instructor and TA feedback. The instructor and TA served as the bridge between students and the professional and academic community, modeling scholarly engagement and providing opportunities for students to teach each other. This knowledge exchange between instructors and students demonstrated that knowledge is co-constructed (Lower, 2022). At the end of each unit, student groups synthesized what they had learned about disciplinary meaning-making within their shared text and annotations through a jointly constructed essay. They graded one another’s contributions to the group’s learning through an online peer assessment tool. The innovative peer review took place at the point of engagement and inquiry, during the social annotations and through the process of reading. It was embedded throughout the process as students navigated the texts and constructed meaning. In contrast, a more typical peer review involves checking a draft assignment once most of the thinking, organising, and writing has been completed. Also, typical peer review often serves as a function for grade improvement (“Can you check this to ensure I haven’t made mistakes/help me get a better mark?”) rather than genuine inquiry for comprehension.

Each unit was similarly organised, giving students the opportunity to improve their proficiency and performance as the course progressed. The consistent module design, chunking of course content, and referring to connections between previous and new material align with Lowenthal et al.’s (2020) principles of accessible and inclusive pedagogy and course design. Students engaged in a series of group and individual learning tasks, organised into four units over the 26 weeks. The focus of each unit aligned with the three interacting metafunctions of language, as informed by functional grammar. This approach moved from the smaller pieces of language to how they interact to shape texts, and then to how texts, authors, and audiences interact with each other to shape and be shaped by context.

The pedagogic use of social annotation aligns with Morales et al.’s (2022) purpose of enabling knowledge construction, shared meaning-making, and collaborative learning. Social annotation also serves as a means of collecting data for this study, providing a stable representation of students’ engagement with their texts (and therefore their emerging academic literacies), as well as their engagement with one another. Common social annotation platforms include Hypothesis.is and Perusall.com. For this pedagogic project and study, the Collaborative Learning Annotation Software (CLAS) platform, which was developed by our university and adhered to the province’s Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act, was used. This meant that all data were stored on Canadian Internet servers, which was important for protecting students’ data privacy, particularly when they were engaging in potentially politically sensitive topics in their history, human geography, and psychology courses. Further, this approach aligned with the university’s statement on protecting students, which acknowledged that some course content (i.e., geopolitics, human rights, sexual orientation, etc.) might be considered controversial or even banned in some countries.

To utilize the social annotation platform, student groups uploaded their chosen text into a group assignment created in the CLAS settings. Once uploaded to the group folder, students could access and annotate the text asynchronously over each multi-week unit. The shared platform embedded with the course’s learning management system aligned with Lowenthal et al.’s first principle of “accessible and usable course and content” (2020, p. 8).

Ethics approval from the institution to collect and analyse student work was obtained before the course began. A university colleague who was not involved in the course managed which students opted in or opted out of having their data included. This information was shared with the instructor upon completion of the course and submission of final grades, to ensure that the instruction and interaction between instructors and students did not differ based on whether students opted in or out of the study. Additionally, any identifying characteristics within student annotations were deleted.

Over the 26-weeks, the 46 students generated more than 3,000 annotations (or responses to peers’ annotations) across their four units of study. Groups of four to five students averaged 78.5 annotations per shared text, with the lowest number of annotations (22) on the first unit and the highest number of annotations (144) on the fourth and final unit. Groups consistently wrote more in the margins of their shared texts as the course progressed, suggesting cumulative knowledge building, as they were encouraged to revisit and annotate features of earlier lesson foci as useful, and confidence in engaging with one another.

Table 2

Annotation Assessment Criteria

| Criteria | Assessment |

| Quantity of comments | Did students annotate enough? |

| Tagging | Did students tag annotations correctly and from the various lessons in the unit? |

| Accuracy | Did students’ annotations match the text excerpts they had chosen? Did students ask/give the correct details? |

| Relevance | Did students’ annotations focus on important information and/or excerpts? |

| Collaborative discussion | Did students engage their group members through annotation? |

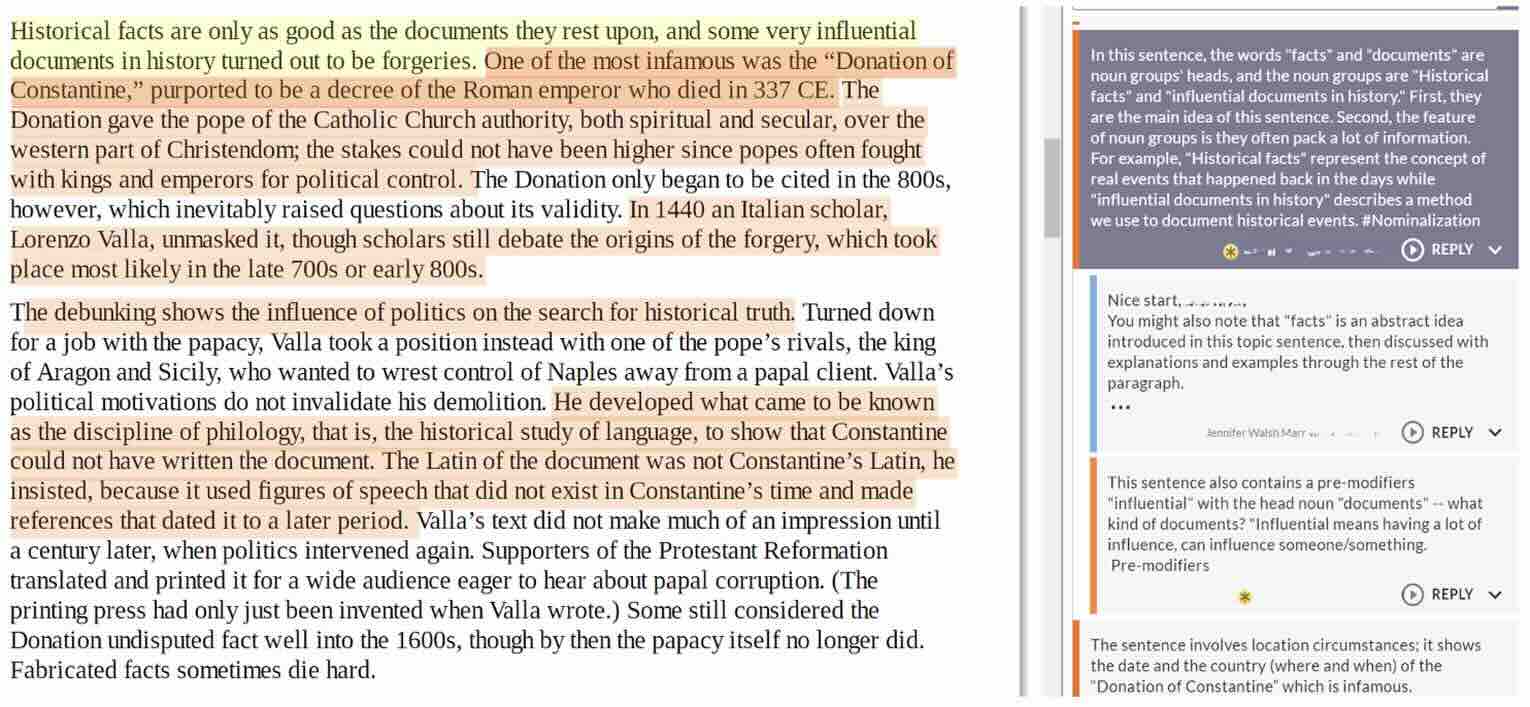

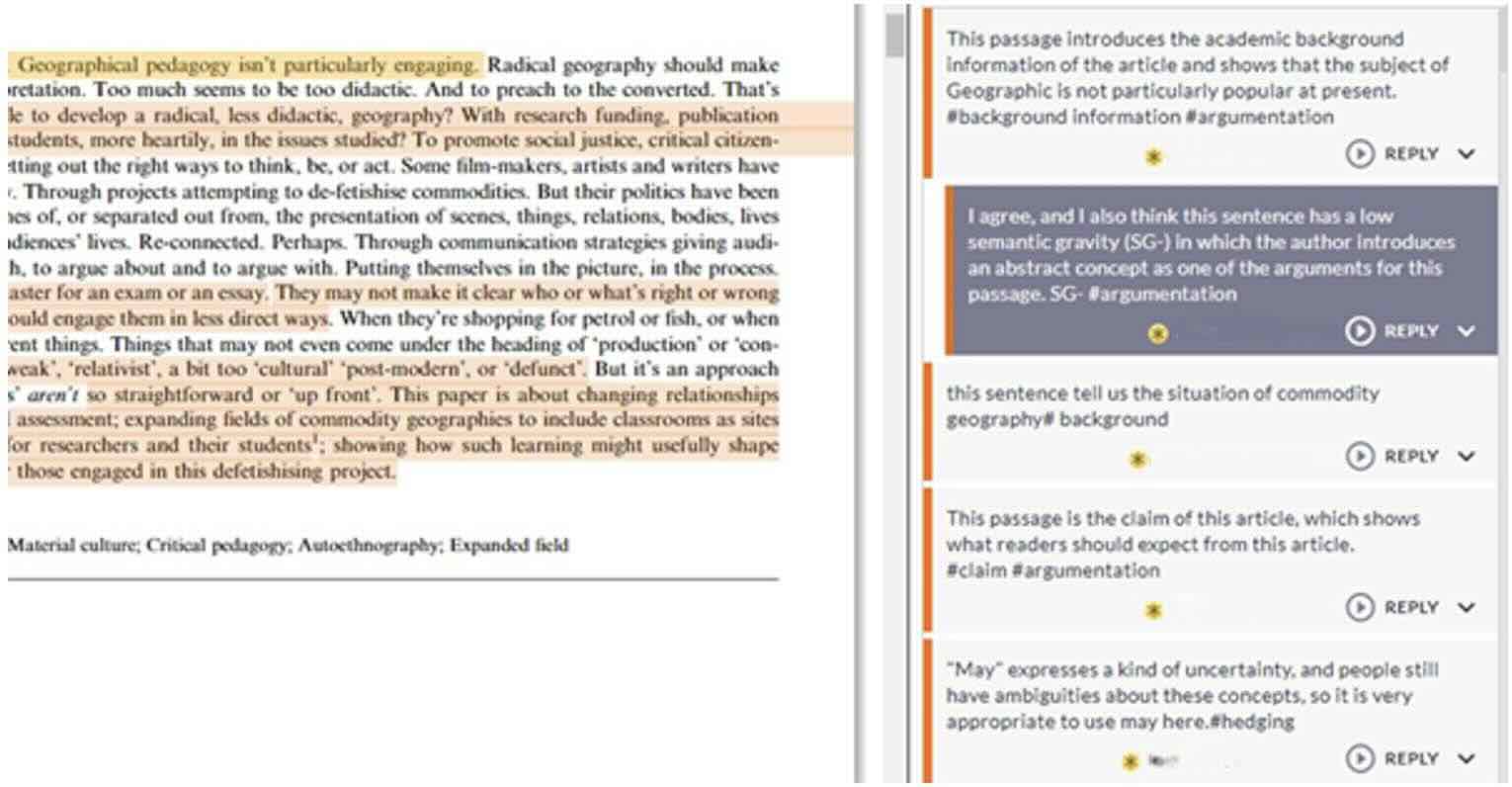

The example annotation in Figure 1 shows a student-initiated thread engaging with the focus of a unit on the building blocks of academic language. It highlights the main ideas of the excerpt manifest in the head nouns “facts” and “documents” within the paragraph’s topic sentence. Subsequent comments, by both the instructor and classmates, discuss the noun groups’ roles and premodifiers, contributing to enhanced academic literacy.

Figure 1

Students’ Social Annotations on Collaborative Learning Annotation Software

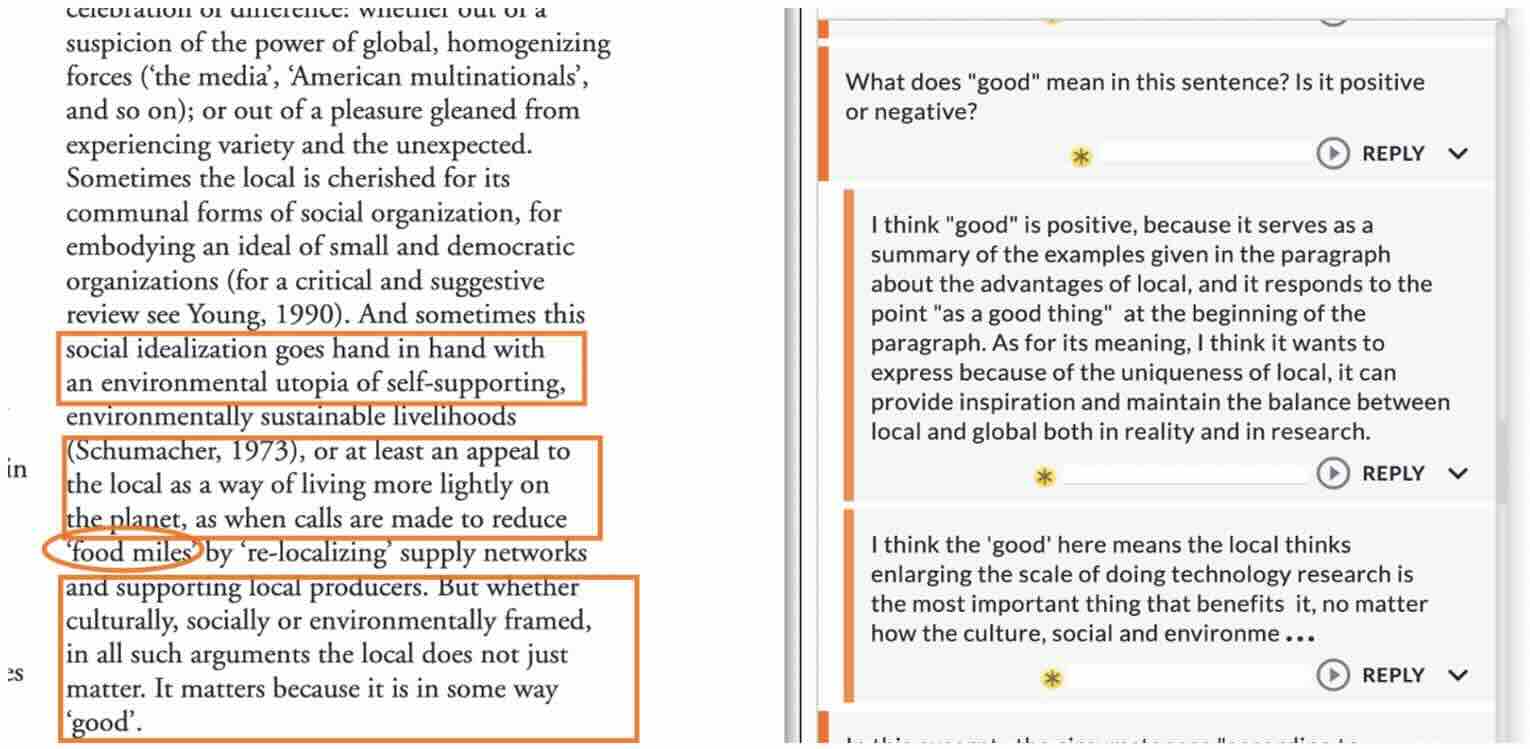

Figure 2 is an example of the students critically engaging with the connotation of the word “good” (in quotation marks in the original) in the closing sentence. The first student asks if its meaning is positive or negative and two students follow up with their response and rationale.

Figure 2

A Snippet of Students’ Social Annotations and Interaction

In Figure 3, one student builds upon a classmate’s annotation and expands its relevance beyond the original scope. They acknowledge the unit’s focus on argumentation and revisit previous lessons on semantic gravity, representing cumulative learning and connections across units.

Figure 3

Snippet of Expanded Discussion

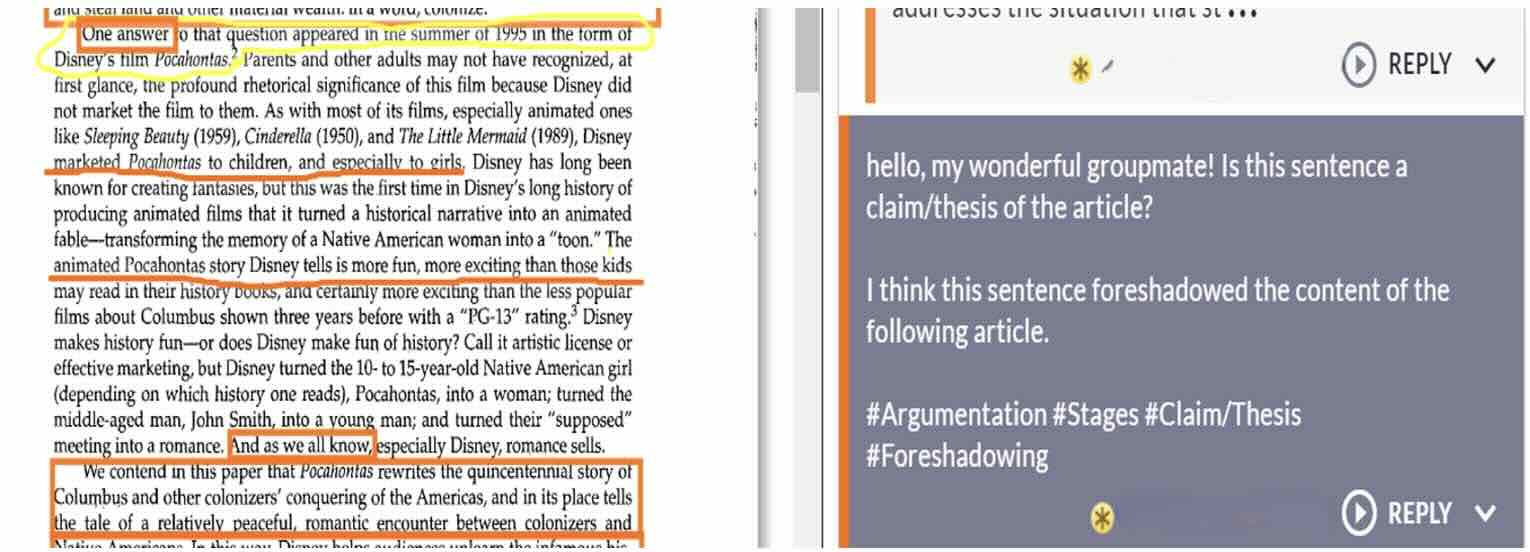

The Figure 4 snippet of a partial thread begins with an unequivocally friendly salutation and shifts to Student 1’s query regarding the article’s claim/thesis. Support is offered, then some hashtags to reiterate the major themes of the post (satisfying the tagging criterion). The first response continues to foster engagement by addressing the initial poster by name, giving their opinion, then returning to sociality by stating, “I’m not sure. What do you think?” The initial poster responds with more social gestures (greeting Student 2 by name, reduced, friendly forms of language) with some teaching content inserted between the friendliness. Two more students join the discussion, picking up the first two students’ teaching content, albeit without the same friendliness. The annotations are directly related to the course content and satisfy the rubric’s criteria for relevance, accuracy, and collaborative discussion.

S1: Hello, my wonderful groupmate! Is this sentence a claim/thesis of the article?

I think this sentence foreshadowed the content of the following article.

#Argumentation #Stages #Claim/Thesis #Foreshadowing

S2: Hi [Student 1], I think this is still a part of the introduction where the author is providing the context of the claim. I’m not sure. What do you think?

S1: Hi [Student 2], ya ∼ I agree with u this is still a part of the introduction. But in somehow, i feel like it has foreshadowed the rest of the content of the following article, and i think it is also what does the author want the reader to accept... im not sure either. that’s why it is good to be discuss and thank u for ur idea!!!!

S3: Yea. I also agree it is still the introduction. The reason is that it continues to develop the content from the beginning, and you can see the main theme here does not change. Even though it looks so long, and it is still part of the introduction. The most important thing is about content, and how content develops.

S4: In my opinion, it is probably too short to be the thesis for this article. Moreover, it doesn’t have the major points and claims that are showing the article’s significance.

Figure 4

A Student’s Friendly Annotation

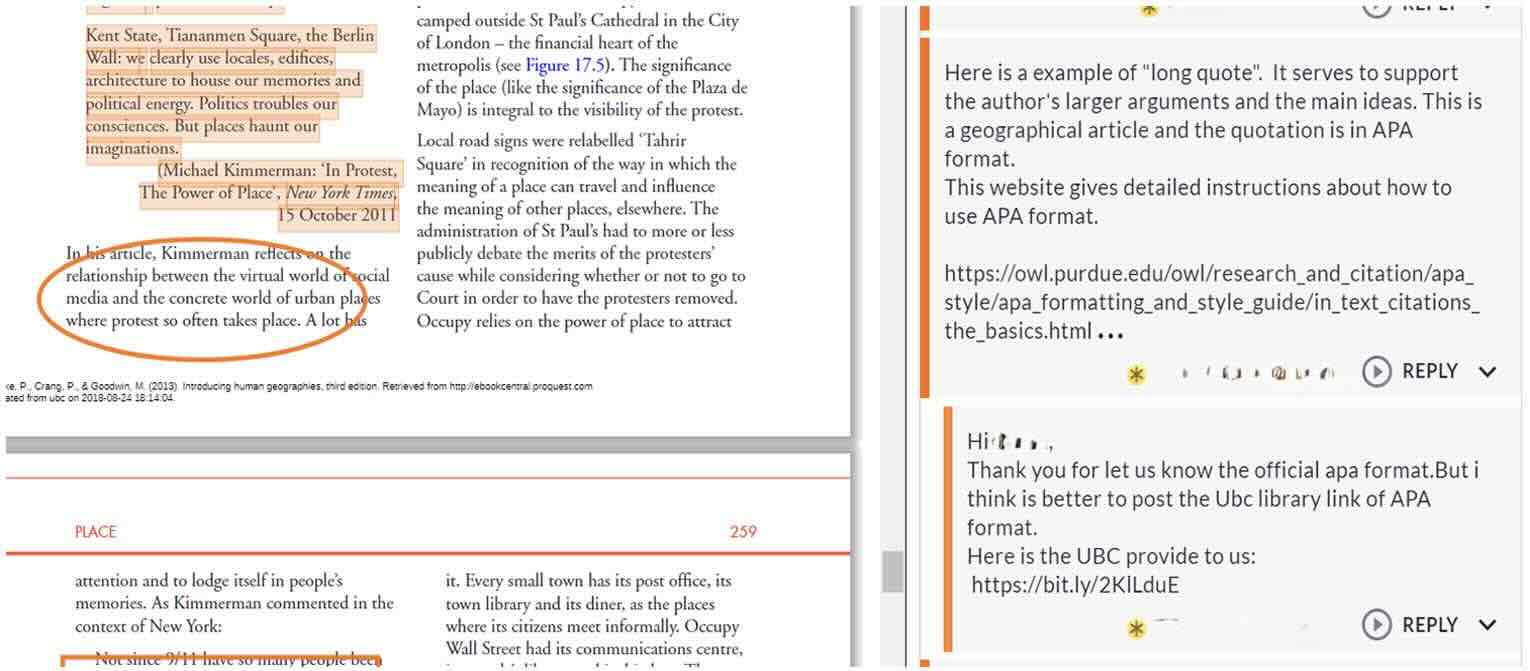

The Figure 5 snippet also includes some niceties toward the peer group (“Thank you for let[ting] us know...”) as well as co-constructing knowledge, as the two students supply the group with external resources to support their APA citation practices. The first student identifies the excerpt as a long quote and highlights its purpose in supporting the author’s ideas, then provides a hyperlink to the Purdue University online writing lab (OWL) instructions. The second student acknowledges this but suggests using the web-based resources developed in house by the university library. In the excerpted student assignment, a group describes their concern about establishing consensus, their process for collecting input, and their satisfaction with the result:

“...after our further discussion, we made a full agreement on choosing this article. We all believe that the analysis of this text, as mentioned above, is also of great value to us. Before we wrote this paragraph, we were concerned about how we could sum up our diverse ideas. So we decided to write everyone's ideas under each question, just like last time, and then summarize them. Before we submitted this assignment, this paragraph was also sent to our group chat, and it was submitted after each of us agreed. During the process, everyone was free to express his or her own opinions and modify the paragraph with the permission of others.... They support the purposes that we want to learn from each other, enrich our understanding, and develop the use of language through group cooperation. The process of cooperation is very enjoyable. It allows each of us to express our own ideas freely and understand the different perspectives of others. Like this paragraph, it is made up of everyone's cooperation, and we believe that our friendly cooperation and the way we cooperate respectfully express the ideas of each participant.”

Figure 5

Students Sharing Resources in Their Social Annotation

In keeping with UDL principles of meaningful options to engage with course content, the final course task was an individual reflection assignment (CAST, 2018; Lowenthal et al., 2020). Students were prompted to do the following:

Think about the group work you completed through the course and what worked well, was a challenge and/or you learned. What have been some of the various factors of your success, challenges & learning, and how might you apply these lessons to your future studies and career? Write 2-3 paragraphs.

The excerpt from a student focuses on the challenges and successes of group work, embodying the engagement and community students were able to foster over the year:

“Working with others has never been easy for me... Throughout spending two terms with my group members in this course, I have learned something that might help me continue the efficient learning and socializing...First, I learned that knowing how to communicate is necessary to succeed in this course. From choosing the texts to writing their analysis, other group members and I always needed conversations to arrange each other’s annotation plan. For instance, some of the assignments got excellent grades when we had thoughtful discussions, and others are relatively lower because we did not properly discuss the topic. Although I did my part pretty well on the assigned group writing in Unit 1, other members and I didn’t get the grade we expected. [Our instructor] pointed out that we need to connect and build relationships in each part of the writing. After that, others and I soon realized the problem and corrected it on time to get a better grade next time.”

This student discussed how they had learnt the importance of communication and building relationships through group work. It is through dialogue and relationship-building in group work that a sense of belonging to an academic institution is fostered, leading to efficient learning, excellent grades, and academic success (Lower, 2022).

Social annotation is seen as both means and evidence of students’ academic literacy development and community building. Students were able to access teaching and learning resources within and beyond the course. Further, reflections highlight learning and teaching presence, and speak to the role of CoI in students’ sense of inclusion and belonging.

The examples in the Results section represent the categories of relevance and collaborative discussion, highlighting how students engaged with their disciplinary texts, the language within, and one another, “construct[ing] meaning through sustained communication” (Garrison et al., 2001, p. 89). The relevance of annotations is particularly tied to academic literacies, as the students highlight features of texts’ language, organisation, and connections between ideas within the context of disciplinary meaning-making. The examples demonstrate how students situate their emerging knowledge in relation to the course content by tagging lecture concepts and showing thought processes within the task structure.

The snippet and subsequent transcript of the annotation thread in Figure 4 represents students’ relationship and rapport with one another, indicating a burgeoning community and mutual investment in one another’s understanding of the course content.

The final snippet in Figure 5, represents learning presence (Shea & Bidjerano, 2010) explicitly through individual students’ contextualized engagement with the course content and peers in the margin of course readings. Through purposeful task design, direct instruction and feedback, teaching presence “articulate[d] the specific behaviours likely to result in a productive community of inquiry” (Shea & Bidjerano, 2010, p. 1722). That community was fostered through the group tasks and instructional support that were present throughout each unit. This began with the selection of a disciplinary text, which group members had to annotate, before explaining the process and rationale in a group text.

The iterative process to seek peer input to improve understanding of a text indicates positive emotions related to learning and group work, and an investment in the group as a whole. It also points to social presence within a community of inquiry which “promotes positive affect, interaction and cohesion... that support a functional collaborative environment” (Shea & Bidjerano, 2010, p. 1722). Within its consistent modular design, the course incorporated both individual behaviourist learning opportunities (lectures, quizzes) and constructivist learning tasks (shared annotations, group texts, peer review) (Sareen & Mandal, 2025).

The group write on consensus-building suggests significant co-regulation (Shea & Bidjerano, 2010) and metacognition within the group. The final individual reflection on learning throughout the course also served to support students’ metacognition (Butler et al., 2017), encouraging them to reflect on their own thought processes and learning. It was an individual writing task for which explicit instruction had been provided on the often implicit expectations of reflective writing (Martin & Walsh Marr, 2024; O’Sullivan, 2017). The task also helped students recognize and celebrate all they had accomplished during such an unusual academic year.

This case study was an impromptu response to remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic and not set up with formal measurement tools to empirically measure and validate teaching, social, and cognitive presences of communities of inquiry (Arbaugh et al., 2008). As such, social annotation was the most appropriate tool for engaging first-year students around the world with academic literacies and for delivering accessible, relevant content in context. Future course designers are encouraged to use these tools to enhance their instructional design.

This innovative instructional design promoted inclusion and accessibility for first-year students through encouraging social annotation and raising awareness of critical language. Attention to academic disciplinary practices helped to facilitate the transition of linguistically and culturally diverse students to a Canadian university by building their academic literacies. Learning about linguistic features within academic texts enabled a wider and more critical scope of student participation and success. Through collaborative annotation and writing, students supported one another’s learning and deepened their own learning. They gained insight into what disciplinary texts said and how those ideas were articulated in the texts. Bespoke teaching materials were based on texts and assignments of students’ concomitant disciplinary coursework, highlighting how meaning is constructed and valued in these fields and supporting novice scholars’ participation. The curriculum revisited and built upon foundational concepts over two semesters, deepening students’ familiarity with, and ability to engage with, increasingly sophisticated disciplinary meaning-making.

Despite course participants being at a significant distance from one another through an international pandemic, learning communities were fostered through social annotation and group tasks. Teaching presence was manifest in a clear curricular structure, consistent assessment criteria, and sustained engagement through student learning cycles, including formative feedback. The consistent structure and clarity of expectations created an accessible and inclusive student learning environment (Lowenthal et al., 2020). The use of social annotation over several weeks scaffolded more careful, reflective engagement, due to ongoing interaction within groups. These groups established a strong rapport over the two semesters. Their authentic academic and social engagement with challenging texts and circumstances indicated resilience and self-regulation. Furthermore, social annotation provided critical engagement with texts and knowledge, as well as community building with peers. This shift towards accessible and inclusive pedagogy should benefit learners in any context.

Anderson, T., Rourke, L., Garrison, R., & Archer, W. (2001). Assessing teaching presence in a computer conferencing context. Online Learning, 5(2). https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v5i2.1875

Arbaugh, J. B., Cleveland-Innes, M., Diaz, S. R., Garrison, D. R., Ice, P., Richardson, J. C., & Swan, K. P. (2008). Developing a community of inquiry instrument: Testing a measure of the community of inquiry framework using a multi-institutional sample. The Internet and Higher Education, 11(3), 133-136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2008.06.003

Basset, M., & Macnaught, L. (2024). Embedded approaches to academic literacy development: A systematic review of empirical research about impact. Teaching in Higher Education, 30(5), 1065-1083. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2024.2354280

Beers, M. A., Hall, M. L., Matthews, A. G. W., Elmore, D. E., Oakes, E. S. C., Goss, J. W., & Radhakrishnan, M. L. (2021). A fully integrated undergraduate introductory biology and chemistry course with a community‐based focus I: Vision, design, implementation, and development. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education, 49(6), 859-869. https://doi.org/10.1002/bmb.21565

Bond, B., (2020). Making language visible in the university: English for academic purposes and internationalization. Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781788929301

Butler, D., Schnellert, L., & Perry, N. E. (2017). Developing self-regulated learners. Pearson.

Centre for Applied Special Technology. (2018). Universal design for learning guidelines. Version 2.2. https://udlguidelines.cast.org/

Cho, Y. H., & Cho, K. (2011). Peer reviewers learn from giving comments. Instructional Science, 39(5), 629-643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-010-9146-1

Choo, J., Bakir, N., Scagnoli, N. I., Ju, B., & Tong, X. (2020). Using the community of inquiry framework to understand students’ learning experience in online undergraduate business courses. TechTrends, 64(1), 172-181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-019-00444-9

Clinton-Lisell V. (2023). Social annotation: what are students’ perceptions and how does social annotation relate to grades?. Research in Learning Technology, 31. https://doi.org/10.25304/rlt.v31.3050

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2001). Critical thinking, cognitive presence, and computer conferencing in distance education. American Journal of Distance Education, 15(1), 7-23. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923640109527071

Guasch, T., Espasa, A., Alvarez, I. M., & Kirschner, P. A. (2013). Effects of feedback on collaborative writing in an online learning environment. Distance Education, 34(3), 324-338. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2013.835772

Hamilton, L. (2024). Case study research in education: Considering possible paradoxes and concerns. In P. Rule & V. M. John (Eds.), Handbook of case study research in the social sciences (pp. 194-214). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781803920320.00022

Kalantzis, M., Cope, B., Chan, E., & Dalley-Trim, L. (2016). Literacies (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Kalir, J. H., Morales, E., Fleerackers, A., & Alperin, J. P. (2020), “When I saw my peers annotating”: Student perceptions of social annotation for learning in multiple courses. Information and Learning Sciences, 121(3/4), 207-230. https://doi.org/10.1108/ILS-12-2019-0128

Kalir, R., & Garcia, A. (2021). Annotation (1st ed.). The MIT Press.

Klinger, C., & Murray, N. (2012). Tensions in higher education: Widening participation, student diversity and the challenge of academic language/literacy. Widening Participation and Lifelong Learning, 14(1), 27-44. https://doi.org/10.5456/WPLL.14.1.27

Lea, M. R., & Street, B. V. (1998). Student writing in higher education: An academic literacies approach. Studies in Higher Education, 23(2), 157-172. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079812331380364

Li, L., Liu, X., & Steckelberg, A. L. (2010). Assessor or assessee: How student learning improves by giving and receiving peer feedback. British Journal of Educational Technology, 41, 525-536. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2009.00968.x

Lillis, T. (2006). Moving towards an ‘Academic Literacies’ pedagogy: Dialogues of participation. In L. Ganobcsik-Williams (Ed.), Teaching academic writing in UK higher education: Theories, practices and models (pp. 30-46). Bloomsbury. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-230-20858-2

Lowenthal, P. R., Humphrey, M., Conley, Q., Dunlap, J. C., Greear, K., Lowenthal, A., & Giacumo, L. A. (2020). Creating accessible and inclusive online learning: Moving beyond compliance and broadening the discussion. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 21(2), 1-21.

Lower, M. L. P. (2022). Communities of inquiry pedagogy in undergraduate courses. Law Teacher, 56(4), 507-521. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069400.2022.2075109

Maldoni, A. M. (2018). “Degrees of deception” to degrees of proficiency: Embedding academic literacies into the disciplines. Journal of Academic Language and Learning, 12(2), 102-129. https://journal.aall.org.au/index.php/jall/article/view/408

Martin, J. L., & Walsh Marr, J. (2024). Framing the looking glass: Reflecting constellations of listening for inclusion. In N. Tilakaratna & E. Szenes (Eds.), Demystifying critical reflection: Improving pedagogy and practice with legitimation code theory. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003177210-13

Morales, E., Kalir, J. H., Fleerackers, A., & Alperin, J. P. (2022). Using social annotation to construct knowledge with others: A case study across undergraduate courses [version 2; peer review: 2 approved]. F1000Research, 11, 235. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.109525.2

Nallaya, S., Hobson, J. E., & Ulpen, T. (2022). An investigation of first year university students’ confidence in using academic literacies. Issues in Educational Research, 3(1), 264-291. http://www.iier.org.au/iier32/nallaya.pdf

Nye, A. (2015). Building an online academic learning community among undergraduate students. Distance Education, 36(1), 115-128. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2015.1019969

O’Sullivan, D. (2017, March 5). Reflective writing [Video File]. Monash College. https://vimeo.com/207029935.

Sareen, S., & Mandal, S. (2024). Behaviourist-Constructivist Pedagogical Design Possibilities Within the Community of Inquiry Framework. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 50(2), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.21432/cjlt28673

Sharif, A., Chan, J. C. K., Welsh, A., Myers, J., Engle, W., & Wilson, B. (2024). Leaving no students behind: Reimagining our design practices to remove barriers. In B. Wuetherick, A. Germain-Rutherford, D. Graham, N. Baker, D. J. Hornsby, & N. K. Turner, (Eds.). Online learning, open education, and equity in a post-pandemic world (pp. 191-209). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-69449-3_9

Shea, P., & Bidjerano, T. (2010). Learning presence: Towards a theory of self-efficacy, self-regulation, and the development of a [ sic ] communities of inquiry in online and blended learning environments. Computers & Education, 55(4), 1721-1731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.07.017

Shea, P., Li, C. S., & Pickett, A. (2006). A study of teaching presence and student sense of learning community in fully online and web-enhanced college courses. The Internet and Higher Education, 9(3), 175-190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2006.06.005

Smith, J. C., Nichols, S. R., Yoo, S., & Oehler, K. (2009). Building a community of inquiry in a problem-based undergraduate number theory course: The role of the instructor. In D. A. Stylianou, M. L. Blanton & J. Knuth (Eds.), Teaching and learning proof across the grades (pp. 307-322). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203882009-18

Sterner, S. K., & Fisher, L. C. (2020). Expanding academic writing: A multilayered exploration of what it means to belong. Taboo, 19(5), 65-80. https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/taboo/vol19/iss5/5

Tavares, V. (2024). Online instruction and international students: More challenges for a vulnerable population. In B. Wuetherick, A. Germain-Rutherford, D. Graham, N. Baker, D. J. Hornsby, & N. K. Turner (Eds.), Online learning, open education, and equity in a post-pandemic world (pp. 211-230). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-69449-3_10

van Heerden, M., & Bharuthram, S. (2023). “It does not feel like I am a university student”: Considering the impact of online learning on students’ sense of belonging in a “post pandemic” academic literacy module. Perspectives in Education, 41(3), 95-106. https://doi.org/10.38140/pie.v41i3.6780

Walton, G. M., & Cohen, G. L. (2007). A question of belonging: Race, social fit, and achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(1), 82-96. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.82

Wingate, U., & Tribble, C. (2012). The best of both worlds? Towards an English for academic purposes/academic literacies writing pedagogy. Studies in Higher Education, 37(4), 481-495. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2010.525630

Zappa‐Hollman, S., & Fox, J. A. (2021). Engaging in linguistically responsive instruction: Insights from a first‐year university program for emergent multilingual learners. TESOL Quarterly, 55(4), 1081-1091. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.3075

Jennifer Walsh Marr is an English for Specific Academic Purposes instructor at Vantage College, University of British Columbia in Canada, and a PhD candidate at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education at the University of Toronto, Canada. Her praxis foci have included the portrayal of settler-Indigenous histories, genre-informed pedagogy, and linguistically responsive instruction. Her current research focuses on university instructors’ language ideologies and pedagogic practices. Email: jennifer.walshmarr@ubc.ca

Shihua Tan is a PhD student in Educational Studies at the University of British Columbia, Canada. Her research interests include environmental and sustainability education, teacher education, lifelong learning and adult education. She is a graduate teaching assistant who has worked with undergraduate international students and pre-service teachers. Email: dtan1907@gmail.com