Vanhitha Kernagaran, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia

Amelia Abdullah, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia

This study investigates the impact of process writing and flipped learning on enhancing students' extended essay writing performance and higher-order thinking skills (HOTS). The process writing approach emphasises writing as a recursive activity involving multiple drafts, feedback, and revisions to improve coherence and clarity. A quasi-experimental design was applied, involving 120 Form Four students in northern Malaysia. Participants were divided into an experimental group, which received process writing-based flipped learning instruction, and a control group, which received textbook-based instruction in a flipped setting. Data were collected through pre-test and post-test assessments of writing and HOTS, along with qualitative feedback from student interviews. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) revealed significant improvements in the experimental group's writing across content, communicative achievement, organisation, and language use. Additionally, the experimental group showed marked growth in HOTS, particularly in analysing, evaluating, and creating. Although originally proposed in 1981, Flower and Hayes' model remains relevant for understanding the cognitive processes involved in students during writing, especially in instructional design contexts. This study supports the integration of process writing and flipped learning to enhance writing performance and HOTS, offering practical insights for educators seeking an effective and engaging instructional approach in teaching and learning of extended essay writing.

Keywords: extended writing, flipped learning, higher-order thinking skills, process writing, writing performance

Cette étude examine l’impact du processus de rédaction et de la classe inversée sur l’amélioration de la rédaction de dissertations et des habiletés de pensée supérieures chez les élèves. Le processus de rédaction met l’accent sur l’écriture comme une activité récursive impliquant plusieurs brouillons, des rétroactions, et des révisions afin d’améliorer la cohérence et la clarté du texte. Une méthode quasi-expérimentale a été utilisée, impliquant 120 élèves de niveau scolaire Form four dans le nord de la Malaisie. Les personnes participantes ont été réparties en deux groupes : un groupe expérimental, qui a reçu un enseignement fondé sur le processus d’écriture utilisant une approche de classe inversée, et un groupe témoin, qui a reçu un enseignement basé sur un manuel scolaire également dans une approche de classe inversée. Les données ont été recueillies à l’aide d’évaluations prétest et post-test sur la rédaction et les habiletés de pensée supérieures, ainsi que par des entretiens qualitatifs avec les élèves. Une analyse de covariance (ANCOVA) a révélé des améliorations significatives chez les élèves du groupe expérimental dans les domaines du contenu, de la réussite communicative, de l’organisation et de l’usage de la langue. De plus, ce groupe a montré une amélioration notable des habiletés de pensée supérieure, particulièrement en matière d’analyse, d’évaluation et de créativité. Bien que proposé initialement en 1981, le modèle de Flower et Hayes reste pertinent pour comprendre les processus cognitifs liés à l’écriture des élèves, notamment dans le cadre de la conception pédagogique. Cette étude soutient l’intégration du processus de rédaction et de la classe inversée pour améliorer la performance en écriture et les habiletés de pensée supérieures, offrant des perspectives pratiques aux personnes enseignantes à la recherche d’approches pédagogiques efficaces et engageantes pour l’enseignement du processus de rédaction de dissertations.

Mots-clés : rédaction longue, classe inversée, habiletés de pensée supérieures, processus de rédaction, performance en écriture

There has been growing interest in exploring innovative strategies to improve writing performance and promote higher-order thinking skills (HOTS) among students. Among these, the process writing and flipped learning approaches have drawn particular attention due to their potential to enhance students' writing performance and promote HOTS abilities. The process writing approach, based on the collaborative work of Flower and Hayes (1981), emphasises the recursive nature of writing, where multiple drafts, peer feedback, and revision are integral components. On the other hand, flipped learning coined by Bishop and Verleger (2013), involves the pre-learning of content through resources before class, allowing for more active engagement and application during in-class activities. While both strategies have independently demonstrated success, little research has explored their combined effects.

Writing requires not just language skills, but critical thinking, decision-making, and the ability to revise ideas that complement each other, all of which align with the higher levels of Bloom's Taxonomy. The combination of flipped learning and process writing is thus pedagogically significant, as it allows students to improve their work through several steps of writing. The rationale behind combining process writing and flipped learning is their complementary nature, as they both offer student-centred and interactive learning, promoting students' independent exploration and application of writing concepts. By incorporating flipped learning, students have the opportunity to engage with writing concepts independently, allowing for a more in-depth understanding and application of these concepts during class time (Tucker, 2017).

The primary objectives of this research are twofold: first, to assess the effects of integrating the process writing approach and flipped learning on students' performance in writing extended essays; and second, to evaluate the development of the students' HOTS resulting from this instructional approach. These outcomes are vital in preparing students for 21st-century learning and lifelong problem-solving, particularly in an English as a second language (ESL) context where language development and cognitive growth must go hand-in-hand.

Process writing highlights the importance of writing as a multi-stage journey, prompting students to participate in prewriting, drafting, revising, and editing their work through several iterations prior to publishing (Seow, 2002). This approach significantly differs from the conventional product-oriented view of writing, which emphasises the outcome over the process involved in achieving it. The writing process is fundamentally viewed as a complex and recursive activity rather than a linear one, with substantial benefits derived from its division into manageable stages (Bayat, 2014).

Flower and Hayes (1981) provide a profound understanding of the cognitive processes involved in writing, as a cornerstone of the process writing approach. They indicate that writing is not limited to the mechanical act of composing words on paper, but it incorporates a sequence of cognitive activities, such as formulating ideas, drafting thoughts, and revising and editing content before publishing the essay. By concentrating on these stages individually, students can approach writing tasks with a greater sense of clarity and confidence, resulting in improved writing skills and outcomes (Allmendinger, 2017; Stefanou & Xanthaki, 2016).

The process writing approach creates a supportive classroom environment where students can explore ideas, focusing on expression rather than immediate perfection (Alodwan & Ibnian, 2014; Dörnyei & Muir, 2019; Faraj, 2015). Teachers act as facilitators, guiding students with feedback and encouragement throughout each stage, rather than as final judges of quality (Hayes & Flower, 2016). Incorporating the process writing approach in the classroom involves various activities that support each stage of the writing process (Bean & Melzer, 2021; Harris, 2023; Nabhan, 2019). Brainstorming sessions, peer reviews, and revision exercises are integral components helping students internalise the steps involved in producing a coherent and polished piece of writing. Such activities not only enhance students' writing skills but also promote a collaborative learning environment where ideas are shared and critiqued constructively.

Flipped learning in writing instruction represents a transformative approach to teaching and learning, effectively inverting the traditional classroom model to prioritise active learning and student engagement (Karabulut‐Ilgu et al., 2017). By delivering instructional content through online and offline mediums outside of the classroom, this innovative method allows for classroom time to be dedicated to more interactive, hands-on activities (Hava, 2021). Such activities may include discussions, collaborative problem-solving, and the practical application of genre-based elements in teaching and learning of writing. This model not only facilitates a deeper understanding of writing principles but also encourages students to apply these principles in a supportive, interactive environment.

The pioneering work of Bergmann and Sams (2023) and Lage et al. (2000) has been instrumental in demonstrating the efficacy of flipped learning in writing instruction (Amiryousefi, 2019). Their research highlights how this approach can lead to significant improvements in students' writing capabilities by fostering an environment that promotes active engagement and allows for personalised learning experiences. The flipped classroom model acknowledges the diverse learning needs and paces of students, providing opportunities for them to engage with instructional material at their own pace before coming to class (Campillo-Ferrer & Miralles-Martínez, 2021). This personalised engagement with the material prepares students to participate more fully in classroom activities.

In the context of writing instruction, the flipped learning model has potential to be integrated in the writing process which includes brainstorming, drafting, revising, and editing (Scott & Vitale, 2003). By engaging with instructional content prior to and outside of class, students are prepared to delve into more complex discussions and collaboration during in-class writing activities. This preparation and the in-class focus on application and feedback make the writing process more transparent and approachable for students, often demystifying aspects of writing that they may find challenging.

Moreover, flipped learning facilitates a shift from a teacher-centred classroom to a student-centred learning environment (Bond, 2020; Raman et al., 2021). This shift encourages students to take ownership of their learning, fostering a sense of responsibility and autonomy. In writing instruction, this autonomy is crucial, as it empowers students to explore their voices, experiment with different styles, and take constructive criticism in stride, viewing it as a necessary part of the writing process rather than a personal critique. The implementation of flipped learning in writing instruction also allows teachers to devote more in-class time to addressing individual and small group needs, thereby enhancing the feedback loop between student and teacher (Nerantzi, 2020; Raman et al., 2022). This personalised feedback is invaluable in writing instruction, where nuances, style, and structure can significantly impact the written work.

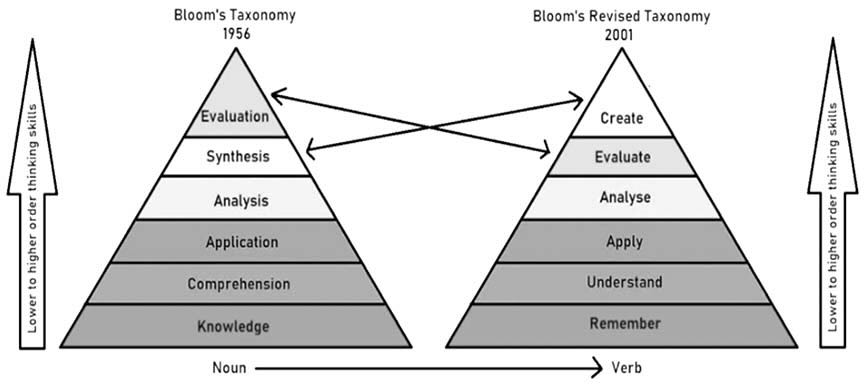

The incorporation of HOTS in writing instruction has been identified to significantly enrich the learning experience for students, promoting their involvement in complex cognitive processes such as analysing, evaluating, and creating rather than mere recall of information (Hyland, 2007). This paradigm shift is essential in cultivating critical thinking and advanced problem-solving abilities, which are essential for both academic and professional success. The revised version of Bloom's Taxonomy (Figure 1), as proposed by Anderson and Krathwohl in 2001, provides a comprehensive framework for the integration of these advanced cognitive skills into writing, offering a scaffolded approach to encourage deeper levels of engagement and to facilitate the production of more sophisticated outputs from students.

Figure 1

The Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy

>Note. Adapted from Anderson and Krathwohl (2001).

The emphasis on HOTS in writing instruction is grounded in the belief that writing is not just a mechanical skill but a complex intellectual activity that requires students to engage deeply with content, context, and audience (Yuliati & Lestari, 2018). By focusing on analysis, students learn to dissect texts, identify underlying themes, and understand different perspectives. Evaluation tasks push them to judge the validity of arguments, assess the quality of evidence, and synthesise information from multiple sources. Finally, creative tasks challenge students to generate original ideas, propose solutions, and articulate complex thoughts coherently. Incorporating these skills into writing instruction involves a variety of strategies and activities. The revised Bloom's Taxonomy offers educators a structured way to design these activities, ensuring that students are not only engaging with content at a surface level but are also challenged to apply, analyse, evaluate, and create based on what they learn (Quan et al., 2017). This approach fosters a deeper understanding of the subject matter and promotes cognitive skills that are essential for navigating complex academic and professional landscapes.

The synergistic integration of the process writing approach in the context of flipped learning offers a compelling and innovative framework for writing instruction (Lee, 2020). This fusion creates a dynamic, interactive learning environment that not only enhances students' writing skills but also significantly boosts their cognitive abilities. By leveraging the strengths of both approaches, educators can provide more personalised, process-oriented instruction in writing, while simultaneously fostering an atmosphere ripe for active learning and critical thinking in the classroom. These integrated approaches not only aim to elevate students' proficiency in writing but also seek to comprehensively develop their HOTS, thus offering a holistic approach to education addressing both skill acquisition and cognitive development (Bielinska, 2015; Deane et al., 2008; Schoonen et al., 2011). Rather than assuming guaranteed improvements, this study investigates whether this combined approach contributes meaningfully to students' writing performance and HOTS abilities.

The process writing approach emphasises writing as an iterative process cycle—prewriting, drafting, revising, editing, and publishing—rather than a one-off effort to produce a final product (Onozawa, 2010; Seow, 2002). This perspective encourages students to delve deeply into their writing, understanding it as a craft that requires patience, reflection, and continuous improvement. On the other hand, flipped learning flips the traditional educational model on its head by delivering instructional content outside the classroom, thus freeing up in-class time for interactive, hands-on activities that promote application, analysis, and synthesis of knowledge.

When these approaches are combined, students first engage with the conceptual and foundational aspects of writing outside the classroom, through digital platforms or pre-assigned readings. This preparation allows them to be ready when entering the classroom to actively participate in discussions, collaboration, and peer review sessions. The active learning component inherent in the flipped classroom approach ensures that students are not passive recipients of information but are actively constructing knowledge, thereby deepening their understanding and retention of writing principles (Akçayır & Akçayır, 2018; Bishop & Verleger, 2013; DeLozier & Rhodes, 2017). Furthermore, this integrated approach provides a framework for continuous feedback and revision, which is critical for writing development and cognitive growth. Students learn to view feedback not as criticism but as a valuable part of the learning process, encouraging a growth mindset and resilience (Burgess et al., 2020).

By creating a more personalised, interactive, and process-oriented learning experience, these integrated approaches not only prepare students for academic success but also equip them with the critical thinking, problem-solving, and creative skills necessary for professional and personal growth (Bernacki et al., 2021; Bulger, 2016; Grant & Basye, 2014; Shemshack et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2020). Holistic integration to writing instruction underscores the importance of adopting innovative educational practices that respond to the diverse needs of students within the demands of the 21st-century landscape.

The educational landscape is replete with innovative instructional strategies designed to enhance learning outcomes and foster cognitive development. Among these, the process writing approach, flipped learning, and the integration of HOTS stand out as particularly effective ways for improving students' writing skills and HOTS abilities. Individually, each of these approaches has been subject to extensive research, demonstrating respective benefits in educational settings. However, the literature reveals a noticeable research gap when it comes to examining the synergistic effects of combining these strategies. Even though combining the process writing approach, flipped learning, and HOTS might theoretically lead to better learning outcomes, there are not many empirical studies that look at how they affect students' writing performance and cognitive development as a whole. This study aims to address this gap by investigating the combined influence of these instructional approaches on students' performance in writing extended essays and their HOTS abilities. By exploring how these approaches interact and complement each other, the research seeks to provide a comprehensive understanding of their potential to jointly improve writing performance and HOTS.

Table 1 summarises the conceptual framework underpinning this study. It illustrates how these constructs inform the instructional design and expected learning outcomes of the intervention.

Table 1

Conceptual Framework of the Study

| Construct | Source | Key ideas | Role in study |

| Process writing approach | Flower & Hayes (1981); Graham & Sandmel (2011); Seow (2002) | Writing as a recursive, multi-stage process involving prewriting, drafting, revising, editing, and publishing. | Forms the basis for writing instruction in the experimental group. |

| Flipped learning | Bishop & Verleger (2013); Bergman & Sams (2023); Tucker (2017) | Content is delivered before class; class time is used for engaging activities. | Used to maximise student engagement with writing processes. |

| HOTS | Anderson & Krathwohl (2001); Brookhart (2010) | Focus on analysing, evaluating, and creating. | Skills integrated in the steps of writing according to genres. |

| Synergistic integration | Bielinska (2015); Burgess et al. (2020); Lee (2020) | Combining flipped learning and process writing promotes active engagement and cognitive development. | Explored as an innovative intervention strategy. |

Note. HOTS = Higher order thinking skills.

This study employed a quasi-experimental design to investigate the effects of integrating the process writing approach and flipped learning on students' extended essay writing performance and the development of HOTS. A quasi-experimental design, characterized by the absence of random assignment, was chosen for its practical applicability in educational settings where randomly assigning students to conditions is often not feasible or ethical. This design is suitable for educational research as it allows for the examination of instructional interventions in real-world classroom settings. According to Cook and Campbell (1979), quasi-experimental designs can provide valuable insights into the effects of educational practices, despite potential challenges in controlling all confounding variables.

In this study, the quasi-experimental design involved the comparison of two groups. The experimental group received instruction through a combined approach of process writing and flipped learning in the form of activities. In contrast, the control group received textbook-based writing instruction in a flipped learning setting without the specific integration of the approaches as experienced by the experimental group. Both groups were selected from similar educational backgrounds to ensure comparability and avoid bias. The following measures were addressed to mitigate potential validity threats inherent in quasi-experimental designs. Both groups went through pre-test and post-test assessments to measure their essay writing performance and HOTS development. This will help in determining the changes attributable to the intervention. Advanced statistical technique, such as analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was employed to adjust for any initial differences between groups, enhancing the credibility of the findings.

The sample consisted of Form Four students—16-year-old secondary school students (equivalent to Grade 10 internationally)—sourced from daily secondary schools in Malaysia. In this context, English language is a compulsory subject and writing extended essays is a compulsory sub-section of the writing requirements. The study followed Creswell's (2014) guidelines for a quasi-experimental design, which emphasise clear selection criteria, demographic characteristics, and a description of the context. Eligibility for participation hinged on registration as a Form Four student, willingness to engage in the study, and access to the Internet resources necessary for the flipped learning aspect of the research.The researchers used convenience sampling to select participants for this study. Convenience sampling was chosen because it allowed the researchers to select participants based on their availability and willingness to participate in the study, making it a practical and efficient method given the constraints of time and resources (Emerson, 2021; Raman et al., 2015). A total of 120 students, consisting of 45 males and 75 females, were chosen for the study. The control group consisted of 65 students, whereas the experimental group had 55 students. The control group was exposed to a textbook-based instruction in the form of flipped learning, whereas the experimental group was exposed to flipped learning-based process writing activities.

The researchers developed flipped learning-based process writing activities for an eight-week intervention. A total of 40 lessons in the form of units were taught, covering various aspects of writing such as prewriting, drafting, revising, editing, and publishing. The researchers assessed the participants' writing performance before and after the intervention through pre-test and post-test writing tasks. The Malaysia Examination Syndicate created a rubric with construct such as content, communicative achievement, organisation, and language for assessing extended essay writing performance and it was used in this study. This rubric offers a standardised approach for determining writing quality, facilitating objective scoring of essays, and ensuring consistency across evaluations. In addition, students' HOTS were assessed using a rubric adapted from Brookhart (2010), targeting skills in analysing, evaluating, and creating. The rubric is geared toward appraising students' capabilities in using HOTS. These rubrics provided a good picture of how students were growing in these important cognitive areas, especially in analysing, evaluating, and creating. The dual assessments ensured a holistic evaluation of students' writing performance and higher-order thinking skills.

The experimental group received flipped learning-based process writing instruction and activities, integrating online videos, interactive slide decks, and worksheets for pre-class preparation. The process writing approach emphasises the circular nature of writing through multiple drafts. Flipped learning enabled students to access the online resources and offline materials before class to learn more and use what they had learned in-class. In contrast, the control group experienced flipped learning using textbook-based materials. They accessed digital PDF versions of the textbook for pre-reading but did not engage in structured writing stages or receive targeted feedback. In-class activities for the control group focused on general discussion and comprehension checks, without explicit scaffolding of writing tasks according to process writing. The intervention was carried out for eight weeks.

Quantitative data were collected via pre-test and post-test assessments to quantitatively measure students' writing performance and their HOTS development at the beginning and end of the study period. Additionally, qualitative data were gathered through student interview, aimed at capturing students' HOTS development and experiences of the instructional approaches employed. The comprehensive approaches to data collection were designed to provide a multifaceted understanding of the effects of the interventions on students' writing performance and HOTS, ensuring a well-rounded analysis of the outcomes.

Quantitative data from pre-test and post-test assessments were analysed using ANCOVA to compare the performance of the experimental and control groups, controlling for pre-intervention performance. Qualitative data related to HOTS development were analysed using techniques described by Merriam & Tisdell (2025): (1) transcripts were read and coded inductively, (2) meaningful units were grouped under initial codes, (3) categories were refined through iterative comparison, and (4) final themes were derived to reflect patterns in students' experiences related to HOTS development. This included thematic analysis of responses from interviews and an analysis of instructors’ observations. The goal was to identify patterns and themes related to how the instructional approaches influenced students' HOTS, providing a nuanced understanding of the intervention's effects. The combination of quantitative and qualitative methods provides a robust analysis of the effect of these approaches.

To examine how well the experimental and control groups did on the extended essay writing task, Cohen et al. (2018) suggests doing statistical tests to compare their scores on the pre-test and post-test. In accordance with established research practices, the results are presented as mean scores and standard deviations, and the analysis utilises ANCOVA, which adjusts for any initial differences between the groups at the baseline. The use of ANCOVA is a recommended practice in research as it considers any potential biases or confounding factors that may impact the results, thus strengthening the validity and reliability of the findings. The mean scores indicate the average performance of students in each group, with the standard deviations reflecting the variability of scores within each group.

Table 2

Analysis Results for Experimental and Control Groups

| Group | Group size | Pre-test mean (SD) | Post-test mean (SD) |

| Experimental | 55 | 65 (8.56) | 85 (8.23) |

| Control | 65 | 71 (9.21) | 75 (10.11) |

The statistical analysis still indicates a statistically significant difference in the post-test scores between the experimental and control groups, F(1, 118) = 22.35, p < 0.001, with a medium effect size (Partial η2 = 0.18). The intervention significantly enhances the students' performance in extended essay writing. The mean scores and standard deviations, along with the adjusted group sizes, underscore that the students in the experimental group not only significantly improved in their essay writing performance post-intervention but also exhibited less variability in their performance outcomes compared to the control group. This suggests the educational intervention's positive and uniform impact across the experimental group. The ANCOVA test results reveal the statistical significance of differences between the groups while controlling for initial performance levels.

For each component, an ANCOVA test was conducted to adjust for initial differences and compare the mean post-test scores between the experimental and control groups, using pre-test scores as the covariate. The ANCOVA results summary applies to all components:

The results of the detailed analysis demonstrate a significant improvement in all four components of essay writing for the experimental group post-intervention as compared to the control group (Table 3). The statistical values, including the F-values and p-values, indicate a strong level of significance for each component, with effect sizes indicating a medium impact of the intervention. These findings highlight the effects of the intervention in enhancing students' overall essay writing performance. Moreover, the use of rigorous statistical analysis adds credibility to the validity of the results. Overall, this study contributes to the existing literature on essay writing interventions and emphasises the importance of targeted instruction in promoting students' writing performance.

Table 3

Four Constructs of Essay Writing Performance

| Component | Group | Pre-test mean (SD) | Post-test mean (SD) |

| Content | Experimental | 67 (10.1) | 85 (8.75) |

| Control | 65 (7.95) | 75 (10.30) | |

| Communicative achievement | Experimental | 62 (9.45) | 83 (7.70) |

| Control | 65 (8.77) | 74 (9.28) | |

| Organisation | Experimental | 69 (9.68) | 84 (8.68) |

| Control | 67 (9.35) | 73 (9.66) | |

| Language | Experimental | 71 (9.68) | 82 (7.68) |

| Control | 70 (8.37) | 72 (9.52) |

The findings of this study present compelling evidence for the effectiveness of the combined use of the process writing and flipped learning approaches in improving overall essay writing performance. Specifically, the intervention has been shown to positively impact content development, communicative efficiency, organisational skills, and language use in writing. These results suggest that the implementation of such instructional approaches may hold great promise in optimising writing instruction, as they promote the multifaceted enhancement of writing skill. Therefore, it is recommended that educators consider incorporating these approaches into their writing instruction and further exploring their potential for fostering holistic writing performance.

The qualitative analysis employed thematic analysis techniques, focusing on students' interview responses. The methods outlined by Merriam and Tisdell (2025) guided the coding process, enabling the identification of recurring themes and patterns related to the development of HOTS among participating students. The analysis of these themes and patterns provided valuable insights into the effects of the intervention. One of the most notable improvements reported by students after the implementation of the combined approaches was an enhanced ability to critically analyse texts. This was evident in their essays, demonstrating a deeper insight and a more sophisticated understanding of the material. Additionally, participants noted a significant increase in their problem-solving skills, as they felt better equipped to tackle complex questions and integrate their solutions into their written work. Furthermore, the incorporation of both approaches seemed to foster creative skill in students, leading to original thinking and the presentation of unique arguments in their essays. Another important aspect of the HOTS displayed was students’ newfound confidence in constructing and defending arguments, a recurring theme among participants. These reflect the success of the combined approaches in promoting students' HOTS abilities to not only form their own viewpoints but also evaluate and counter opposing perspectives.

Table 4 reflects core aspects of HOTS themes: analyzing, evaluating, and creating (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001), suggesting that the integrated approach supports cognitive skill development.

Table 4

Themes From Qualitative Interviews on HOTS Development

| Theme | Description | Illustrative quote |

| Critical analysis | Students showed improved ability to break down writing prompts and source material. | “Now I can identify what is really asked in the essay and focus my arguments better.” |

| Problem solving | Increased confidence in tackling complex essay tasks and finding relevant ideas. | “I used to get stuck halfway... now I plan and connect ideas more easily.” |

| Creativity | Ability to generate original arguments and writing styles. | “I like that we can rewrite and try again. I became more confident to write my own ideas.” |

| Argumentation & evaluation | Greater skill in organizing points and evaluating opposing views. | “We had to think if our points make sense and explain clearly why we chose them.” |

Instructors have reported a palpable shift, with students demonstrating higher critical thinking toward the course content in every phase of the process writing. This has been reflected in the quality of class discussions, where students have displayed a more insightful and analytical approach. Additionally, there has been a discernible improvement in the depth and quality of peer feedback, with students exhibiting proficiency in offering constructive critiques that reflect HOTS. These include the identification of logical fallacies, proposing alternative interpretations, and suggesting strategies for stronger argumentation. Such improvements in critical thinking and peer feedback skills have proven to be valuable in enhancing the overall student learning experience.

This study aimed to assess the effects of integrating the process writing approach with flipped learning on students' extended essay writing performance and development of HOTS. The findings from both quantitative and qualitative analyses offer strong support for the intervention’s effectiveness.

Quantitative results revealed statistically significant gains for the experimental group in all four essay writing components—content, communicative achievement, organisation, and language. The ANCOVA tests showed medium effect sizes (η2 = 0.17 to 0.18), indicating a consistent and meaningful improvement across writing domains. These results align with prior research affirming that structured, scaffolded writing processes improve writing performance (Graham & Sandmel, 2011; Seow, 2002).

Qualitative results complemented these findings. Students reported increased analysing, evaluating, and creating abilities which are key indicators of HOTS. Thematic analysis identified four major areas of growth—critical analysis, problem solving, creativity, and argumentation—reflecting students’ deeper engagement with writing as a cognitive task, not just a linguistic focused task.

The synthesis of results suggests that flipped learning enables learners to access foundational writing concepts before class, while in-class activities guided by the process writing approach create opportunities for applying, refining, and expanding these ideas. The iterative feedback comprising peer review, self-evaluation, and teacher feedback is instrumental in helping students develop metacognitive awareness of their writing and thinking processes.

Additionally, instructors’ observations confirmed students’ increased independence, reflective thinking, and peer engagement, reinforcing the interview data and providing further evidence of HOTS development. These observations highlight how instructional design based on Bloom’s revised taxonomy can lead to not only academic improvement but also cognitive transformation.

Overall, the study demonstrates that combining flipped learning with process writing offers a powerful model for enhancing both writing performance and higher-order thinking in ESL writing contexts. This dual-focus approach is particularly relevant in preparing 21st-century learners to be effective communicators and critical thinkers.

While this study yielded promising results, several limitations should be acknowledged. The relatively small and homogeneous sample may limit the generalizability of findings to other educational contexts. The eight-week intervention period, though adequate for observing short-term gains, may not reflect long-term skill retention. Additionally, the instruments used in this study, though validated, may not capture the full range of writing and thinking competencies developed during the intervention. Furthermore, the qualitative component relied on student self-report, which, while valuable, is inherently subjective. Instructor bias and implementation fidelity could have also influenced outcomes.

Future research should explore the scalability of flipped-based process writing instruction across different educational levels, subjects, and learner demographics. Longitudinal studies can assess the sustained impact of such interventions on writing performance and critical thinking. Researchers are also encouraged to compare different approaches for ESL writing context. The role of self-regulated learning strategies within this framework may also warrant exploration. Additionally, with the increasing integration of artificial intelligence in education, future studies could examine how AI-based writing tutors, chatbots, or adaptive feedback systems can complement or enhance flipped-based process writing instruction. This could open new pathways for personalised and scalable learning interventions. Broader investigations into student motivation, self-efficacy, and engagement in flipped-based writing classrooms would provide a more holistic picture of learning outcomes.

The integration of flipped learning and the process writing approach significantly improved both extended essay writing performance and HOTS among Malaysian Form Four ESL students. Quantitative data showed consistent improvement across all writing constructs, i.e., content, organisation, communicative achievement, and language. Qualitative data reinforced these outcomes, highlighting student growth in analysis, evaluative, and creative thinking. This synergy of approaches aligns with Bloom's revised taxonomy and supports student-centred, recursive and reflective learning. Importantly, the study demonstrates that when students engage with foundational writing concepts and apply them collaboratively during class, they achieve higher quality writing and deeper cognitive processing.

This integration of approaches is especially relevant, where students must be prepared to think critically and write effectively. Educators and curriculum designers are encouraged to adopt and adapt these blended instructional approaches to support students’ academic and cognitive development. The study offers practical evidence for the value of integrating structured writing processes with flipped learning, especially in ESL and high stakes writing contexts.

The authors acknowledge the use of ChatGPT v.4, a language model developed by OpenAI. We edited the language of this article as necessary through it and take full responsibility for it.

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Akçayır, G., & Akçayır, M. (2018). The flipped classroom: A review of its advantages and challenges. Computers & Education, 126, 334-345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.07.021

Allmendinger, P. (2017). Planning theory. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Alodwan, T. A. A., & Ibnian, S. S. K. (2014). The effect of using the process approach to writing on developing university students' essay writing skills in EFL. Review of Arts and Humanities, 3(2), 139-155. https://rah.thebrpi.org/journals/rah/Vol_3_No_2_June_2014/11.pdf

Amiryousefi, M. (2019). The incorporation of flipped learning into conventional classes to enhance EFL learners' L2 speaking, L2 listening, and engagement. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 13(2), 147-161. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2017.1394307

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (Eds.). (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom's taxonomy of educational objectives. Longman.

Bayat, N. (2014). The effect of the process writing approach on writing success and anxiety. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 14(3), 1133-1141.

Bean, J. C., & Melzer, D. (2021). Engaging ideas: The professor's guide to integrating writing, critical thinking, and active learning in the classroom. John Wiley & Sons.

Bereiter, C., & Scardamalia, M. (1987). The psychology of written composition. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bergmann, J., & Sams, A. (2023). Flip your classroom: Reach every student in every class every day (Rev. ed.). ASCD.

Bernacki, M. L., Greene, M. J., & Lobczowski, N. G. (2021). A Systematic Review of Research on Personalised Learning: Personalised by whom, to what, how, and for what purpose(s)? Educational Psychology Review, 33, 1675-1715. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09615-8

Bielińska-Kwapisz, A. (2015). Impact of writing proficiency and writing center participation on academic performance. International Journal of Educational Management, 29(4), 382-394. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijem-05-2014-0067

Bishop, J., & Verleger, M. A. (2013). The flipped classroom: A survey of the research. 2013 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, 23.1200.1-23.1200.18. https://peer.asee.org/22585

Bond, M. (2020). Facilitating student engagement through the flipped learning approach in K-12: A systematic review. Computers & Education, 151, 103819. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.103819

Brame, C. J. (2013). Flipping the classroom. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching.

Brookhart, S. (2010). How to Assess Higher-Order Thinking Skills in Your Classroom. ASCD.

Bulger, M. (2016). Personalised learning: The conversations we're not having. Data&Society, 22(1), 1-29. https://www.datasociety.net/pubs/ecl/PersonalizedLearning_primer_2016.pdf

Burgess, A., van Diggele, C., Roberts, C., & Mellis, C. (2020). Feedback in the clinical setting. BMC Medical Education, 20(2), 460. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02280-5

Campbell, D. T., & Cook, T. D. (1979). Quasi-experimentation. Chicago, IL: Rand Mc-Nally, 1(1), 1-384.

Campillo-Ferrer, J. M., & Miralles-Martínez, P. (2021). Effectiveness of the flipped classroom model on students' self-reported motivation and learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 8, 176. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00860-4

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2017). Research Methods in Education (8th ed.). London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315456539

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Educational research: Planning, conducting and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. Pearson.

Deane, P., Odendahl, N., Quinlan, T., Fowles, M., Welsh, C., & Bivens‐Tatum, J. (2008). Cognitive models of writing: Writing proficiency as a complex integrated skill. ETS Research Report Series, 2, i-36. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2333-8504.2008.tb02141.x

DeLozier, S. J., & Rhodes, M. G. (2017). Flipped classrooms: A review of key ideas and recommendations for practice. Educational Psychology Review, 29(1), 141-151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9356-9

Dörnyei, Z., & Muir, C. (2019). Creating a motivating classroom environment. In Second handbook of English language teaching (pp. 719-736). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Emerson, R. W. (2021). Convenience sampling revisited: Embracing its limitations through thoughtful study design. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 115(1), 76-77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145482X20987707

Faraj, A. K. A. (2015). Scaffolding EFL Students' Writing Through the Writing Process Approach. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(13), 131-141. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1080494.pdf

Flower, L., & Hayes, J. R. (1981). A cognitive process theory of writing. College Composition & Communication, 32(4), 365-387. https://doi.org/10.58680/ccc198115885

Graham, S., & Sandmel, K. (2011). The Process Writing Approach: A Meta-Analysis. The Journal of Educational Research, 104(6), 396-407. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2010.488703

Grant, P., & Basye, D. (2014). Personalised learning: A guide for engaging students with technology. International Society for Technology in Education.

Harris, S. G. K. R. (2023). The role and development of self-regulation in the writing process. In Self-regulation of learning and performance (pp. 203-228). Routledge.

Hava, K. (2021). The effects of the flipped classroom on deep learning strategies and engagement at the undergraduate level. Participatory Educational Research, 8(1), 379-394. https://doi.org/10.17275/per.21.22.8.1

Hayes, J. R., & Flower, L. S. (2016). Identifying the organisation of writing processes. In Cognitive processes in writing (pp. 3-30). Routledge.

Hyland, K. (2007). Genre pedagogy: Language, literacy and L2 writing instruction. Journal of Second Language Writing, 16(3), 148-164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2007.07.005

Karabulut‐Ilgu, A., Cherrez, N. J., & Jahren, C. T. (2017). A systematic review of research on the flipped learning method in engineering education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 49(3), 398-411. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12548

Lage, M. J., Platt, G. J., & Treglia, M. (2000). Inverting the classroom: A gateway to creating an inclusive learning environment. The Journal of Economic Education, 31(1), 30-43. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220480009596759

Lee, R. S. P. (2020). Exploring the learning outcomes of flipped learning in a Second Language (L2) academic writing classroom for low proficiency pre-university students. [Doctoral thesis, Swinburne University of Technology]. https://doi.org/10.25916/sut.26282392.v1

Nabhan, S. (2019). Bringing multiliteracies into process writing approach in ELT classroom: Implementation and reflection. Edulite: Journal of English Education, Literature, and Culture, 4(2), 156. https://doi.org/10.30659/e.4.2.156-170

Nerantzi, C. (2020). The use of peer instruction and flipped learning to support flexible blended learning during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Management and Applied Research, 7(2), 184-195. https://doi.org/10.18646/2056.72.20-013

Onozawa, C. (2010). A study of the process writing approach. Research Note, 10, 153-163.

Quan, J.-C., Luo, C., Yang, F., & Qiu, H.-P. (2017). Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives in information system courses. DEStech Transactions on Social Science, Education and Human Science, mess. https://doi.org/10.12783/dtssehs/mess2016/9623

Raman, A., & Thannimalai, R. (2021). Factors Impacting the Behavioural Intention to use e-Learning at Higher Education Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: UTAUT2 Model. Psychological Science and Education, 26(3), 82-93. https://doi.org/10.17759/pse.2021260305

Raman, A., Mey, C. H., Don, Y., Daud, Y., & Khalid, R. (2015). Relationship Between Principals' Transformational Leadership Style and Secondary School Teachers' Commitment. Asian Social Science, 11(15). https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v11n15p221

Raman, A. N., Thannimalai, R., Rathakrishnan, M., & Ismail, S. N. (2022). Investigating the influence of intrinsic motivation on behavioral intention and actual use of technology in Moodle platforms. International Journal of Instruction, 15(1), 1003-1024. https://doi.org/10.29333/iji.2022.15157a

Schoonen, R., van Gelderen, A., Stoel, R. D., Hulstijn, J. H., & De Glopper, K. (2011). Modeling the development of L1 and EFL writing proficiency of secondary school students. Language Learning, 61(1), 31-79. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2010.00590.x

Scott, B., & Vitale, M. R. (2003). Teaching the Writing Process to Students With LD. Intervention in School and Clinic, 38(4), 220-224. https://doi.org/10.1177/105345120303800404

Seow, A. (2002). The writing process and process writing. In J. C. Richards & W. A. Renandya (Eds.), Methodology in Language Teaching: An Anthology of Current Practice (pp. 315-320). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667190.044

Shemshack, A., Kinshuk, & Spector, J. M. (2021). A comprehensive analysis of personalised learning components. Journal of Computers in Education, 8, 485-503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40692-021-00188-7

Stefanou, C., & Xanthaki, H. (Eds.). (2016). Drafting legislation: A modern approach. Routledge.

Tisdell, E. J., Merriam, S. B., & Stuckey-Peyrot, H. L. (2025). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (5th ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Tucker, B. (2012). The flipped classroom. Education Next, 12(1), 82-83.

Yuliati, S. R., & Lestari, I. (2018). Higher-Order Thinking Skills (Hots) Analysis of Students in Solving HOTS Question in Higher Education. Perspektif Ilmu Pendidikan, 32(2), 181-188. https://doi.org/10.21009/pip.322.10

Zhang, L., Basham, J. D., & Yang, S. (2020). Understanding the implementation of personalised learning: A research synthesis. Educational Research Review (Print), 31, 100339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100339

Vanhitha Kernagaran is a PhD candidate in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) at Universiti Sains Malaysia in Malaysia. Her research focuses on enhancing extended writing performance and higher-order thinking skills through process writing and flipped learning approaches. Email: nithaakav@gmail.com ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5549-5384

Amelia Abdullah is a senior lecturer at the School of Educational Studies, Universiti Sains Malaysia in Malaysia. Her expertise includes teaching English to speakers of other languages (TESOL), educational technology and media, e-learning, language literacy, pedagogy, and computer-assisted instruction. Email: amelia@usm.my ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4055-699X