Lorelei Anselmo, University of Calgary, Canada

Sarah Elaine Eaton, University of Calgary, Canada

Postsecondary institutions increasingly recognize the importance of designing educational experiences that reflect students' diverse identities and life experiences. As online course enrollment continues to rise, it becomes crucial to address how course design can effectively support this diverse student population. Traditional course designs often fail to accommodate the broad spectrum of student backgrounds, resulting in barriers to success and inclusion. In response to this gap, we propose a framework for online course design that prioritizes inclusivity, flexibility, and ethical considerations. This three-layer framework systematically integrates Universal Design for Learning principles with academic integrity values and Indigenous academic integrity principles, providing educators with practical guidance to create ethical and supportive online learning environments that address learner agency while maintaining academic standards.

Keywords: academic integrity, blended learning, equity, inclusion, online, teaching, universal design for learning

Les établissements d'enseignement postsecondaire reconnaissent de plus en plus l’importance de concevoir des expériences d’enseignement qui reflètent la diversité des identités et des expériences de vie des personnes étudiantes. Alors que les inscriptions aux cours en ligne continuent d’augmenter, il devient essentiel de se pencher sur la façon dont la conception des cours peut soutenir efficacement cette population étudiante diversifiée. La conception traditionnelle des cours ne tient souvent pas compte de la grande diversité des parcours des personnes étudiantes, ce qui crée des obstacles à la réussite et à l’inclusion. Pour combler cette lacune, nous proposons un cadre de conception des cours en ligne qui priorise l’inclusivité, la flexibilité et les considérations éthiques. Ce cadre à trois niveaux intègre systématiquement les principes de la conception universelle de l’apprentissage aux valeurs d’intégrité académique et aux principes d’intégrité académique autochtones, fournissant ainsi aux personnes enseignantes des orientations pratiques pour créer des environnements d’apprentissage en ligne éthiques et de soutien qui favorisent l’autonomie des personnes étudiantes tout en maintenant les exigences académiques.

Mots-clés : intégrité académique, cours hybrides, équité, inclusion, en ligne, enseignement, conception universelle de l’apprentissage

In their spring survey, the Canadian Digital Learning Research Association (2024) reported that 100 of the 132 participating postsecondary institutions stated they expected growth in hybrid offerings (courses offered with a blend of online and in-person instruction), and 83 anticipated growth in fully online offerings (all instruction and interaction is entirely online). With this growth comes increased assumptions and misconceptions regarding academic integrity in online learning.

Although research exists about the benefits and challenges of online learning for educators, students, and institutions, there is less research about academic integrity in online course design and the use of technology (Bretag, 2019; Canadian Digital Learning Research Association, 2024; Eaton, 2021). Here we synthesize evidence-informed practice integrating the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework (CAST, 2025), UDL-based online course design considerations (Rao, 2021), and academic integrity.

This work began as a workshop series we co-developed and facilitated at a western Canadian institution (Anselmo & Eaton, 2023). Throughout the design process, we discussed how UDL principles implicitly include aspects of academic integrity, yet we found limited research or practice-oriented resources making these connections explicit. We wanted to explore how UDL and academic integrity could be systematically integrated into online course design.

Our proposed framework differs from existing approaches by creating intentional synergies between UDL principles and academic integrity values specifically tailored for online environments. While UDL frameworks exist for online learning and academic integrity policies address student conduct, to our knowledge, no previous work has systematically integrated these approaches to address the unique challenges of ethical online course design. This layered approach provides several advantages over using individual frameworks: (a) it ensures that accessibility and inclusion efforts align with academic standards, (b) embeds ethical considerations into instructional design from the outset rather than as an afterthought, and (c) creates coherent support systems that address learner agency, variability, and academic integrity simultaneously. The result is a more comprehensive approach to online course design that positions ethics and inclusion as complementary rather than competing priorities.

Universal design for learning is a framework that can guide the development of inclusive learning environments to support all students (CAST, 2025). A 2019 survey of first-year undergraduate students in Canadian postsecondary institutions indicated that 44% identified as from an equity-deserving group, while 24% reported having a disability (Usher, 2021). The UDL framework can serve as a model to support postsecondary instructors in their instructional design to help best meet students’ diverse learning needs and position them as successful learners.

The UDL framework includes three grounding principles: designing for multiple means of engagement, multiple means of representation, and multiple means of action and expression (CAST, 2025). These principles may offer an instructional design model for educators to strive for inclusive, flexible, and ethical learning environments for their students based on how instructional material is presented, how students demonstrate their learning, and how they are engaged throughout their learning (CAST, 2025). Dwyer-Kuntz (2022) points out that the primary objective of UDL is to reduce barriers to empower learners to reach their maximum potential; while CAST (2025) refers to learner agency as a goal where students become intentional, authentic, and strategic in their learning. We propose that reducing barriers supports the development of learner agency and becomes a particularly important component of course design in the online learning environment where technology and access are key considerations for learner success. Applying the three UDL principles to online learning may enhance student learning by integrating learning technologies that support learner inclusivity, and provide flexible pathways for students to learn in an ethical environment (Basham et al., 2020; Rao, 2021; Zhu et al., 2024). In online environments, these UDL principles address specific challenges: (a) multiple means of representation accommodate diverse ways learners perceive information (e.g., audio, visual, and text formats); (b) multiple means of action and expression recognize different skill sets for navigating and demonstrating knowledge (e.g., oral presentations, infographics); and (c) multiple means of engagement sustain motivation through varied opportunities that reflect learners' interests and identities (CAST, 2025). The three UDL principles, grounded in addressing learning variability, learner agency, and reducing barriers to learning, can be integrated through intentional and proactive online course design (Rao, 2019).

Centring intentional and proactive online course design around learner variability, learner agency, and reducing barriers to learning highlights the student as a complex learner who needs to balance their preferences and desire to learn within the boundaries and systems of an educational institution. How students approach this balance may be influenced by their values and principles (Clark et al., 2020). We position the UDL framework (CAST, 2025) and the values of academic integrity (ICAI, 2021) with Indigenous academic integrity principles (Gladue, 2020) as a layered approach for intentional online course design that is inclusive, flexible, and holistic for students.

Existing UDL applications to online learning focus primarily on accessibility and learning variability but rarely address the ethical dimensions of course design. Similarly, academic integrity frameworks concentrate on student conduct rather than instructional design decisions. This creates a gap where well-intentioned accessibility efforts may inadvertently undermine academic standards, or where academic integrity policies may create barriers for diverse learners. Our integrated approach addresses this gap by demonstrating how ethical considerations can strengthen rather than conflict with inclusive design principles.

To ensure clarity and consistency throughout this framework, we define the following key terms:

Universal Design for Learning. A framework that guides the development of flexible learning environments and spaces that can accommodate individual learning differences, based on three principles: multiple means of engagement, representation, and action and expression (CAST, 2025).

Acadmic Integrity. The commitment to fundamental values including honesty, trust, fairness, respect, responsibility, and courage in academic work and scholarly practice (ICAI, 2021). We also recognize Indigenous academic integrity principles of relationality and reciprocity (Gladue, 2020).

Ethics in Online Course Design. The intentional integration of moral principles and values into instructional design decisions, ensuring courses support student learning while maintaining academic standards and promoting equity.

Flexibility. The provision of multiple pathways, options, and supports that allow students to engage with content, demonstrate learning, and participate in courses in ways that align with their individual needs, circumstances, and strengths.

Online Learning Environment. Educational settings where instruction and interaction occur primarily through digital platforms and technologies, requiring specific design considerations for accessibility, engagement, and academic integrity.

Learner Agency. The development of students who are purposeful and reflective in their thinking, resourceful and authentic in their approach, and strategic and action-oriented in their learning (CAST, 2025).

Values and principles have long been used to frame academic integrity. One globally dominant framework is the Fundamental Values of Academic Integrity (ICAI, 2021) which articulates these six values of academic integrity: courage, fairness, honesty, respect, responsibility, and trust. Although educators, academic integrity practitioners, and policymakers have adopted this values framework in many jurisdictions, it is not without its limitations or criticisms. For example, Indigenous and Métis scholars in Canada have pointed out that Indigenous ways of knowing, being, doing, and learning should be recognized and valued in their own right (Gladue, 2020; Lindstrom, 2022; Poitras Pratt & Gladue, 2022). Gladue (2020) highlights three principles of Indigenous academic integrity, focusing on relationality, reciprocity, and respect. Lindstrom (2022) notes that, “the notion of integrity is holistic, which means it is infused in all areas of life” (p. 126) and asserts that, “the ways postsecondary institutions translate and mobilize academic integrity equates to complicity in ongoing colonization and disrupts institutional efforts aimed at Indigenization and decolonization” (p. 127). An in-depth discussion of such complicity is beyond the scope of this article; however, we note the wisdom in Poitras Pratt and Gladue’s (2022) assertion that Western and Indigenous values and principles can be complementary and parallel, rather than contrary to one another. Poitras Pratt and Gladue assert that “parallel ways of expressing and centering truth are essential to the work of redefining academic integrity for all because they challenge the oft (consciously or unconsciously) held belief that western axiology and ethics are the pinnacle and definition of truth in academic culture” (2022, p. 115). This parallel approach recognizes that Indigenous and Western integrity frameworks can enhance rather than compete with each other in educational contexts. For example, the ICAI value of respect aligns with and is enriched by Indigenous principles of relationality, creating a deeper understanding of how academic work connects individuals to broader communities. The Western emphasis on individual responsibility finds complementary expression in Indigenous concepts of reciprocity, which emphasize our obligations to give back to the knowledge communities that support our learning. Rather than requiring choice between frameworks, our layered approach demonstrates how these parallel ways of understanding integrity can strengthen online course design by providing multiple entry points for students to connect with ethical academic practices.

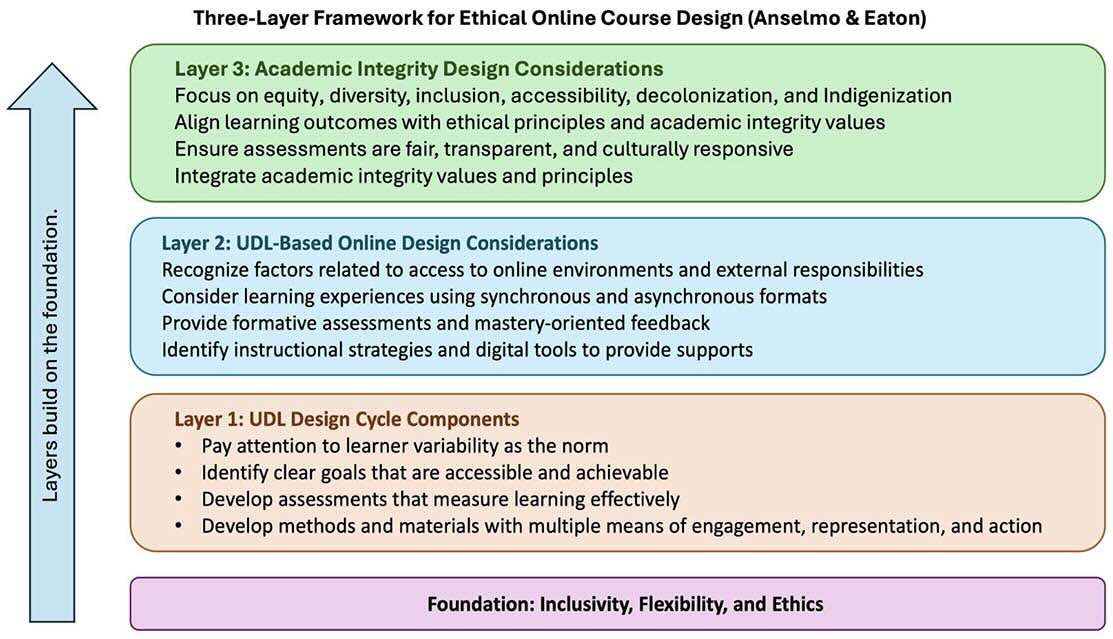

Complementary and parallel ways of knowing that include a plurality of values and principles can underpin our understanding of academic integrity. The UDL framework is applied to educational purposes to reduce the “learning barriers that occur as an interaction between learners’ strengths, challenges, and preferences” (Basham et al., 2020, p. 810). The framework has been applied in various contexts, including accessibility, technology, and blended and online learning (Basham et al., 2020; Celestini & Palalas, 2024). Our conceptual framework is a three-layer approach to inclusive, flexible, and ethical online course design (Table 1).

Table 1

Layering of UDL-Based Online Design With Academic Integrity

| Design layer | Learner experience | Learning goals | Assessment | Materials and methods |

| UDL design cycle considerations (Rao & Meo, 2016) | Pay attention to learner variability. | Identify clear goals. | Develop assessments. | Develop methods and materials. |

| UDL-based online design considerations (Rao, 2021) | Recognize factors related to access to online environments and the external responsibilities of learners. | Consider learning experiences that use synchronous and asynchronous formats. | Provide formative assessments and mastery-oriented feedback to clarify expectations. | Identify instructional strategies and digital tools to provide supports and reduce barriers. |

| Academic integrity considerations | Focus on equity, diversity, inclusion, accessibility, decolonization, and Indigenization as academic integrity and social justice priorities. | Align learning outcomes with course goals, program objectives, and assessments. Setting clear expectations for upholding academic integrity. | Ensure formative and summative assessments are fair and clearly explained. Ensure assessment criteria are transparent. | Ensure materials and methods are up-to-date, accessible, and relevant to the course assessments, learning outcomes, and program goals. |

Note. UDL = Universal Design for Learning

The first layer focuses on considerations for a UDL-based design: learner variability, clear goals, assessments, and methods and materials (Rao & Meo, 2016). The second layer incorporates UDL-based design considerations for the online learning environment: access, asynchronous and synchronous interactions, engagement and feedback, instructional strategies, and learning technology tools (Rao, 2019). Finally, the third layer incorporates academic integrity principles and values such as the fundamental values of academic integrity: honesty, trust, fairness, respect, responsibility, and courage (ICAI, 2021) and the Indigenous academic integrity principles: relationality and reciprocity (Gladue, 2020). Together, these layers form the foundation for a framework for online course design that has at its core inclusivity, flexibility, and ethics (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Three-Layer Framework for Ethical Online Course Design

Note. Figure created by the authors.

Universal design for learning can provide an inclusive instructional design framework when implemented as an iterative design cycle. Our approach emphasises three foundational UDL elements: flexibility (supporting iteration and responsiveness to diverse learner needs), clear goals (guiding purposeful planning and ensuring learner understanding), and aligned assessment (providing feedback loops that refine instruction throughout the cycle) (Rao, 2019).

Course design with UDL begins with learner variability as the norm, accommodating diverse abilities, backgrounds, and preferences (Getenet et al., 2024; Hart, 2010; Rose & Meyer, 1999; Zhu et al., 2024). This foundation supports clear goal setting, relevant assessments, and flexible methods that integrate multiple pathways for engagement, representation, and expression (Rao, 2019; Rao & Meo, 2016). Together, these four components may ensure that an online course is designed with UDL principles, including flexibility and inclusivity for all students. The next phase of our conceptual framework incorporates online learning environment design considerations.

The flexibility of UDL serves instructors across disciplines and modalities, particularly in online environments where technology access and digital literacy create unique barriers (Basham et al., 2020; Celestini & Palalas, 2024; Getenet et al., 2024; Rao, 2019; Trust & Pektas, 2018).

Online environments require specific adaptations of each UDL component. Clear goals must reflect chunked content delivery with multiple practice opportunities through institutionally supported learning management systems and digital tools (Rao, 2019). Assessment development focuses on supporting memory, generalization, and transfer through collaborative tools that facilitate multimodal feedback and foster instructor-student relationships (Flock, 2020; Rao, 2019; Trust & Pektas, 2018). Methods and materials selection prioritizes digital tools that align with UDL's three principles while centring learner needs in instructional design decisions (Celestini & Palalas, 2024; Wenzel & Moreno, 2022).

Designing assessments with ethical principles in mind, such as reciprocity (Gladue, 2020), transforms evaluation from individual measurement to community accountability. This shifts online assessment from isolated testing to collaborative learning that honors relationships and mutual responsibility.

Framing academic integrity through UDL means designing for learner agency (i.e., not policing students) so that ethical choices are supported at every step of the course. Through UDL’s three main categories, ethics can become an intentional design feature: (a) engagement (the why of learning)—recruit interest with relevant, choice-rich tasks, sustain effort with staged deadlines and feedback, and build self-regulation with time-management tools and brief reflections on tool use; (b) representation (the what of learning)—provide accessible materials, model citation and paraphrasing, translate policies into plain language, and acknowledge Indigenous knowledge protocols to make attribution practices explicit; and (c) action & expression (the how of learning)—offer multiple modes of demonstration under a shared rubric that emphasizes originality and attribution, require drafts and process notes, and support executive function with checklists, exemplars, and planning prompts (CAST, 2025; Gladue, 2020). Together, these design choices include ethics as an intentional part of online learning success.

When these UDL principles integrate with academic integrity values of courage, fairness, honesty, respect, responsibility, and trust (ICAI, 2021) alongside Indigenous principles of relationality and reciprocity (Gladue, 2020), online courses transform from spaces of surveillance to environments of ethical growth. For example, considering both the ICAI value of responsibility and Indigenous principles of reciprocity may involve designing assessments that ask students to seek knowledge from community members and share findings back with those communities in multiple formats (audio, written, or visual). This approach honors diverse communication strengths while embedding ethical community accountability into the learning process.

Intentional online course design that considers ethical values (ICAI, 2021) and Indigenous academic integrity principles (Gladue, 2020) in parallel with UDL considerations may serve as an ethical guide for instructors to design their online courses. Students develop agency not just as learners, but as ethical practitioners who understand how their academic work connects to broader communities and responsibilities.

An ethical online course design grounded in UDL principles requires more than inclusive intent: it becomes operational when learning outcomes explicitly foreground inclusivity, flexibility, and ethics, and when institutions provide sustained scaffolds—policy, resources, time, technology, and faculty development—to implement, evaluate, and refine those commitments. For example, intentionally designing ethical learning outcomes that reflect both academic integrity values and Indigenous principles of academic integrity may better support students in connecting with the content and becoming courageous learners.

Courage is often connected to academic integrity. In this sense, courage can refer to “being willing to take risks and risk failure” (ICAI, 2021, p. 10). In their role as educators, rather than an enforcer, the instructor creates connection and community with the students by designing this personalized space that includes supplementary resources and supports. Students who feel a sense of belonging through the online learning space may feel a sense of relationality or connection to the course and the instructor. In turn, this may impact how they make ethical decisions related to their learning (Gladue, 2020). In an inclusive, flexible, and ethical online learning space, learners can develop a sense of belonging, feel safe expressing their opinions, and have the courage to make mistakes without fearing punitive consequences.

Another UDL-based online design consideration relates to feedback (Rao, 2021). Ethical approaches to course learning outcomes could reflect academic integrity considerations regarding assessment and feedback. Clark et al. (2020) noted that in addition to postsecondary institutions’ goals of graduating students with the necessary skills and abilities required to begin careers in their fields, “an emerging priority is also to ensure that these graduates are ethical, contributing members of society” (p. 1). In this manner, ethical approaches to course learning outcomes could involve a more holistic and intentional approach to academic integrity by designing learning outcomes that focus on process versus product and integrate creativity and higher-order thinking skills. Taking this approach supports academic integrity values (ICAI, 2021), especially fairness, when assessing students, as well as the Indigenous academic integrity principle of respect in providing meaningful feedback that “connects to create new knowledge" (Gladue, 2020, p. 5). Including values such as fairness and respect explicitly in course learning outcomes may allow students to examine each value, reflect on their connection, and influence individual academic decisions regarding the course (Clark et al., 2020).

Ethical online course design is not a task to be completed, nor a checkbox to be ticked, but rather a long-term commitment enacted through regular and sustained practice. Designing ethical courses is not about getting it right the first time but rather committing to a continual and intentional process which is revised and refined over time. Creating inclusive, flexible, and ethical courses requires comprehensive institutional support across multiple domains. Essential formal support networks include collaboration with academic services units for accessibility accommodations and learning support; partnerships with instructional design teams for pedagogical consultation; coordination with information technology services for reliable technology infrastructure; and alignment with academic integrity offices for policy guidance and student education programs (Bertram Gallant, 2016; Bretag, 2016; Davis, 2022; Kenny & Eaton, 2022). Informal support networks are equally crucial, including communities of practice among faculty, mentorship programs for course design, and peer consultation opportunities for sharing effective strategies (Kenny & Eaton, 2022).

Institutional commitment must also address practical considerations such as adequate time allocation for thoughtful course development, professional development funding for UDL and academic integrity training, technology resources that support multiple learning modalities, and assessment practices that allow flexibility while maintaining rigor. Without this multi-layered institutional support, individual instructors face unrealistic expectations to implement comprehensive ethical course design within existing constraints.

Postsecondary students face challenges and incentives that previous generations of students did not (Usher, 2021). The onset of contract cheating companies, artificial intelligence applications, and external factors mean that our courses, especially our online courses, require a new approach that meaningfully and intentionally builds academic integrity values and principles into online course design.

We propose an ethical online course design framework that incorporates UDL considerations with academic integrity values (ICAI, 2021) and Indigenous academic integrity principles (Gladue, 2020) to highlight the following academic integrity online course considerations: ethical uses of learning technologies, ethical commitments to student learning, ethical approaches to course learning outcomes, and ethical commitments to student success. Ethical use of learning technologies is considered informed, transparent, ethical, and responsible use (Gutiérrez, 2023). Ethical commitments to student learning include creating an online learning space for courageous learning supported by committed instructors. Ethical approaches to course learning outcomes incorporate values and principles explicitly in the course learning outcomes so students can apply these values to their online academic decisions. Finally, ethical approaches for student success involve the institution supporting and assisting online students with policies and procedures that enhance and encourage ethical academic behaviour.

We offer recommendations for instructional design and pedagogy not in the form of prescriptive tasks or checkbox items because this would be antithetical to thoughtful and intentional course design. We also recognize that educators and learning designers in different jurisdictions may have varying levels of independence or constraints, which can impact their level of autonomy in their work. For these reasons, we offer recommendations in the form of points to consider and provocations in guided questions (Figure 2). Figure 2 employs a circular design to emphasize the iterative and interconnected nature of ethical course design. Unlike linear checklists that suggest a fixed sequence, the overlapping elements represent how these four considerations must be addressed simultaneously and revisited throughout course development. The visual metaphor reflects our framework’s core principle that ethical design emerges from continuous reflection rather than one-time implementation.

Figure 2

Recommendations for Pedagogy and Instructional Design

Note. Figure created by the authors.

Ethical UDL-aligned design requires transparency in technology choices, positioning instructors as coaches rather than enforcers, emphasizing process alongside product in assessments, offering flexible modalities mapped to consistent outcomes, framing academic integrity relationally, and maintaining visible supports with plain-language policies.

Layer 1 Application (UDL Design Cycle). The instructor recognizes learner variability by providing course content in multiple formats: recorded lectures with auto-generated captions and transcripts, interactive H5P modules with built-in accessibility features, and downloadable PDF summaries for offline reading. Clear goals are established through weekly learning objectives that scaffold toward larger course outcomes, with a visual progress tracker showing students their advancement. Assessments include options such as traditional written papers (1,500 words), video presentations (8–10 minutes), or research infographics with citations to accommodate different strengths and communication preferences.

Layer 2 Application (Online Considerations). Recognizing access barriers, the instructor provides both synchronous student hours via video conferencing and asynchronous discussion forums for questions. Technical support resources are prominently linked in the course menu, including video tutorials for accessing materials on low-bandwidth connections. Formative assessments include weekly discussion posts with peer responses and self-check quizzes with immediate explanatory feedback.

Layer 3 Application (Academic Integrity Integration). Learning outcomes explicitly include integrity values: “Students will demonstrate respect for diverse perspectives through thoughtful peer responses that acknowledge sources and build on others' ideas.” The major research assignment emphasizes process through required submission of research journals documenting source evaluation, interview notes from community conversations, and reflection on ethical considerations in psychological research. Students interview community members about mental health perspectives and must share their findings back with those communities, embodying reciprocity. The rubric transparently outlines expectations for original analysis while providing APA resources and citation tutorials.

Synergistic Result. A student can choose the video presentation format (Layer 1 accommodation) while participating asynchronously (Layer 2 consideration) and still engaging in community-based reciprocal learning that builds ethical research skills (Layer 3 integration). The accommodation enhances rather than undermines the ethical learning goals. This implementation requires institutional support through accessible technology infrastructure, instructor training time, and coordination with community partners, but leverages existing institutional resources rather than requiring entirely new systems.

We further offer reflecting questions for course developers recognizing that context and institutional guidelines impact course design choices.

One potential area of further research for classroom practical applications of the UDL framework includes investigating how applying the UDL framework in classes might facilitate “attitudinal change” and “develop inclusive values” amongst learners (Sewell et al., 2022, p. 374). We also recognize the immense impact generative artificial intelligence has had on online course design and acknowledge that this area is outside the scope of this paper.

Our conceptual framework layers 1) UDL design cycle components, 2) UDL-based online design considerations, and 3) academic integrity design considerations provide a basis for an ethical approach to online course design that considers the fundamental values of academic integrity (ICAI, 2021) in parallel with Indigenous academic integrity principles (Gladue, 2020).

An ethical online course design framework addresses the fundamental UDL goal of removing barriers to develop learner agency through inclusive, flexible, and ethical design while highlighting values and principles that support ethical online learning.

This conceptual framework presents several limitations that future work should address. First, as a theoretical model, it requires empirical testing to validate its effectiveness in improving student learning outcomes and reducing academic misconduct. Second, full implementation demands significant institutional resources including professional development time, technological infrastructure, and ongoing pedagogical support that may not be available to all educators. Third, the framework assumes instructors have sufficient autonomy to modify course design and assessment practices, which may not reflect the constraints faced by adjunct faculty or those in highly regulated programs. Fourth, while we have attempted to integrate Indigenous and Western approaches to academic integrity, this integration represents our interpretation and may not reflect the diversity of Indigenous perspectives across different communities. Finally, the framework's emphasis on community-based learning may not be appropriate for all disciplines or learning contexts, requiring adaptation that we have not fully explored.

We recognize that conceptual frameworks must be interrogated and tested. In this article, we have introduced a framework that can be used as a guide. By using this framework, instructors and course designers may be able to make more intentional decisions about integrating academic integrity values (ICAI, 2021) and Indigenous principles of academic integrity (Gladue, 2020) in their online courses and thereby design online courses which promote and develop ethical global citizens. However, the ultimate utility of the framework would be determined by testing, reflective and reflective pedagogical feedback, and revisions in future iterations. We offer the ethical online course design framework as a point of departure, rather than a destination, for intentional integration of UDL with academic integrity to promote inclusivity, flexibility, and ethical pedagogy.

Anselmo, L., & Eaton, S. E. (2023, April 27). Transforming academic integrity course design from reactive to proactive. [Conference session]. Conference on Postsecondary Teaching and Learning. Calgary, Alberta, Canada. https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1mJsLPcH6kw20EUueaYs1MkeDBZBZZSUs/edit?slide=id.p1#slide=id.p1

Basham, J. D., Blackorby, J., & Marino, M. T. (2020). Opportunity in Crisis: The Role of Universal Design for Learning in Educational Redesign. Learning Disabilities: A Contemporary Journal, 18(1), 71-91. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1264277

Bertram Gallant, T. (2016). Leveraging institutional integrity for the betterment of education. In T. Bretag (Eds.), Handbook of Academic Integrity. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-098-8_52

Bretag, T. (2019). From ‘perplexities of plagiarism’ to ‘building cultures of integrity’: A reflection on fifteen years of academic integrity research, 2003-2018 (pp. 5-35). HERDSA Review of Higher Education, 6. https://herdsa.org.au/herdsa-review-higher-education-vol-6/5-35

Canadian Digital Learning Research Association. (2024). 2024 Pan-Canadian Report on Digital Learning. https://cdlra-acrfl.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/2024-Pan-Canadian-Report_EN.pdf

Celestini, A., & Palalas, A. (2024). Inclusive Online Nursing Education: Learner Perceptions of Universal Design for Learning Approaches. The Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 15(3), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.5206/cjsotlrcacea.2024.3.16911

Center for Applied Special Technology. (2025). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines Version 3.0. https://udlguidelines.cast.org/

Clark, A., Goodfellow, J., & Shoufani, S. (2020). Examining academic integrity using course-level outcomes. Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 11(2). https://doi.org/10.5206/cjsotl-rcacea.2020.2.8508

Davis, M. (2022). Examining and improving inclusive practice in institutional academic integrity policies, procedures, teaching and support. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 18, 14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-022-00108-x

Dwyer-Kuntz, T. (2022). UDL in online learning — One size doesn’t fit all. In R. Kay & B. Hunter (Eds.), Thriving online: A guide for busy educators. eCampusOntario. https://doi.org/10.51357/ghkl9022

Eaton, S. E. (2021). Communities of Integrity: Engaging Ethically Online for Teaching, Learning, and Research [Closing keynote address]. European Conference on Academic Integrity and Plagiarism, Online. https://dx.doi.org/10.11575/PRISM/38918

Fiock, H. (2020). Designing a Community of Inquiry in Online Courses. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 21(1), 135-153. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v20i5.3985

Getenet, S., Cantle, R., Redmond, P., & Albion, P. (2024). Students’ digital technology attitude, literacy and self-efficacy and their effect on online learning engagement. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 21(3). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00437-y

Gladue, K. (2020). Indigenous Academic Integrity. Taylor Institute of Teaching and Learning, University of Calgary. https://taylorinstitute.ucalgary.ca/sites/default/files/Content/Resources/Academic-Integrity/21-TAY-Indigenous-Academic-Integrity.pdf

Gutiérrez, J. D. (2023). Guidelines for the Use of Artificial Intelligence in University Courses. Universidad del Rosario. https://forogpp.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/guidelines-for-the-use-of-artificial-intelligence-in-university-courses-v4.3.pdf

Hart, M. A. (2010). Indigenous worldviews, knowledge, and research: The development of an Indigenous research paradigm. Journal of Indigenous Voices in Social Work, 1(1A), 1-16. https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/jisd/article/view/63043

International Center for Academic Integrity (ICAI). (2021). The fundamental values of academic integrity (3rd ed.).

Kenny, N., & Eaton, S. E. (2022). Academic Integrity Through a SoTL Lens and 4M Framework: An Institutional Self-Study. In S. E. Eaton & J. Christensen Hughes (Eds.), Academic Integrity in Canada: An enduring and essential challenge (pp. 573-592). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-83255-1

Lindstrom, G. (2022). Ethical space of engagement in curriculum development processes: Indigenous guiding principles for curriculum development projects. Taylor I nstitute for Teaching and Learning, University of Calgary. https://taylorinstitute.ucalgary.ca/resources/indigenous-guiding-principles-for-curriculum-development-projects

Poitras Pratt, Y., & Gladue, K. (2022). Re-defining academic integrity: Embracing Indigenous truths. In S. E. Easton, J. Christensen Hughes. (Eds.). Academic Integrity in Canada. Ethics and Integrity in Educational Contexts. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-83255-1_5

Rao, K. (2019). Instructional design with UDL: Addressing learner variability in college courses. In S. Bracken, & K. Novak. (Eds.). Transforming higher education through universal design for learning: An international perspective. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351132077

Rao, K. (2021). Inclusive instructional design: Applying UDL to online learning. https://edtecharchives.org/journal/223/3753

Rao, K. & Meo, G. (2016). Using Universal Design for Learning to Design Standards-Based Lessons. SAGE Open, 6(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244016680688

Rose, D. (2000). Universal Design for Learning. Journal of Special Education Technology, (15)4, 47-51. https://doi.org/10.1177/016264340001500407

Sewell, A., Kennett, A., & Pugh, V. (2022). Universal Design for Learning as a theory of inclusive practice for use by educational psychologists. Educational Psychology in Practice, 3 8(4), 364-378. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2022.2111677

Trust, T., & Pektas, E. (2018). Using the ADDIE Model and Universal Design for Learning Principles to Develop an Open Online Course for Teacher Professional Development. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 34(4), 219-233. https://doi.org/10.1080/21532974.2018.1494521

Usher, A. (2021). The State of Postsecondary Education in Canada, 2021. Toronto: Higher Education Strategy Associates. https://higheredstrategy.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/HESA_SPEC_2021.pdf

Wenzel, A., & Moreno, J. (2022). Designing and Facilitating Optimal LMS Student Learning Experiences: Considering students’ needs for accessibility, navigability, personalization, and relevance in their online courses. The Northwest eLearning Journal, 2(1). 1-35. https://doi.org/10.5399/osu/nwelearn.2.1.5642

Zhu, M., Berri, S., Koda, R., & Wu, Y. (2024). Exploring students’ self-directed learning strategies and satisfaction in online learning. Education and Information Technologies, 29, 2787-2803. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-11914-2

Lorelei Anselmo, MEd, is the Teaching Supports Team Lead at the Taylor Institute for Teaching and Learning at the University of Calgary in Alberta, Canada. Her areas of interest include online and in-person course design and academic integrity in higher education. Email: lanselmo@ucalgary.ca ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3525-1227

Sarah Elaine Eaton is Professor in the Werklund School of Education at the University of Calgary in Alberta, Canada. Her research focuses on ethics and integrity in higher education. Email: seaton@ucalgary.ca ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0607-6287