Nadia Delanoy, University of Calgary, Canada

This mixed-methods study examined how experiential learning theory (ELT) can support the development of digital and artificial intelligence literacies in postsecondary education through the integration of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) tools. Guided by ELT’s four-stage cycle, concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation, and active experimentation, this study explored how students engaged with GenAI to enhance their learning, critical thinking, and ethical awareness. Data were collected from 17 students and one instructor through surveys and semi-structured interviews. Descriptive and thematic analyses revealed that students initially identified as beginners in GenAI use, employing the technology primarily for functional tasks such as organizing information or conducting surface-level research. Through experiential engagement and guided reflection, students demonstrated growth in confidence, ethical understanding, and critical evaluation of AI-generated outputs. Instructor findings converged with student perspectives, emphasizing the value of scaffolded, reflective engagement for literacy development. The integration of quantitative and qualitative results underscored the effectiveness of experiential learning in a GenAI-designed course.

Keywords: artificial intelligence literacy, ethics, experiential learning theory, digital literacy, generative artificial intelligence

Cette étude à méthodes mixtes a examiné la façon dont la théorie de l’apprentissage expérientiel (AE) peut soutenir le développement de la littératie numérique et la littératie en intelligence artificielle dans l’enseignement supérieur grâce à l’intégration d’outils d’intelligence artificielle générative (IAg). Guidée par le cycle en quatre étapes de l’AE, à savoir l’expérience concrète, l’observation réfléchie, la conceptualisation abstraite et l’expérimentation active, cette étude a exploré la manière dont les personnes étudiantes ont utilisé l’IAg pour améliorer leur apprentissage, leur esprit critique et leur conscience éthique. Les données ont été recueillies auprès de 17 personnes étudiantes et d’une personne enseignante à l’aide de sondages et d’entretiens semi-structurés. Des analyses descriptives et thématiques ont révélé que les personnes étudiantes initialement identifiées comme débutantes dans l’utilisation de l’IAg utilisaient principalement cette technologie pour des tâches fonctionnelles telles que l’organisation d’informations ou la réalisation de recherches superficielles. Grâce à une approche expérientielle et à une réflexion guidée, les personnes étudiantes ont démontré une amélioration de leur confiance, de leur compréhension éthique et de leur évaluation critique des résultats générés par l’IA. Les conclusions de la personne enseignante ont convergé avec les points de vue des personnes étudiantes, soulignant la valeur d’une approche étayée et réfléchie pour le développement des compétences. L’intégration des résultats quantitatifs et qualitatifs a mis en évidence l’efficacité de l’AE dans un cours conçu par l’IAg.

Mots-clés : littératie en intelligence artificielle, éthique, théorie de l’apprentissage expérientiel, littératie numérique, intelligence artificielle générative

The pace at which generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) has unfolded in education has been unprecedented (Adiguzel et al., 2023; Pelletier et al., 2022). As such, its influence on the field of education is now being considered in relation to the learning sciences and subsequent implications for course design, assessment, and the methods instructors employ to support digital and AI literacy for postsecondary students (Atlas, 2023; Chan & Hu, 2023). The advent of GenAI has significantly reshaped various landscapes, including education. GenAI, which includes models such as GPT-4 and tools such as DALL-E, can create text, images, and other content based on input data (i.e., large language models), presenting new opportunities for enhancing learning experiences.

In postsecondary education, where fostering critical thinking, creativity, and deep engagement is crucial, integrating GenAI tools into pedagogical practices can be transformative and deeply cultivate these competencies. The UNESCO framework for AI in education served as a rich foundation for informing this study and how well these learning opportunities prepare postsecondary students for the digital age (Chan & Hu, 2023; Floridi & Cowls, 2021). For example, the framework emphasizes the importance of four tenets of AI literacy: (a) recognizing and understanding AI, (b) using AI effectively, (c) critically assessing AI, and (d) ethical considerations of AI to be of primary focus in postsecondary teaching and learning environments (Castro et al., 2024). In this way, the UNESCO framework provided not only a conceptual backdrop but also a policy-aligned lens through which to examine how postsecondary education can cultivate informed, responsible, and reflective AI users.

This study explored the integration of GenAI in postsecondary education through the lens of experiential learning theory (ELT) to develop digital and AI literacies. In this postsecondary classroom context, learning was inquiry-based and in many ways experiential due to the nature of GenAI and digital technologies (Doolittle et al., 2023). Despite the rapid adoption of GenAI in higher education, there is a dearth of information in the literature and research on how GenAI-specific courses can support domain-specific learning and AI literacy development in an authentic way. Therefore, the objective of this study was to examine how ELT can support the development of digital and AI literacies in postsecondary education through the integration of GenAI tools. This mixed-methods study provides a unique contribution with the integration of ELT with GenAI literacy. The nuanced look at students’ literacy development contributes to an emerging area in this field.

To achieve this, the study leveraged ELT to understand how GenAI can be used to facilitate each stage of the learning cycle, including how students interact with GenAI case simulations, how students analyze and reflect on their interactions with GenAI, the theoretical insights students develop during their learning and reflection, and how students can apply their new knowledge in practical scenarios facilitated by AI tools. Understanding effective GenAI integration is vital for educators, policymakers, and AI developers, as it strengthens teaching practices, guides policy development, and enhances students’ digital and AI literacies.

The course under study was a bachelor-level elective offered within a Canadian postsecondary institution focused on digital and AI literacy through the lens of innovation and entrepreneurship. The course was intentionally designed to integrate experiential learning processes with the use of GenAI tools, enabling students to engage directly with technologies, shaping professional and academic contexts. The overarching objectives of the course were to (a) build foundational knowledge of AI and its ethical implications, (b) develop digital and AI literacies through applied learning tasks, and (c) cultivate critical reflection, creativity, and problem-solving using GenAI in real-world scenarios.

Enrollment was open to students from undergraduate, graduate, and doctoral levels across multiple disciplines, including business, communication, education, computer science, and the social sciences. This interdisciplinary structure was deliberate, aligning with the university’s emphasis on transdisciplinary learning and collaboration. The pedagogical design emphasized cross-disciplinary interaction, encouraging students to apply GenAI tools to authentic problems relevant to their own academic or professional domains.

Specifically, in this university context, a course was immersive to ensure course content was geared toward learning about GenAI tools and platforms, prompt engineering, and no-code coding nested in a business and innovation context. In the course, students had in-person and asynchronous learning through instructor-led exploration and an online discovery forum housed in the D2L (https://www.d2l.com/) shell. The weekly classes focused on prompt generation, no-code coding, image content creation, and investigating other GenAI tools used in industry and by entrepreneurs in various sectors, including fintech, medicine, and education services.

Additionally, weekly guest lecturers from education and industry extended the real-world context of AI and GenAI use. The course sequence started with a focus on learning the essentials of AI and using AI effectively, and then moved strategically to critically assessing AI and its ethical implications. Within this intentional flow, students had the opportunity to learn and practice prompt engineering with various large language models (LLMs), work through case-based studies of recent adoption cases, and fold in contextual facets of the guest lecturers’ lived experiences.

Students had multiple opportunities to explore, engage in structured play, and bring back their ideas and feedback to each class or engage on the discovery forum, where class members, teacher assistants, and the instructor posted probative questions and real-time content updates. This discovery forum provided a space for everyone despite the range of familiarity with GenAI, coding, and the content touchpoints for the course that were directly related to the assessments and learning tasks to share and interact with each other in the spirit of discovery. For the final assessments, students completed a prompt validation exercise, curation of contributions and sharing within the discovery board, and a summative transdisciplinary project whereby a group of four students from different academic levels and disciplines explored a complex problem within their community that could be solved using some form of AI.

From an experiential learning lens, the authenticity of learning was heightened as students could learn in a way that helped them experience facets of the real-world approach and, in this case, digital and AI tools being used in industry (Lu et al., 2021; Matook et al., 2021). ELT provided the theoretical lens for this study, offering a framework to understand how students develop digital and AI literacies through stages of concrete experience, reflection, conceptualisation, and experimentation (Kolb, 1984; Kolb & Kolb, 2017).

GenAI has been increasingly recognized for its potential to transform educational practices. Artificial intelligence tools can provide personalized learning experiences, create dynamic educational content, and facilitate interactive learning environments (Holmes et al., 2019). Studies have shown that AI can support differentiated instruction, catering to individual student needs and learning paces (Kim & Adlof, 2024; Zawacki-Richter et al., 2019). Furthermore, AI-generated simulations and scenarios can offer immersive learning experiences, and enhance student engagement and understanding (Lu et al., 2018; Rasul et al., 2023).

GenAI can precipitate the creation of tailored educational content by adapting to individual student learning approaches, cadence, and engagement points (Qureshi, 2023). For example, in this course, the tasks afforded students the opportunity to take personalized approaches to prompt engineering and validation as well as targeted explanations to problem sets distinct to a student’s interest areas (Thompson et al., 2023). Additionally, students who did not speak English as their primary language could use real-time language translations and attain simplified versions of complex materials in order to build their understanding in varied ways (Slimi, 2023). In this diverse postsecondary classroom setting, GenAI content, tools, and integration processes supported diverse learners at multiple stages of technological understanding (Turner et al., 2024).

From a competency or skill-based learning lens, learning about GenAI platforms and tools helped mitigate the digital divide and provide students with equitable access to tools and functions from a base (i.e., free) standing (Kim & Adlof, 2024). As Weng et al. (2024) asserted, it is unrealistic to expect students to comprehend all aspects of AI literacy on their own; providing authentic and real-world contexts to which students can learn and apply their understanding is essential. As such, a curriculum dedicated to AI integration and literacy created intentional learning environments prioritizing the necessary learning and skills development to help postsecondary students navigate the rapid evolution of technology.

In the context of postsecondary education and learning, providing a course specific to GenAI created the conditions to discuss levels of AI literacy including creating transparency around the notion of the black box, creating student capacity related to algorithmic bias, positive skepticism and fact-checking of these tools’ outputs, and the implications of attribution when using tools to write, edit, and ideate (Khlaif et al., 2024).

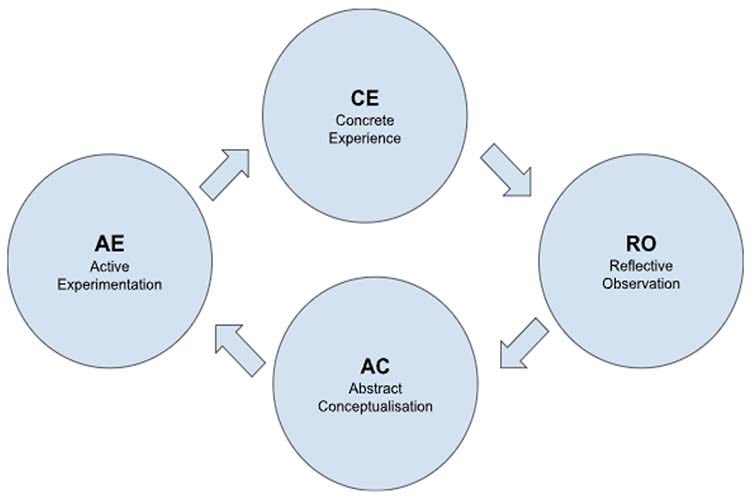

The ELT framework underpins this study (Kolb, 1984). ELT posits that learning is a process whereby knowledge is created in the transformation of experience (Kolb & Kolb, 2017). According to Kolb (1984), the stage of concrete experience in ELT involves direct, hands-on engagement in tasks within authentic learning environments. This phase allows learners to immerse themselves fully in practical activities, thereby facilitating a deeper understanding of real-world contexts and challenges. Reflective observation follows, requiring learners to systematically analyse and evaluate their experiences. During this phase, learners identify patterns, recognize underlying issues, and draw meaningful insights by critically examining both successes and failures. This reflective process is essential for bridging the gap between experience and learning. In the abstract conceptualisation stage, learners integrate newly acquired theoretical knowledge from academic coursework with their practical experiences.

This synthesis enables learners to formulate broader concepts, frameworks, and models that enhance their understanding of complex professional scenarios. By abstracting their experiences into generalized theories, students can develop a more sophisticated grasp of the principles underpinning their field. Finally, the active experimentation phase involves applying these conceptual understandings by testing the derived theories in real-world settings. This stage encourages learners to implement strategies, pilot innovative solutions, and refine their approaches based on empirical feedback. Through this iterative process of experimentation, learners not only validate theoretical models but also develop adaptive problem-solving skills that are critical for professional competence and lifelong learning.

This adapted cycle, shown in Figure 1, posits that learners gain knowledge through experiences, reflecting on these experiences, conceptualising the reflections into abstract ideas, and experimenting with these concepts in new situations. ELT has been widely adopted in various educational contexts, demonstrating its effectiveness in promoting deeper understanding and practical skills (Healey & Jenkins, 2000).

Figure 1

Experiential Learning Cycle

Note. Adapted from Kolb’s Experiential Learning Model (1984) for this study.

GenAI has been increasingly recognized for its potential to transform educational practices. Studies have shown that AI can support differentiated instruction, catering to individual student needs and learning paces through dynamic educational content and interactive learning environments (Holmes et al., 2019; Kim & Adlof, 2024; Thompson et al., 2023; Zawacki-Richter et al., 2019). Furthermore, AI-generated simulations and scenarios can offer immersive learning experiences, and enhance student engagement and understanding (Lu et al., 2018; Rasul et al., 2023).

Therefore, integrating GenAI with ELT presents a promising approach to enhancing learning outcomes and focusing on learning as a process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience. For example, whether structured or unstructured, play with GenAI can facilitate each stage of the ELT cycle, providing concrete experiences through simulations, aiding reflective observation with data analytics and feedback, supporting abstract conceptualisation by generating insights and patterns, and enabling active experimentation through interactive and adaptive learning environments. Research indicates that such integration can improve student engagement, creativity, and critical thinking (Luckin et al., 2016). GenAI can simulate environments, provide feedback, and generate diverse content that can offer transformative possibilities for enhancing ELT (Kim & Adlof, 2024).

Despite potential benefits, using GenAI in education raises challenges and ethical concerns such as data privacy, algorithmic bias, and the digital divide. In classroom settings, these should be addressed to ensure equitable and ethical use of AI (Kim & Adlof, 2024; Williamson & Eynon, 2020). Additionally, there is a risk of cognitive overload if students are overwhelmed by the volume and complexity of AI-generated information (Campello de Souza et al., 2024). These challenges necessitate a careful and balanced approach to integrating AI in educational settings (Campello de Souza et al., 2024).

Xia et al. (2024) reinforced that the rapid evolution of GenAI is posing unique ethical dilemmas within postsecondary education; in addition to implications of copyright violation, students’ ethical behaviour in academic settings when not properly supported to develop their digital literacy skills can be problematic. Many postsecondary environments lack appropriate policies and conduct codes to ensure students and instructors understand how best to implement GenAI and other tools (Sporrong et al., 2024). From an instructor perspective, the challenge of not being able to ascertain a student’s skills and knowledge raises concerns about whether they have used GenAI to complete assignments without attributing it in their work (Lyanda et al., 2024).

To reiterate, equitable access is a further challenge linked to the digital divide that needs to be underscored, given the diverse student populations of postsecondary learning environments. Monetary affordability and access (i.e., equity and accessibility) need to be considered when these tools or platforms are implemented to support student learning (Anuyahong et al., 2023; Bekdemir, 2024). Furthermore, having an awareness of who owns the copyright of student inputs as well as how best to support students in navigating the inherent bias in LLMs necessitates higher degrees of digital and AI literacy for both students and instructors (Lacey & Smith, 2023).

From an instructor practical perspective, fair grading principles are important when using AI grading systems, as the same bias could result in skewed marking or further ethical dilemmas in assessment design and evaluation (Dimari et al., 2024). Validity and reliability in assessment design and implementation are key metrics to support fair practices in postsecondary education, with policies highlighting these important facets (Khlaif et al., 2024). Overall, there is a consistent message across much of the literature regarding the importance of providing professional development and learning opportunities for faculty and instructors to understand how best to integrate GenAI into assessment practices and policy that reflects the understanding of postsecondary higher administration to guide the pedagogical and contextual facets of GenAI (Slotnick & Boeing, 2025).

This study employed an explanatory sequential mixed-methods design (Creswell & Creswell, 2018), integrating quantitative and qualitative data to provide a comprehensive understanding of students’ learning experiences with GenAI. In the first phase, quantitative data were collected through a structured survey designed to measure student engagement, critical thinking, and self-perceived gains in digital and AI literacies. These results informed the development of the qualitative phase, where semi-structured interviews explored the patterns and tensions that emerged from the survey data. The sequential design enabled the use of quantitative findings as a foundation for qualitative inquiry, thereby deepening interpretation and validating emerging insights.

Participants were recruited through purposeful sampling, reflecting voluntary course enrollment and a shared interest in learning with GenAI. This approach was appropriate given the exploratory, mixed-methods design and the study’s focus on capturing a range of perspectives across degree levels and specializations (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). Such diversity of experience enabled deeper analysis of how learners with different disciplinary and technological backgrounds developed digital and AI literacies through experiential engagement. Participants included students from undergraduate, graduate, and doctoral levels from various disciplines in the postsecondary institution. Participants were provided with clear information regarding the study’s purpose and data use. This study received approval from the institutional research ethics board of the participating university. Participants were assured that their data would be kept confidential and that their participation was voluntary, with the right to withdraw at any time without penalty.

Several participants were involved in both the quantitative and qualitative phases, as several students who completed the survey also volunteered for follow-up interviews. This overlap facilitated triangulation of findings and enhanced the credibility of the interpretations (Ponce & Pagán-Maldonado, 2015). The mixed-methods approach was selected to illuminate both the measurable outcomes of GenAI integration, such as engagement and literacy development, and the nuanced, experiential processes by which students constructed meaning from their interactions with AI tools. This methodological combination was well-suited to the study’s exploratory purpose and its theoretical grounding in ELT, which emphasized the iterative interaction between experience, reflection, and conceptual understanding.

The methods included a survey (N = 17) that was completed by the course instructor and student participants, designed to integrate GenAI into the entrepreneur and innovation content and immerse students in the experiences of learning with GenAI in this domain. Then, interviews (N = 16) were completed, and qualitative data were collected from students and the instructor about their experiences and perspectives related to the study’s purpose and objectives. The combination of these methods allowed for a robust examination of the efficacy of GenAI in enhancing experiential learning.

ELT served as the conceptual framework guiding both the design of the survey instruments and the analysis of qualitative data. The survey items were intentionally mapped to Kolb’s (1984) four stages of experiential learning—concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation, and active experimentation—to capture how students engaged with GenAI across these dimensions. For instance, items related to concrete experience assessed students’ hands-on use of AI tools, while items aligned with reflective observation explored how students critically evaluated the accuracy and ethics of AI-generated content. Items associated with abstract conceptualisation measured students’ ability to connect their experiences to theoretical or disciplinary knowledge, and active experimentation items examined how students applied new understandings of GenAI to real-world or project-based contexts.

Similarly, ELT informed the qualitative coding and thematic analysis of interview data. Student reflections and interview transcripts were coded deductively based on ELT’s cyclical model, with inductive subcodes emerging within each stage to represent unique experiences (Braun & Clarke, 2022). This dual approach ensured theoretical alignment while allowing for emergent themes specific to learning with GenAI. By embedding ELT into both data collection and analysis, the study maintained conceptual coherence and provided a structured lens through which to interpret students’ digital and AI literacy development.

The survey instrument was designed to examine how students experienced GenAI enhanced learning within the four stages of ELT. The survey comprised 21 items organized into three thematic areas: (a) student engagement and experiential learning, (b) digital and AI literacy development, and (c) ethical awareness and reflective practice. Items were constructed using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree and were reviewed by two experts in educational technology and assessment to ensure content validity and alignment with ELT constructs.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize response distributions given the exploratory purpose and small sample size (Braun & Clarke, 2022). While all 21 items were analyzed, Table 2 presents the 6 most illustrative items that directly map onto ELT stages, offering a concise view of how students perceived their experiential learning progression within a GenAI context. The internal consistency of the overall instrument, assessed via Cronbach’s alpha (.86), indicated acceptable reliability for an exploratory study. These data provided a quantitative foundation for the subsequent qualitative analysis, allowing patterns of engagement, reflection, and literacy development to be compared and contextualized across methods.

As the class was interdisciplinary and multi-leveled, Table 1 includes the participant demographics to help contextualize the reality in this course.

Table 1

Interdisciplinary and Multi-Leveled Student Demographic Information

| Participant | Degree level | Area of specialization |

| 1 | Bachelor | Communications |

| 2 | Bachelor | Business and Commerce |

| 3 | Bachelor | Computer Science |

| 4 | Bachelor | Nursing |

| 5 | Bachelor | Social Work |

| 6 | Bachelor | Marketing |

| 7 | Bachelor | Computer Science |

| 8 | Bachelor | Nursing |

| 9 | Bachelor | Marketing |

| 10 | Master | Arts |

| 11 | Master | Business Administration |

| 12 | Master | Communications |

| 13 | Master | Adult Education |

| 14 | PhD | Indigenous Studies Focus |

| 15 | PhD | Women’s Studies |

| 16 | PhD | Business |

| 17 | PhD | Business |

The initial baseline results presented in Table 2 revealed that most students entered the course at a GenAI use beginner level, characterized by low technical proficiency and limited critical awareness. Their engagement with AI tools prior to instruction was largely utilitarian, focused on everyday tasks such as organizing information, generating recipes, or conducting surface-level research. These findings suggest that initial encounters with GenAI were pragmatic rather than pedagogical, emphasizing convenience and curiosity over intentional learning. The low frequency of use and limited understanding of prompt design or ethical implications further underscored their novice status. In line with ELT, this baseline highlights the importance of providing structured opportunities for concrete experience and guided reflection, allowing students to transition from functional to conceptual and ethical forms of AI literacy. By establishing this initial point of reference, the study was able to trace how experiential engagement throughout the course supported the development of deeper critical and reflective capacities in students’ digital and AI literacies.

Against this backdrop, and as shared in the instructors’ qualitative survey responses, keeping up with the constant changes in the field proved challenging. As such, a concerted effort was made to cultivate a culture of deep learning and to shift the instructor’s role from expert to facilitator, to co-learner. This was powerful for postsecondary students to understand the importance of equipping them with the necessary digital and AI literacies through experiential learning. The quantitative results reflect student perceptions and experiences within the course and the connections to the experiential learning frame.

Table 2

Students’ Baseline Experiences With GenAI

| Aspect of GenAI use | Illustrative student behaviours/examples | Frequency, % | Interpretation |

| Self-assessed proficiency | Most students described themselves as beginners in using GenAI (e.g., “I only used ChatGPT occasionally for small tasks”). | 88 (beginner) 12 (intermediate) | Indicates limited prior exposure to AI tools. |

| Primary purposes for use | Searching for recipes, organizing schedules or notes, light research assistance, summarizing online content. | 76 | Suggests pragmatic and surface-level engagement. |

| Technical skill awareness | Limited understanding of prompt engineering or model functionality; uncertainty about “how AI works.” | 70 | Reflects a need for structured scaffolding and conceptual grounding. |

| Ethical and critical awareness | Minimal prior reflection on bias, intellectual property, or citation of AI-generated outputs. | 64 | Reveals early-stage critical literacy development. |

| Frequency of use prior to course | Occasional to rare (e.g., 1–2 times per month); mostly curiosity-driven or exploratory. | 82 | Confirms baseline novice familiarity and infrequent use. |

Note. N = 17. GenAI = generative artificial intelligence.

The data in Table 3 illustrate strong alignment between students’ learning experiences and the core dimensions of ELT—concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation, and active experimentation (Kolb, 1984). Across all indicators, student responses were overwhelmingly positive, demonstrating that the course design effectively supported iterative cycles of experience, reflection, conceptualisation, and application in relation to GenAI.

A significant majority of students (81.25%) strongly agreed that the course deepened their understanding of the utility of GenAI, with an additional 6.25% somewhat agreeing. This suggests that instructional design elements successfully facilitated conceptual synthesis, helping students move beyond tool familiarity toward articulating more abstract understandings of GenAI’s pedagogical and practical value. The absence of disagreement indicates strong conceptual engagement across the cohort.

Similarly, 81.25% of respondents strongly agreed that learning tasks shaped how they applied critical thinking in their understanding of GenAI. This reflects the “doing” and “feeling” phases of experiential learning, where direct engagement with authentic, technology-rich tasks enabled students to construct personal meaning. Only a minimal proportion (6.25%) reported slight disagreement, reinforcing that experiential immersion fostered cognitive engagement and self-directed inquiry. The students also reaffirmed that their learning resulted in increased critical thinking due to the prompt-engineering opportunities, using the AI tools to develop visual content, and the transdisciplinary approach to their final project, which was linked to human-centred design and finding solutions to their community’s wicked problems (Schön, 1992). Overall, 93.75% (81.25% strongly agreeing and 12.5% somewhat agreeing) of student participants asserted that the learning scenarios they encountered enhanced their critical thinking and problem-solving abilities. However, it can be speculated that a few students (6.25%) did not believe their critical thought was advanced due to their surface level engagement with prompt engineering or the lack of engagement they may have felt in the prompt-validation assignment, peer engagement in the discovery board, and the final transdisciplinary project.

Table 3

Frequency of Student Survey Responses Linked to the Experiential Learning Theory

| Student response | Strongly agree, % | Somewhat agree, % | Neither agree nor disagree, % | Somewhat disagree, % | Strongly disagree, % |

| The way the course was designed, and my learning experiences deepened my understanding of the utility of GenAI (i.e., abstract conceptualisation). | 81.25 | 6.25 | 12.50 | - | - |

| The course and learning tasks helped shape how I applied critical thinking in my understanding of GenAI (i.e., concrete experience). | 81.25 | 12.50 | - | 6.25 | - |

| The online discovery forum helped me steer my learning in the course (i.e., active experimentation). | 50.00 | 43.75 | 6.25 | - | - |

| The tools and platforms used in the course enhanced my experiences of learning and reflection on my learning (i.e., reflective observation). | 75.00 | 25.00 | - | - | |

| Prompting skills make a difference in how a person uses GenAI (i.e., active experimentation and reflective observation) | 81.25 | 18.75 | - | - | - |

| The learning experiences in this course have positively influenced my interest in pursuing further knowledge and skills related to GenAI (i.e., active experimentation and reflective observation). | 80.00 | 13.33 | 6.67 | - | - |

Note. The dash (-) denotes a value of zero.

Given this finding, Anuyahong et al. (2023) asserted that not all use of GenAI results in critical thinking, particularly when learners do not understand how to constrain prompts and provide context for the LLM to refine its output. This perspective helps explain why a small proportion of students may not have perceived an increase in critical thinking. In contrast, many students demonstrated deeper engagement through tasks that required intentional planning, contextual reasoning, and iterative refinement. For instance, students used image-generator tools to create branding materials for a fictitious company, which involved applying branding principles and constructing prompts to generate image-based content with the GenAI tools. Additionally, students used the project deliverable as an opportunity to create authentic solutions using GenAI in areas such as increasing children’s literacy with book creation tools, supporting wellness with a nutrition bot, and gamifying learning for middle school students in STEM courses. These tasks provided rich opportunities for experiential learning and reinforced the development of critical thinking and problem-solving skills.

Reflection emerged as a critical mediating process with 75% of participants strongly agreeing that the tools and platforms enhanced their reflection on learning, while the remaining 25% somewhat agreed. This uniform positivity underscores the intentional design of digital environments that support metacognitive awareness, encouraging students to evaluate both their learning processes and outcomes. Reflection also appeared integral in linking prompting skills to effective AI use, as evidenced by 100% agreement that prompting skills make a difference, bridging reflection and experimentation.

Students’ engagement in active experimentation was evident in their perceptions of both the online discovery forum and their sustained interest in AI learning. Half of the cohort (50%) strongly agreed and 43.75% somewhat agreed that the discovery forum allowed them to steer their learning, demonstrating high levels of learner agency and iterative idea testing. Moreover, 93.33% of respondents agreed that their experiences enhanced their interest in further learning, highlighting the cyclical continuity of ELT wherein experimentation generates motivation for deeper future inquiry.

Results also reflected the challenges or constraints of learning with GenAI, such as the technical awareness of learning the tools and the essence of prompt engineering (Delanoy & Keyhani, 2025). Additionally, ethical concerns related to bias and the implications of the data that LLMs are trained on, as well as the creation of content and intellectual property presented further challenges. For example, students shared that once they understood the inner workings of LLMs, they were more critical of the outputs and developed an increased awareness of the models used for the training. Further, students shared that when they were beginners in using GenAI, they could recognize the dilemma of becoming over-reliant on the tool without first considering the task and its expectations, and then using GenAI to verify their decisions during exploration, problem-solving, or analysis.

Regarding the reception of experiential learning to the main themes, students said they experienced a more profound level of learning. This was evident as they transitioned from acquiring knowledge to transferring and applying what they learnt (Doolittle et al., 2023), effectively using the course content in practical situations. The constancy of iterative thinking was a fulsome theme for most students. Despite being provided with baseline settings and a website containing prompts from individuals worldwide, participants still had to carefully analyse their objectives and choose which linguistic sequences (i.e., limitations) would provide the most favourable outcomes.

Findings from the instructor survey closely paralleled those of the students, suggesting strong alignment in perceptions of GenAI as a catalyst for engagement and critical inquiry. The instructor reported that GenAI supported active learning and critical thinking while requiring careful facilitation to address ethical and evaluative challenges. Like the students, the instructor expressed both optimism and caution, highlighting opportunities for authentic problem-solving and efficiency, alongside concerns about overreliance and accuracy of AI outputs. This convergence reinforces the experiential nature of the learning environment, where both instructors and students engaged in iterative cycles of exploration, reflection, and conceptual understanding consistent with the stages of ELT.

The student quotations presented in Table 4 were selected as representative exemplars of the major qualitative themes identified through the coding process. Each quote reflects a central idea that appeared across multiple participants and was chosen to illustrate both thematic depth and diversity of perspective. Approximately 6 of the 16 interview participants shared experiences consistent with each of these key themes, particularly around critical thinking, ethical reflection, and applied experimentation with GenAI. The inclusion of these excerpts ensures that student voices are foregrounded while maintaining coherence with the broader quantitative findings and theoretical alignment with ELT.

In the context of ELT from tables 3 and 4, postsecondary students were able to hone specific skills and competencies that were explicit in the course design such as prompt engineering or image creation; however, what was implicit was how the student quotes reflected the tacit development of cognitive ability and soft skills including communication, empathy, sharing, metacognition, and being inspired to continue their learning journey (Weng et al., 2024). While some competencies may not be directly linked to the use of GenAI, the use of experiential learning, which is learning by doing in both an individual and group context, needs to be underscored (Kolb & Kolb, 2017). Secondary benefits were apparent as students had to help each other to work with technology that they may not have used in such depth before. The ambiguity caused by the rapid evolution of the technology during the course resulted in students becoming comfortable with change.

Table 4

Student Quotes—Interview Responses Linked to Experiential Learning Theory

| Experiential learning theory | Student quote |

| Critical contemplation | “I found myself constantly reflecting because of the ways this new technology works. I approached the learning tasks for prompt engineering and the final project in very critical ways and as an MBA student enrolled in the course, I needed to consider what I wanted out of my prompt designs and how best to work within a team with people of varying abilities in applying AI.” (Student 5) |

| Collaboration and sharing | “Regardless of my technical skills going into the course, I needed to be able to collaborate in groups for certain tasks as we used AI tools and connect and share with others on the discovery board; I come from a computer science background and in this class level of sharing and working together based on the learning design helped me tremendously.” (Student 8) |

| Focusing on the process | “When I started the course, I only used generative AI to find recipes and now I can engineer high-quality prompts with effective outputs which transfer readily to using Midjourney to create images, and I am now confident enough to help others. Process-driven approaches such as prompt engineering helped me with my critical thinking and problem-solving skills even as an existing PhD student.” (Student 3) |

| Navigating uncertainty during a time of rapid change | “While I was taking this course, so much changed even from one week to another. The professor had to change course multiple times when new advancements happened with the tools we used. Living through this and watching the professor adapt quickly to change helped me be more comfortable within the changing field.” (Student 2) |

| Insights of others | “I was in a group of bachelor, MBA, and PhD students for my final project. At first, I was intimidated but we all were working for the same goals, and everyone helped each other learn regardless of the level they were at. I felt like I learned from others continuously and gained a better appreciation of the wisdom everyone brought to our project.” (Student 10) |

| Lifelong learning | “I considered myself very capable of using GenAI from my experiences in software development in my previous career. Yet, when I took this course, I found myself constantly learning and my critical thinking skills increased significantly. I internalized the ethical issues and dilemmas more deeply as a user and creator of content. Learning in this class influenced me to start taking Google micro-credentials to expand my learning as I consider going into law school. I am beyond curious about where else this learning can take me.” (Student 12) |

Furthermore, students who would have considered themselves beginner users learned more about the inner workings of GenAI and the ethical realities of algorithmic bias, stereotypical information, and the importance of attributing their work (Khlaif et al., 2024). Moreover, the students’ prompt-engineering methods yielded direct gains, and sharing within the class inculcated a culture of deeper thinking and curiosity, and positively made the process more important than the product (Kolb & Kolb, 2017). Using GenAI in postsecondary contexts can elevate student learning when the appropriate digital and AI literacies are taught, modeled, and embedded in learning tasks, class discussions, and the discovery forum. In the context of ELT in a postsecondary learning environment, where the focus is on developing digital and AI literacies, learning by doing can establish a rich foundation for student learning.

The integration of quantitative and qualitative findings revealed a consistent pattern demonstrating that students’ engagement with GenAI supported the iterative processes of learning described in ELT. The survey data indicated high levels of agreement across ELT-aligned items, particularly those relating to critical thinking, active experimentation, and reflective observation. These numerical trends were reinforced by the qualitative findings, in which students described concrete experiences of using GenAI to explore ideas, refine prompts, and evaluate AI-generated outputs. Together, these results suggest that experiential interaction with GenAI contributed to students’ emerging digital and AI literacies by situating learning within authentic, problem-based contexts.

Triangulation of both data strands also demonstrated convergence in student and instructor perceptions. Quantitatively, both groups emphasized the usefulness of GenAI for enhancing engagement and critical thinking, while qualitatively, they described a parallel process of reflection and adaptation that deepened conceptual understanding. Students who initially self-identified as beginners reported, through interviews, a growing confidence and ethical awareness by the end of the course findings mirrored by instructors’ observations of students’ increased independence and critical evaluation of AI tools. This convergence underscores the value of integrating experiential and reflective components in AI-focused learning design, reinforcing ELT’s proposition that meaningful learning emerges through the cyclical interplay of experience, reflection, conceptualisation, and experimentation.

Taken together, these integrated findings highlight how experiential learning with GenAI can simultaneously foster technical proficiency, critical awareness, and ethical judgment. The convergence of evidence across data sources reinforces the central role of reflective and applied learning in shaping students’ AI literacy trajectories. Building on these outcomes, the following discussion situates these results within broader conversations on assessment innovation, instructional design, and the evolving role of experiential pedagogy in digital and AI-enhanced learning environments.

Students’ engagement in experiential learning made a discernible difference in their development of both digital and AI literacies. Quantitative survey data indicated notable increases in self-reported confidence, ethical awareness, and the ability to critically evaluate GenAI outputs by the end of the course. Qualitative reflections reinforced these findings: students described progressing from functional use of AI tools for convenience tasks (e.g., organizing, searching, or summarizing information) toward more intentional and critical engagement. Through iterative cycles of exploration and reflection, learners began to recognize the affordances and limitations of GenAI, acknowledging its potential as both a creative collaborator and a subject of ethical scrutiny. These outcomes suggest that experiential engagement, learning through doing, reflecting, and refining, effectively scaffolded the transition from novice to more competent, reflective AI users.

Furthermore, students’ narratives revealed how concrete experience and reflective observation, two central stages of ELT (Kolb, 1984; Kolb & Kolb, 2017), were particularly influential in this growth. Working with real-world prompts and evaluating AI-generated outputs created authentic learning contexts that deepened conceptual understanding and digital discernment. Students reported increased awareness of issues such as data bias, authorship, and appropriate citation of AI-assisted work, reflecting higher-order literacy competencies. This shift illustrates how experiential learning fosters both technical fluency and ethical mindfulness, positioning AI literacy not merely as a set of operational skills but as a reflective and responsible practice. These findings underscore the pedagogical value of embedding GenAI experiences within structured cycles of experience, reflection, conceptualisation, and experimentation to cultivate sustainable and critical digital literacies.

The findings of this study reinforce that the integration of GenAI within an ELT framework can meaningfully advance students’ digital and AI literacies. This study was motivated by a notable gap in the literature: despite the rapid uptake of GenAI in postsecondary education, little is known about how GenAI-specific courses can authentically support domain-specific learning and the development of digital and AI literacies. To address this gap, the study aimed to examine how ELT can support the development of digital and AI literacies in postsecondary education through the integration of GenAI tools.

Students’ quantitative baseline data (Table 1) revealed limited prior exposure to GenAI tools, with most identifying as beginners who used AI primarily for simple, utilitarian tasks such as searching for recipes, organizing schedules, or summarizing information. This aligns with recent evidence that novice learners often engage with AI tools in pragmatic, low-stakes ways before formal instruction (Khlaif et al., 2024). Within the course, structured experiential opportunities helped students move from these functional applications toward conceptual and ethical engagement. Through guided practice, reflection, and iterative experimentation, learners began to perceive AI not merely as an assistive technology but as a cognitive partner that could extend creativity, reasoning, and self-regulation (Weng et al., 2024).

Quantitative results demonstrated strong alignment between students’ experiences and ELT’s cyclical stages. As shown in Table 2, the baseline experiences of students, more than 80% of students agreed that the course design deepened their understanding of GenAI’s utility and supported critical thinking and reflection. These findings echo Doolittle et al. (2023), who emphasized that active learning and reflective observation increase metacognitive awareness and transfer of learning. Qualitative data extended these insights: student quotations presented in Table 3 capture the development of higher-order competencies such as collaboration, critical contemplation, and lifelong learning. Students described their transformation from hesitant users to confident, reflective practitioners, an evolution that mirrors Kolb’s (1984) assertion that knowledge emerges through the transformation of experience and Kolb and Kolb’s (2017) argument that learning requires recursive cycles of doing, reflecting, thinking, and applying.

The convergence between student and instructor perceptions further validates the course’s experiential design. The instructor reported similar growth patterns, observing that students who engaged deeply with GenAI tasks demonstrated increased autonomy, ethical reasoning, and problem-solving capacity. Both groups highlighted the duality of GenAI as empowering yet demanding of discernment, a finding consistent with Anuyahong et al. (2023), who cautioned that AI use does not inherently promote critical thinking unless learners understand how to frame prompts and critically assess outputs. These aligned perspectives underscore the need for instructors to assume the role of facilitator and co-learner, adapting to rapid technological change while fostering student agency and reflective practice.

At a broader level, this study contributes to emerging conversations on AI literacy as an experiential and ethical construct. Students’ reflections suggest that effective AI literacy extends beyond technical fluency to include awareness of algorithmic bias, data transparency, and intellectual property. As Kolb and Kolb (2017) and Schön (1992) contended, authentic learning arises when learners confront uncertainty and apply reflection-in-action to complex problems. Likewise, the course’s design, emphasizing iterative experimentation and peer collaboration, cultivated comfort with ambiguity and adaptability, competencies essential for lifelong learning in rapidly evolving digital contexts (Qureshi, 2023).

Ultimately, the integration of GenAI within ELT’s experiential framework fostered measurable and perceptible growth in students’ digital and AI literacies. Learners progressed from basic tool use toward deeper ethical and conceptual understanding, demonstrating that learning by doing and reflecting remains a powerful pathway for cultivating critical digital competencies in higher education. These findings highlight that when experiential learning principles are intentionally embedded in AI-enhanced courses, GenAI can evolve from a technological novelty into a pedagogical catalyst for creativity, reflection, and innovation (Castro et al., 2024).

Given the study’s limitation of a smaller sample size of 33 participants (i.e., survey: N = 16 and interviews: N = 17), the results should be generalized with caution and may be representative of a certain population, that being students engaging in a postsecondary course focused on learning with GenAI within an experiential learning frame. Using a mixed-methods approach of both quantitative and qualitative data can mitigate the smaller sample size of student participants by also providing rich, deep, and contextual data to provide a greater understanding of the efficacy of GenAI in enhancing experiential learning. Regardless, the generalizability of the data should be attempted with caution.

This study provides empirical evidence of how GenAI, when intentionally embedded within an ELT framework, can enhance digital and AI literacies in postsecondary education. By linking Kolb and Kolb’s (2017) cyclical stages of experience, reflection, conceptualisation, and experimentation with GenAI-mediated learning, the study demonstrates a replicable model for cultivating both technical proficiency and ethical awareness. The findings highlight that structured opportunities for guided reflection, collaborative problem-solving, and iterative prompt-engineering help students transition from functional users of AI to reflective, critical, and ethically aware learners. This evidence contributes to the growing body of research positioning AI literacy not as a discrete skill but as an iterative, human-centred learning process that integrates cognition, critical thinking, creativity, and ethics (Doolittle et al., 2023; Weng et al., 2024).

For educators and researchers seeking to replicate or extend this work, several recommendations emerge. First, AI-enhanced courses should be intentionally designed to align each learning outcome with the stages of ELT, ensuring that learners engage in authentic, hands-on exploration and reflective synthesis. Second, mixed-methods designs, combining descriptive and thematic analyses, are recommended to capture both the measurable shifts in learner confidence and the nuanced transformations in ethical reasoning and critical engagement. Replication studies could employ pre- and post-assessment measures of AI literacy, triangulated with reflective journals and design artifacts, to deepen understanding of literacy progression over time. Establishing clearer frameworks for evaluating how students learn with AI, rather than merely what they produce, would further enhance methodological robustness and comparability across contexts.

Future research should also explore longitudinal impacts of experiential AI learning, including how sustained engagement influences students’ professional identity, ethical decision-making, and adaptability in rapidly evolving technological landscapes. Additionally, comparative studies across disciplines, such as education, business, and engineering, could reveal how GenAI integration interacts with disciplinary epistemologies and assessment practices. Investigating the instructor’s evolving role as co-learner and facilitator in AI-enhanced environments would further illuminate the pedagogical shifts required for ethical and sustainable AI adoption in higher education (Khlaif et al., 2024).

The broader significance of this study lies in its contribution to both theory and practice at a critical juncture for digital education. It underscores that AI-enhanced experiential learning has the potential to transform classrooms into spaces of ethical inquiry, creative experimentation, and human-centred innovation. By offering a transparent framework for course design and research replication, this work invites educators and policymakers to take informed action, integrating GenAI not as an efficiency tool but as a catalyst for deeper learning, reflection, and social responsibility in the AI era.

This study demonstrates that integrating ELT with the use of GenAI can effectively strengthen students’ digital and AI literacies in postsecondary education. Through the interplay of experience, reflection, conceptualisation, and experimentation, learners moved beyond basic tool use toward more reflective, ethical, and critical engagement with AI. The findings underscore that structured experiential approaches, where students actively use, critique, and adapt GenAI tools, create authentic opportunities for developing both technical competence and ethical judgment. This synthesis of theory and practice offers a replicable model for educators seeking to embed AI literacy development within experiential and inquiry-based pedagogies. This mixed-methods study offers a distinctive contribution by integrating ELT with the development of GenAI literacy, providing a nuanced examination of how students cultivate AI-related competencies through experiential engagement.

For instructors and researchers aiming to replicate or extend this work, several key considerations emerge. Designing AI-enhanced courses should begin with explicit alignment between learning outcomes and ELT stages, ensuring opportunities for both concrete engagement with AI and guided reflection on its implications. Researchers are encouraged to adopt mixed methods designs to capture the nuanced relationship between students’ experiential processes and their evolving literacies, while also including instructor perspectives to triangulate learning impact. The criticality and measured skepticism should be built into the learning sequences, whether in classes dedicated to an AI curriculum or whether the courses integrate AI literacy as a part of the learning in the domain.

Future research could examine longitudinal impacts of experiential AI learning on students’ sustained literacy practices and professional readiness or explore discipline-specific adaptations of ELT frameworks for GenAI integration in fields such as teacher education, business, or engineering. Investigating how experiential engagement influences well-being, cognitive load, or ethical reasoning over time would also extend current findings and inform instructional design.

Overall, this study contributes to the growing body of research at the intersection of experiential pedagogy and AI literacy, demonstrating how GenAI can serve not only as a technological tool but as a catalyst for reflective, human-centred learning. By situating AI use within structured experiential cycles, educators can cultivate critical, ethical, and adaptive learners prepared to navigate rapidly evolving digital environments, thereby advancing both the scholarship and the practice of teaching and learning in the age of AI.

By positioning AI literacy as both a cognitive and experiential pursuit, this study illustrates how thoughtfully designed, theory-informed learning environments can transform GenAI from a technological novelty into a pedagogical catalyst for innovation, reflection, and ethical practice in postsecondary education. As AI continues to advance, postsecondary faculty and instructors with the lens of preparing students for the world beyond the degree need to consider their roles in not only fostering learning within the specialization in which they teach and research but also consider how AI can be an equalizer for students when framed within an ELT approach. As the state of knowledge building and transference evolves, so too does the need to use teaching and learning methods that are innovative and serve to provide value for postsecondary students and institutions as preparatory places for the world of work and to develop responsible, ethical citizens.

Adiguzel, T., Kaya, M. H., & Cansu, F. K. (2023). Revolutionizing education with AI: Exploring the transformative potential of ChatGPT. Contemporary Educational Technology, 15(3), Article ep429. https://doi.org/10.30935/cedtech/13152

Anuyahong, B., Rattanapong, C., & Patcha, I. (2023). Analyzing the impact of artificial intelligence in personalized learning and adaptive assessment in higher education. International Journal of Research and Scientific Innovation (IJRSI), X(IV), 88-93. https://doi.org/10.51244/ijrsi.2023.10412

Atlas, S. (2023). ChatGPT for higher education and professional development: A guide to conversational AI. DigitalCommons@URI. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/cba_facpubs/548

Bekdemir, Y. (2024). The urgency of AI integration in teacher training: Shaping the future of education. Journal of Research in Didactical Sciences, 3(1), 37-41. https://doi.org/10.51853/jorids/15485

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic analysis: A practical guide (1st ed.). SAGE Publications.

Campello de Souza, B., Serrano de Andrade Neto, A., & Roazzi, A. (2024). The generative AI revolution, cognitive mediation networks theory and the emergence of a new mode of mental functioning: Introducing the Sophotechnic Mediation scale. Computers in Human Behavior: Artificial Humans, 2(1), Article 100042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbah.2024.100042

Castro, R. A. G., Cachicatari, N. A. M., Aste, W. M. B., & Medina, M. P. L. (2024). Exploration of ChatGPT in basic education: Advantages, disadvantages, and its impact on school tasks. Contemporary Educational Technology, 16(3). https://doi.org/10.30935/cedtech/14615

Chan, C. K. Y., & Hu, W. (2023). Students’ voices on generative AI: Perceptions, benefits, and challenges in higher education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20(43). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00411-8

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). SAGE Publications.

Delanoy, N., & Keyhani, M. (2025). Fostering AI literacy: Implementing IBL and experiential learning in a novel generative AI course in higher education. In Archer-Kuhn, B., MacKinnon, S. & Beltrano, N. (Eds.), Applying inquiry-based learning in higher education across disciplines (1st ed.). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Dimari, A., Tyagi, N., Davanageri, M., Kukreti, R., Yadav, R., & Dimari, H. (2024). AI-based automated grading systems for open book examination system: Implications for assessment in higher education. In 2024 International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Communication Systems (ICKECS; pp. 1-7). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICKECS61492.2024.10616490

Doolittle, P., Wojdak, K., & Walters, A. (2023). Defining active learning: A restricted systematic review. Teaching & Learning Inquiry, 11, 1-23. https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.11.25

Floridi, L., & Cowls, J. (2021). A unified framework of five principles for AI in society. In L. Floridi (Ed.). Ethics, governance, and policies in artificial intelligence. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81907-1_2

Healey, M., & Jenkins, A. (2000). Kolb’s experiential learning theory and its application in geography in higher education. Journal of Geography, 99(5), 185-195. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00221340008978967

Holmes, W., Bialik, M., & Fadel, C. (2019). Artificial intelligence in education: Promises and implications for teaching and learning. Center for Curriculum Redesign.

Khlaif, Z. N., Ayyoub, A., Hamamra, B., Bensalem, E., Mitwally, M. A. A., Ayyoub, A., Hattab, M. K., & Shadid, F. (2024). University teachers’ views on the adoption and integration of generative AI tools for student assessment in higher education. Education Sciences, 14(10), Article 1090. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14101090

Kim, M., & Adlof, L. (2024). Adapting to the future: ChatGPT as a means for supporting constructivist learning environments. TechTrends: Linking Research & Practice to Improve Learning, 68(1), 37-46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-023-00899-x

Kolb, A. Y., & Kolb, D. A. (2017). Experiential learning theory as a guide for experiential educators in higher education. Experiential Learning & Teaching in Higher Education, 1(1), Article 7. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/elthe/vol1/iss1/7

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice Hall.

Lacey, M. M., & Smith, D. P. (2023). Teaching and assessment of the future today: Higher education and AI. Microbiology Australia, 44(3), 124-126. https://doi.org/10.1071/MA23036

Lu, K., Pang, F., & Shadiev, R. (2021). Understanding the mediating effect of learning approach between learning factors and higher order thinking skills in collaborative inquiry-based learning. Educational Technology Research & Development, 69(5), 2475-2492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-021-10025-4

Lu, O. H. T., Huang, A. Y. Q., Huang, J. C. H., Lin, A. J. Q., Ogata, H., & Yang, S. J. H. (2018). Applying learning analytics for the early prediction of students’ academic performance in blended learning. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 21(2), 220-232. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26388400

Luckin, R., Holmes, W., Griffiths, M., & Forcier, L. B. (2016). Intelligence unleashed: An argument for AI in education. Pearson.

Lyanda, J. N., Owidi, S. O., & Simiyu, A. M. (2024). Rethinking higher education teaching and assessment in-line with AI innovations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. African Journal of Empirical Research, 5(3), 325-335. https://doi.org/10.51867/ajernet.5.3.30

Matook, S., Wang, Y. M., Koeppel, N., & Guerin, S. (2021). Experiential learning in work-integrated learning (WIL) projects for metacognition: Integrating theory with practice. In ACIS 2021 Proceedings, Article 77. https://aisel.aisnet.org/acis2021/77

Pelletier, K., McCormack, M., Reeves, J., Robert, J., Arbino, N., Al-Freih, M., Dickson-Deane, C., Guevara, C., Koster, L., Sánchez-Mendiola, M., Bessette, L. S., & Stine, J. (2022). 2022 EDUCAUSE horizon report: Teaching and learning edition. EDUCAUSE. https://library.educause.edu/-/media/files/library/2022/4/2022hrteachinglearning.pdf

Ponce, O. A., & Pagán-Maldonado, N. (2015). Mixed Methods Research in Education: Capturing the Complexity of the Profession. International Journal of Educational Excellence, 1(1), 111-135. https://doi.org/10.18562/IJEE.2015.0005

Qureshi, B. (2023). ChatGPT in computer science curriculum assessment: An analysis of its successes and shortcomings. In M. D. Ventura & H. Yu (Chairs), ICSLT ‘23: Proceedings of the 2023 9th International Conference on E-Society, E-Learning and E-Technologies (pp. 7-13). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3613944.3613946

Rasul, T., Nair, S., Kalendra, D., Robin, M., de Oliveira Santini, F., Ladeira, W., Sun, M., Day, I., Rather, R. A., & Heathcote, L. (2023). The role of ChatGPT in higher education: Benefits, challenges, and future research directions. Journal of Applied Learning and Teaching, 6(1), 41-56. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.T2025102700000390990155131

Schön, D. A. (1992). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action (pp. 21-49). Taylor & Francis Group.

Slimi, Z. (2023). The impact of artificial intelligence on higher education: An empirical study. European Journal of Educational Sciences, 10(1), 17-33. https://doi.org/10.19044/ejes.v10no1a17

Slotnick, R. C., & Boeing, J. Z. (2025). Enhancing qualitative research in higher education assessment through generative AI integration: A path toward meaningful insights and a cautionary tale. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2025(182), 97-112. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.20631

Sporrong, E., McGrath, C., & Cerratto Pargman, T. (2024). Situating AI in assessment—An exploration of university teachers’ valuing practices. AI and Ethics, 5, 2381-2394. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-024-00558-8

Turner, L., Hashimoto, D. A, Vasisht, S., & Schaye, V. (2024). Demystifying AI: Current state and future role in medical education assessment. Academic Medicine, 99(4S), 42-47. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000005598

Weng, X., Xia, Q., Gu, M., Rajaram, K., & Chiu, T. K. F. (2024). Assessment and learning outcomes for generative AI in higher education: A scoping review on current research status and trends. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 40(6), 37-55. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.9540

Williamson, B., & Eynon, R. (2020). Historical threads, missing links, and future directions in AI in education. Learning, Media and Technology, 45(3), 223-235. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2020.1798995

Xia, Q., Weng, X., Ouyang, F., Lin, T. J., & Chiu, T. K. F. (2024). A scoping review on how generative artificial intelligence transforms assessment in higher education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 21(1), Article 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-024-00468-z

Zawacki-Richter, O., Marín, V. I., Bond, M., & Gouverneur, F. (2019). Systematic review of research on artificial intelligence applications in higher education—Where are the educators? International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 16(1), Article 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-019-0171-0

Nadia Delanoy is Assistant Professor and Director of Student Experience in the Werklund School of Education at the University of Calgary in Alberta, Canada. Her research interests include evidence-based practice in assessment, leadership, and innovative pedagogies in technology and AI-enhanced environments as well as big data and social media analytics to support innovative leadership practices. Email: nadia.delanoy@ucalgary.ca ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1761-9016