Georges-Louis Baron, Université de Paris, EDA, France

Solène Zablot, Université de Caen Normandie, CIRNEF, France

Online resources have become an important reality in education, accompanied by the phenomenon of the production, modification, and wide dissemination of educational resources by communities of teachers. This article explores the situation in France. First, we recall previous research on how teachers cooperate in order to create online resources. We distinguish between several types of collectives (captive communities, activist communities, proto-communities) and focus on their dynamics. Doing so implies considering the subjects as well as the instruments used and the social systems within which they evolve. Second, the issue of teacher agency relative to educational resources is analysed. In France, teachers are granted great freedom of pedagogical methods, a freedom not seen in all countries. Therefore, we analyse the activities of these collectives to understand how they view their activity and their role, specifically when using learning materials in class. An important related issue is the eagerness of administration to rely on evidence-based practice for orienting teacher action. We suggest that participatory research is a good investment for raising meaningful issues and proposing possible, short-term solutions.

Keywords: resources, teacher communities, theoretical frameworks

Les ressources en ligne sont devenues une réalité importante dans l’éducation, accompagnée d’un phénomène de production, de modification et de diffusion à grande échelle de ressources éducatives par des communautés d’enseignants. Cet article explore la situation en France. Tout d’abord, nous rappelons les recherches antérieures sur la façon dont les enseignants coopèrent pour créer des ressources en ligne. Nous distinguons plusieurs types de collectifs (communautés captives, communautés activistes, “proto-communautés”) et nous nous concentrons sur leur dynamique. Cela implique de considérer non seulement les sujets, mais aussi les instruments que ces sujets utilisent et les systèmes sociaux au sein desquels ils évoluent. Deuxièmement, la question de l’agence des enseignants par rapport aux ressources éducatives est analysée. En France, les enseignants jouissent d’une grande liberté en matière de méthodes pédagogiques, ce qui n’est pas le cas dans tous les pays. Nous analysons donc les activités de ces collectifs pour comprendre comment ils perçoivent leur activité et leur rôle, en particulier lorsqu’ils utilisent des ressources pédagogiques en classe. Une question connexe importante est l’empressement des administrations à s’appuyer sur des bonnes pratiques fondées sur des preuves pour orienter l’action des enseignants. Nous suggérons que la recherche participative est un bon investissement pour soulever des questions significatives et proposer des solutions possibles (à court terme).

Mots-clés : ressources, communautés d’enseignants, cadres théoriques

The idea of community has been much debated. From an etymological point of view, community (κοινότητα in Greek) shares a lot with society (κοινωνία), with the root κοινός indicating what is in common. Perhaps the first problematization of communities dates back to Tönnies (1987), at the end of the XIXe century, with a sharp distinction between Gemeinschaft (traditional communities, exploiting common goods with a strong solidarity) and Geselschaft (groups of people organised on the basis of contracts). From an economic and political perspective, the issue of the commons has raised different points of view, from the grim verdict of Hardin (1968), who discusses what he calls the tragedy of the commons, to the theses by Ostrom (1990) about what enables producer collectives to perform efficiently.

For our purpose, a community is considered a collective gathered around a common good, constituted either by a group of people combining their efforts or by an external impetus, which allows individual initiatives to unite their efforts. Many such communities exist in French education.

The typical classroom situation profile has slightly changed, even if the forme scolaire (the traditional model of the age-graded school) seems to be rather robust (Vincent, 2008). The role of textbooks is changing, and online resources tend to have a greater weight in education. These resources are produced and validated in different ways by an institution, company, community, or individual. This diversification has deep implications and calls for research into how educational resources are designed, produced, validated, and used. This discussion paper, which mostly relies on French examples, considers how teachers collectively design, produce, and share online educational resources (OERs).

Online educational resources have developed alongside progressive education. Dewey (2016) used the term often in his Democracy and Education, mainly as an antonym for an obstacle or difficulty, referring to a resource as something that allows one to cope with difficulties. However, he uses the word “textbook” far less often and, when he does, it is seldom in positive terms:

So far as schools still teach from textbooks and rely upon the principle of authority and acquisition rather than upon that of discovery and inquiry, their methods are Scholastic—minus the logical accuracy and system of Scholasticism at its best. (Dewey, 1916, Chap XX1, 1.)

The presence of OERs has spread rapidly since the beginning of the 21st century. These resources do not all follow the model of textbooks, even if textbooks, now digitised, often have digital complements (Gueudet et al., 2016). Something completely different may be offered, such as databases giving access to large amounts of information. The challenge is to go beyond the information given by relying on prior knowledge or external advice.

Digital resources have interesting, albeit potentially worrying, characteristics for education: almost anyone can produce, copy, transform, and widely disseminate them without any recognised authorisation, posing quality challenges. Bruillard and Baron (2018), studying issues linked to the design and evaluation of information, communication and technology (ICT) tools and resources for education in general, identified four key processes in the way teachers deal with online resources:

They also remark that teacher action “depends upon their degree of pedagogical freedom. Teachers collect resources and, most of the time, rearrange them for their students, composing something new from several sources, according to their choices and priorities” (Bruillard & Baron, 2018, p. 1147).

It is noteworthy that educational resource markets have appeared and are developing rapidly. In 2019, Amazon launched a new platform that allows teachers to sell OERs1, announcing that it “connects educational content creators with Amazon customers. Sell your original teaching resources—like printables, lesson plans, and classroom games—as digital downloads. It’s free to join”.

Resources may be produced and exchanged by people whose primary purpose is not monetary, but to produce free and open resources in the service of ideas and to create common goods and services. In France, Béziat (2003), Drot-Delange (2001), and Quentin and Bruillard (2013) studied these communities.

Our focus is to understand how teachers produce, modify, and disseminate pedagogical resources, drawing inspiration and strength from participating in a collective. What renders such collectives sustainable, how to study their development, and what factors favour it. What theories may be used to orient research in this domain? We focus on the theoretical aspects, suggesting that a mix of systemic theoretical models are needed, considering subjects, institutions, communities, and interactions. We extend a reflection first presented in Baron and Zablot (2017) within the French research project — REVEA (Bruillard, 2019).

First, we present a typology of collectives of teachers, distinguishing between captive, activist2, and proto-communities. Then we put into perspective several types of complementary theories and theoretical models that allow us to analyse the activity of producing and disseminating online resources.

Beauné et al. (2019) offer an analysis of the example of France, relying on data obtained in the national research REVEA project. They note that, in French, the word community first appeared in a religious context (before the historical separation of the catholic Church and the State in 1905). The word movement has been mostly used in a political context, and the word collective, for its part, is neutral and diverse in its meanings, while the word network is linked to an intricate organisation.

The French word communauté has two main meanings. Firstly, the term comes from its usage in mass media where it is linked with ethnic and religious affiliation. Secondly, in academia, the meaning is more flexible, referring to entities that are sometimes vague and equivalent to collective. For example, the expression communauté scolaire (school community) is often used to designate school participants and users, despite the interests and agenda differences of the categories of persons.

A collective of activists promotes didactical, pedagogical, and even political values (such as openness) not fully in line with those advocated by official bodies, such as the Ministry of Education in France (in particular, this is the case for activist communities). These transgressions, a sign of agentivity, are generally modest: we are not in a kind of counterculture but rather an environment of passionate innovators capable of anticipation and often benefiting, at least initially, from school institution support. This kind of community is commonplace in the French context, where teachers, by law, have a large autonomy in the choice of their methods.

Teacher collectives that produce resources are diverse and based on different models. Quentin and Bruillard (2013) studied such communities in France3 and distinguish two main organisation types, called the sandbox and the hive. For them, the rules for sandbox communities are flexible and not always clear. They also show a strong asymmetry of roles, with core persons occupying a central position and the others far from this core. In contrast, the hive has explicit operating rules and regular member interaction to achieve a common goal. From an economic point of view, Mengual-Andrés and Payá-Rico (2018) recall the three business models identified by OECD in a study of open education resources: community-based, philanthropy-based, and revenue-based.

The philanthropic model is “preferably to be adopted by foundations, governments and companies. Its financing is limited to donations and grants, with its sustainability linked to the financing received or the strategies anticipated by the possible donors” (Mengual-Andrés & Payá-Rico, 2018, p. 5). The revenue model depends on its ability to attract customers. Payments may be restricted to those who want to exceed a limited free offer.

We are interested in the dynamics of teacher collectives producing resources and will focus on several attractors that motivate these collectives. Our distinction is between captive communities, activist communities, and proto-communities.

The term captive is used in the sense of captive market4, i.e., communities existing only as long as there is support from an external institution. Captive teacher communities refer to situations where teachers are solicited by resource providers (private or public) to produce resources, which may be commercial or free depending upon the institution, in exchange for financial reward. For example, Baron and Zablot (2017) describe a working group of vocational teachers organised by the National Association for Automotive Training (ANFA), a private operator funded by the automobile profession. Created in 1952, this association is particularly present in apprenticeship training establishments (Centres de formation d’apprentis or CFA), where students share their time between the training centre and field experience where they are supervised by professionals.

In 1992, ANFA launched a training program for vocational teachers, asking the CFAs to participate in the Réseau des CFA pilotes (Pilot CFA) network. Since 2010, the Association has held the right, in partnership with the Ministry of National Education, to offer resources to teachers. To this end, ANFA involves teachers in designing these resources and compensates CFAs for the costs of inviting teachers to take part. Training centre network members have reserved access to resources stored on an Extranet during previous working groups. These online resources can be uploaded to the Educauto website, which is run by both the Association and the Ministry of National Education.

Many teacher communities attract pedagogical activists who produce online resources. Unlike captive communities, activist communities are founded on shared values and promote principles such as pedagogical liberty. This is a historical principle enshrined in France’s national education code but it is also a fragile reality5.

One example of an activist community is the Institut coopératif de l’école moderne (Coop’ICEM) which was founded by the famous French pedagogue, Freinet. He was an important pioneer of student-centred pedagogy which was promoted as individualised learning (Acker, 2000; Freinet, 1990). This community was an early producer of paper resources, notably in the form of bibliothèques de travail (working libraries) and non-behaviourist programmed learning materials (bandes enseignantes). They were also among the first to start using online resources.

In contrast with the pilot CFAs network, which is subsidised by ANFA, activist communities like ICEM are not organised by an official institution and, in most cases, the resources produced are free and open. For example, Groupe Français d’Education Nouvelle (GFEN), an activist collective with the slogan All able! All researchers! All creators!, was similarly created during the Freinet movement (around 1920) and follows a Démarche d’Auto-Socio-Construction des savoirs (DASC; auto-socio construction of knowledge) approach, aimed at enabling students to build their own knowledge (through engaging with peers). It is organised into several thematic, geographic, and disciplinary groups.

Beauné et al. (2019) studied the way an activist collective specialised in language learning. Taking an ethnographic approach, they remarked that the modification of resources is like a goldsmith’s work but that the resources themselves are not important for the collective members. What matters is the process. They state:

Authors of resources may be compared to heroic figures who, each in her own style influence the community. This influence is however not oriented towards auto-promotion or improvements in the career. On the contrary, it seems associated with strong, quasi sacrificial values [...] this commitment aims toward the development of commons of knowledge (p. 232)6.

Sesamath is another example of an activist community evolving toward something different. Founded in 2001, Sesamath has gained influence in France by selling paper textbooks and offering free and paid-for premium online resources. Sesamath has created a trend with other associations implementing similar models.

Communities do not build themselves. We have discussed the emergence of informal online teacher collectives or proto-communities (Baron & Zablot, 2017). These collectives emerge from personal initiatives that gradually attract a nucleus of innovative colleagues who share common interests and affinities. They start modest actions to produce and diffuse resources outside established structures, generally for free, at least initially. For example, in France, some teachers create profiles on social networks, like Facebook and YouTube, to share classroom activity examples. These communities often have a limited duration and changes in their organisation frequently occur, a powerful attractor being commercial companies.

For example, Carton (2019) observed an interesting permeability between a teacher proto-community publishing resources on personal websites and a firm subsequently offering incentives to produce educational kits for the company, thus the teachers became recognised authors and received both material and symbolic benefits. In this case, the relationships between participants were modest. Consequently, the teaching community is weak and dependent on the company. It is a pseudo-community.

An example of a proto-community that later became a business is lelivrescolaire.fr. As of 2024, this company presented itself as a publisher founded in 2009 by a teacher interested in digital textbooks “we came up with the crazy idea of creating field textbooks, produced collaboratively by teachers and available free of charge on the internet”7. It claims to constitute a community producing textbooks that are written collaboratively (collaboration being for them a cardinal value), with free online access and premium solutions accessible for a fee without Internet access or on paper.

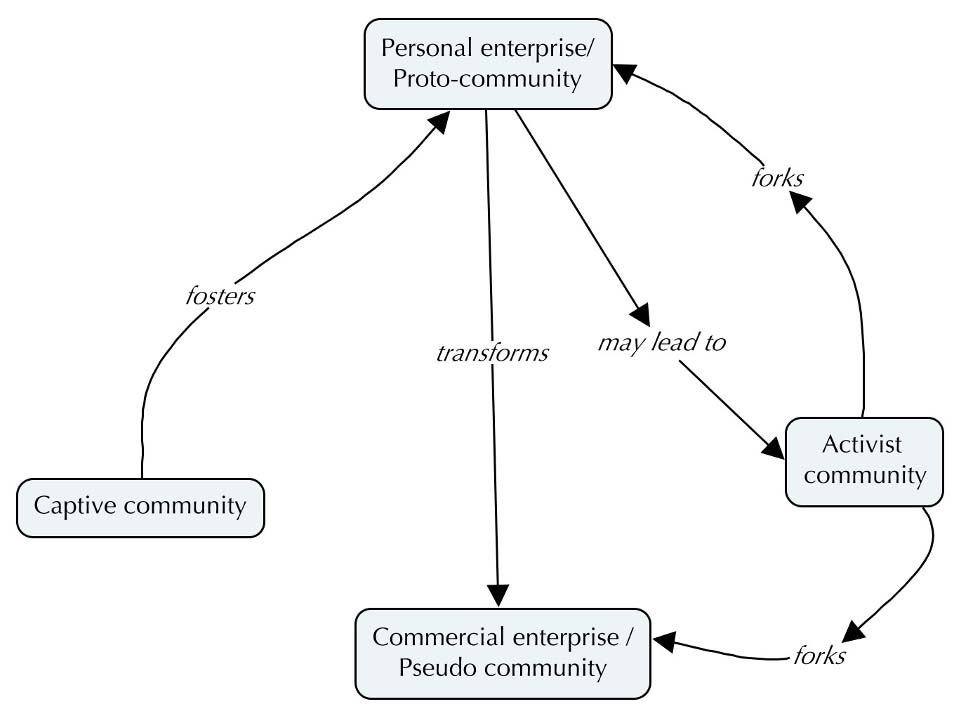

Based on the analysis of captive, activist, and proto-communities, Baron and Zablot (2017) developed a model that illustrates several forms of evolutions from one type of collective to another.

Figure 1

Model of the Transformational Flux Between Different Types of Teacher Communities

Note. Baron & Zablot, 2017, p. 33.

Often splits occur within these latter activist communities with some members joining a commercial enterprise or founding another proto-community. Captive communities often play a role in training teachers, some of whom may later embark on their own projects. These new proto-communities may have originated within a captive community and, as seen before, evolve. They can either dissolve into a pseudo-community or adhere to an activist community with whom they share affinities.

Social networks are changing the way teachers create new proto-communities by means of new functionalities of the Internet, and in particular, teacher activity tends to be more individual. Instagram, the social network created in 2010, is increasingly used by companies to showcase their products and/or services8 and to facilitate commercial activity9. This activity, known as influence marketing, involves exploiting users’ fame to sell products. Influencers promote products by creating short videos or posting photographs on their social media feeds10.

Another type of economic activity exists, that of a content creator. However, differences between the terms content creator and influencer are not clear. In French law (2023), the two terms were grouped together under the heading activity of commercial influence and designate: “any natural or legal person whose activity consists, for consideration (in kind or in financial form), in creating and producing content aimed at promoting goods or services of which he is not necessarily the producer or provider, disseminated by means of digital communication, on the occasion of the expression of his personality”. Content creators can be small or intermediate companies or individuals such as lifestyle coaches who have partnerships with companies to promote their products.

Zablot (2023) published preliminary research on teachers who share resources on Instagram. Zablot remarks that some primary teachers use similar strategies to influencers to promote themselves and show their practices in class (like lifestyle coaches). Zablot distinguishes three profiles—archivists, experimenters, and influencers—that reflect how these teachers organise their content and their eventual partnerships with companies:

In this context, proto-communities continue to emerge on this network, with the sharing of resources such as lessons and class activities ensured on teacher-designed websites. However, there are no signs of evolution towards a militant community. Instagram serves as a showcase: followers can collect resources by clicking on the website link created by the teacher and posted on the account.

Some teachers use their fame to capture the attention of publishing companies that produce educational resources (e.g., Nathan). The number of account followers becomes a recognised commercial element leading to authoring textbooks published by these companies. In this case, the links between teachers remain loose and social networks are used to promote personal careers, even if the motive is sharing resources.

The findings show that teacher communities may form and innovate in a sustainable and affordable way to improve teaching by using new technological possibilities when conditions are favourable. This is confirmation of a well-established trend and not a new result.

In France, teacher agency is a historical fact. Most teachers have tenure, and there is a culture of public service and sharing among teachers. They must follow the national curriculum but benefit from freedom in pedagogical methods. To what extent does this finding exist elsewhere?

Fundamentally, this is a question of teacher agency, which therefore has a strong political dimension and is answered differently according to national histories. While administrations can influence textbook production, directly or indirectly, they cannot easily control the creation and usage of online resources, which depend upon global technical infrastructure.

The question of educational resources has gained a new actuality with the development of digital technology (Mochizuki & Bruillard, 2019). It is suggested that technology will allow for educational paradigm shifts, with the notion of “transformative learning”, “the kind of learning that enables learners to go beyond the status quo and transform societies for the better” (p. 7). The perceived stakes are a transformation of traditional schooling methods. But which of these transformations are feasible?

Ideas about the necessity or ineluctability of de-schooling society and moving toward other forms of transmission between generations have been published since the early 1970s. Illich (1971) famously denounced the awful aspects of traditional schools and certified teachers, pleading for this disruption and advocating the need for something completely different:

The current search for new educational funnels must be reversed into the search for their institutional inverse: educational webs which heighten the opportunity for each one to transform each moment of his living into one of learning, sharing, and caring. (p. 2)

This manifesto aroused interest but had no practical consequences: schools and school systems are remarkably homeostatic. However, the idea of learning outside the school structure has gained momentum, with renewed interest in non-formal and informal learning (Schugurensky, 2000).

Although specialists in disruptive innovation, such as Christensen et al. (2008), predicted a disruption to educational systems due to technological innovation, this has not occurred. Documents and resources for teaching and learning in different forms, economic models, and use cannot be predicted. A key question is how teachers can use, modify, design, and disseminate educational resources for their students in a creative way.

In democratic countries, one possible means of innovation is through participatory research.

Education research holds a broad concept with many possible finalities. Among them, two are in tension: (1) evaluating educational actions to inform decision-makers and disseminate good practice and (2) understanding what is happening, identifying the main problems, and inventing possible ways to circumvent them.

Recently, we have seen some governments trying to control teachers’ actions by promoting methods that have arguably been proven to work. This political trend may be tracked to the USA in the early 2000s and the seminal policies of the No Child Left Behind law launched by G.W. Bush’s administration. Since then, the focus has been on school and teacher accountability, with unexpected consequences, like different forms of cheating in order to achieve good results in high-stake tests (Amrein-Beardsley et al., 2010).

In France, a scientific council for national education, created in 2016, clearly advocates pedagogies like direct instruction and calls for a coordination of educational research. Until now, however, it has had limited impact on teacher action. The general idea is to obtain evidence-based research proving the efficiency of certain educational interventions. This research is conducted from above the practitioners, who are the subjects being observed. The dominant interest is in what counts as a proof of causality, the gold standard being randomised control trials (RCTs) comparing different groups of people subjected to different treatments.

In education there has been strong criticism of policies for evaluating the efficacy of educational interventions, which Pogrow (2017) presents as a failure of effective practices policies. Among his criticisms are the fact that this research has critical flaws, such as relying on relative comparisons only, adjusted outcome scores, or considering a threshold for effect size (.2) that is too small to be easily detected.

This methodology leads to confusion in the research and journalistic communities as to whether programs are producing actual (i.e., unadjusted, non-relative, non-normalized) improvement levels of student performance that are apparent in the real world. [...] These problems provide a basis for explaining why prior iterations of implementing effective practices policies. (p. 12)

More generally, Deaton and Cartwright (2018) observe that RCT research is not very strong for inferring what works in other contexts. They remark that:

The need for observational knowledge is one of many reasons why it is counter-productive to insist that RCTs are the gold standard or that some categories of evidence should be prioritized over others; these strategies leave us helpless in using RCTs beyond their original context. The results of RCTs must be integrated with other knowledge, including the practical wisdom of policymakers, if they are to be useable outside the context in which they were constructed. (p. 30)

The idea of normalising research by financing RCTs is not specific to Western countries. A report by the Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel (GEEAP, 2023), focused on the situation of low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), identifying great and bad buys based on evidence-based research. They offer a series of evaluations on educational interventions from an estimation of cost effectiveness. Their report is based on the convincing power of rigorous evaluative research considered as able to distinguish the causal effect of an intervention. Given the degree of causality established, to what extent can examples of good practice convince practitioners?

The situation is different in LMICs. Smart (2021) addresses the issue of teacher guides in the context of direct and scripted instruction. He notes that there is growing interest among international institutions and agencies to exert a greater influence on classroom practice to improve learning outcomes by prescribing how teachers should act in the light of research findings. This position has been held in LMICs and OECD countries and has been part of a long-standing debate about the merits and effects of prescribing methodology. Smart stresses that studying and developing effective teacher guides should be done in cooperation with practising teachers. He judiciously remarks that:

A theory of change or improvement that communicates to teachers that policymakers have no confidence in them is unlikely to win over those on whom the policymaker counts most to make the improvements happen. (Smart, 2021, p. 18)

Whatever the technological advances, teachers will continue to instruct new generations.

The persuasive power of evidence-based research for practitioners is another key issue. Nelson (2021) remarks that evidence collected about the institution established by the G.W. Bush administration, the WWC, showed that it struggled to reach its intended users, and for those it did reach, its outputs were likely perceived as irrelevant.

A similar finding was published by Riordan (2023) based on a substantial British empirical study of policies designed to improve educational outcomes of students facing socio-economic disadvantages. Riordan remarks that “the determination to base school practice on research and the political motivation to improve social mobility—are failing to deliver their intended consequences” (p. 5).

The question of proving and disseminating these research results, and the process of constructing research questions, remains open. Research approaches that consider elements of a particular situation exist. It is important to consideration that their conceptual orientations are fruitful when served by an adapted methodology, and that each methodology has its own limitations. For instance, questionnaires administered only once are insufficient for explaining processes; and external analyses of textbook and resource collections without studying their implementation are also partial. While participatory research may bring interesting results and inspire practitioners, it cannot be generalised or replicated. These limitations may not be important when the aim is not to predict outcomes or establish guidelines, but rather to understand the changes occurring in groups operating in areas where new forms of teaching expertise are being built, and where individuals collaborate to produce shared resources.

Sharing experience online goes beyond merely sharing resources. Through social networks, teachers may become a resource for younger colleagues, thus improving the profession’s global agentivity. Baron and Fluckiger (2021) argue that developing multidisciplinary and multi-cultural forums for practitioner and researcher exchange to consolidate networks of diverse communities with a shared interest is important for forming sustainable hybrid collectives. While not an easy task and will not guarantee the sustainability of innovations in OERs, it will allow interesting ideas to be explored.

Acker, V. (2000). Celestin Freinet (1896-1966): A Most Unappreciated Educator in the Anglophone World.

Amrein-Beardsley, A., Berliner, D. C., & Rideau, S. (2010). Cheating in the first, second, and third degree: Educators’ responses to high-stakes testing. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 18, 14. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v18n14.2010

Baron, G.-L. & Fluckiger, C. (2021). Approaches and paradigms for research on the educational uses of technologies: Challenges and perspectives. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 47(4). https://doi.org/10.21432/cjlt28059

Baron, G.-L. & Zablot, S. (2017). From building personal resources to creating formal communities: A case study from France. Review of Science, Mathematics and ICT Education, 11(2), 27-45. https://hal.science/hal-01671526v1

Bathelot, B., (2015). Marché captif. Définition Marketing, ‘L’encyclopédie illustrée du marketing’. https://www.definitions-marketing.com/definition/marche-captif/

Beauné, A., Levoin, X., Bruillard, E., Quentin, I. C., Zablot, S., Carton, T., Rouvet-Song, C., Normand-Assadi, S., Roy, M. L., Nikishina, T., Mas-Costesèque, S., & Baron, G.-L. (2019). Networked collectives of resource-producing teachers. Scientific report by STEF and EDA laboratories under the DNE agreement. https://hal.science/hal-02022830v1

Béziat, J. (2003). Computer technologies in elementary school. From reforming modernity to innovative pedagogical integration. A contribution to the study of modes of inflection, support and accompaniment of innovation. [Ph.D, Université Paris Descartes]. TEL Archives ouvertes. https://theses.hal.science/file/index/docid/437088/filename/These_JBziat.pdf

Bruillard, E. (2019). Understanding teacher activity with educational resources. Selection, creation, modification, use, discussion and sharing. IARTEM 1991-2016: 25 years developing textbook and educational media research, 343-352. https://iartem.ucl.dk/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/iartem_25_years.pdf#page=343

Bruillard, E. & Baron, G.-L. (2018). Researching the Design and Evaluation of Information Technology Tools for Education. In Voogt, J., Knezek, G., Christensen, R., & Lai, K. W. (eds). Second Handbook of Information Technology in Primary and Secondary Education, 1-17. Springer International Handbooks of Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-53803-7_79-1

Carton, T. (2019). A Case Study of Cooperation between Teachers and EdTech Companies: LeWebPédagogique. IARTEM E-Journal, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.21344/iartem.v11i1.588

Christensen, C. M., Johnson, C. W., & Horn, M. B. (2008). Disrupting Class. How Disruptive Innovation Will Change the Way the World Learns. McGraw-Hill.

Deaton, A. & Cartwright, N. (2018). Understanding and misunderstanding randomized controlled trials. Social Science & Medicine, 210, 2-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.12.005

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education. An introduction to the philosophy of education. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/852/852-h/852-h.htm

Drot-Delange, B. (2001). Outils de communication électronique et disciplines scolaires: quelle(s)rationalité(s) d’usage ? Le cas de trois disciplines du second degré : la technologie au collège, l’économie-gestion et les sciences économiques et sociales au lycée. [Electronic communication tools and school subjects: which rationality(ies) of use? The case of three secondary school disciplines: technology in junior high school, economics and management, and economic and social sciences in high school]. [PhD École Normale Supérieure de Cachan]. TEL Archives ouvertes. https://theses.hal.science/tel-00381040

Freinet, C. (1990). Cooperative Learning & Social Change: Selected Writings of Célestin Freinet. James Lorimer & Company Ltd. Publishers.

Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel (GEEAP). (2023). Cost-effective approaches to improve global learning. What does recent evidence tell us are “Smart Buys” for improving learning in low- and middle-income countries? (p. 67) [Recommendations of the Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel (GEEAP)]. World Bank Group. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099420106132331608/pdf/IDU0977f73d7022b1047770980c0c5a14598eef8.pdf

Gueudet, G., Pepin, B., & Trouche, L. (2016). Manuels scolaires et ressources numériques : vers de nouvelles conceptualisations. [Textbooks and digital resources: towards new conceptualizations] Revista de Educação Matemática e Tecnológica Iberoamericana, 6(3). https://hal.science/hal-01346646v1

Hardin, G. (1968). The Tragedy of the Commons. Science, 162(1968), 1243-1248. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.162.3859.1243

Illich, I. (1971). Deschooling Society. Harper & Row. https://web.archive.org/web/20081121191010/http://ournature.org/∼novembre/illich/1970_deschooling.html

Mengual-Andrés, S. & Payá-Rico, A. (2018). Open Educational Resources’ Impact and Outcomes: The Essence of OpenKnowledge and its Social Contribution. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 26, 119. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.26.3667

Mochizuki, Y., & Bruillard, É. (Éds.). (2019). Rethinking pedagogy. Exploring the potential of digital technology in achieving quality education. Unesco / MGIEP. https://d27gr4uvgxfbqz.cloudfront.net/files%2Fa704b5df-1a8a-4059-beb0-19843d51f5ff_Rethinking%20Pedagogy.pdf

Nelson, A. A. (2021). Is What Works Working? Thinking Evaluatively About the What Works Clearinghouse. https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2021.052

OECD, 2007. Giving Knowledge for Free: The Emergence of Open Educational Resources. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264032125-en

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: the evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press.

Pogrow, S. (2017). The failure of the U.S. education research establishment to identify effective practices: Beware effective practices policies. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 25(0), 5. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.25.2517

Quentin, I. & Bruillard, E. (2013, March). Explaining internal functioning of online teacher networks: between personal interest and depersonalized collective production, between the sandbox and the hive. In Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference (pp. 2627-2634). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE).

Riordan, S. (2022). Improving teaching quality to compensate for socio-economic disadvantages: A study of research dissemination across secondary schools in England. Review of Education, 10(2), e3354. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3354

Schugurensky, D. (2000). The forms of informal learning: Towards a conceptualization of the field (WALL Working Paper No.19). Centre for the Study of Education and Work. https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/handle/1807/2733

Smart, A. (2021). Teachers’ guides: Isn’t that what they should be? IARTEM E-Journal, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.21344/iartem.v13i1.971

Tönnies, F. (1987). Communauté et société. Catégories fondamentales de la sociologie pure. [Community and society. Basic categories of pure sociology]. Presses universitaires de France.

Vincent, G. (2008). La socialisation démocratique contre la forme scolaire. [Democratic socialization versus the school form]. Éducation et francophonie, 36(2), 47-62. https://doi.org/10.7202/029479ar

Zablot, S. (2023). Quelles pratiques d’enseignants du primaire sur Instagram ? A propos du partage d’expériences et de ressources sur les réseaux sociaux. [What practices do primary school teachers use on Instagram? About sharing experiences and resources on social networks]. (oral communication). Colloque Etic 5, ‘école et TIC’ – université de Caen Normandie, 9-11 octobre 2023.

Georges-Louis Baron is professor emeritus of education at Université Paris Cité. He has published on educational technology and its history, as well as, on the didactic issues involved in teaching computer and digital skills, especially in elementary school. His current research focus is on new forms of learning linked to peer cooperation around social networks. Email: Georges-louis.baron@u-paris.fr

Solène Zablot is associate professor of education at the university of Caen Normandie. Having studied the use of digital resources by vocational training teacher collectives for her PhD, she is now investigating how students and teachers use social networks for non-formal learning. Email: solene.zablot@gmail.com