Ann-Kathrin Grenz, Fraunhofer Institute for Applied Information Technology FIT, Germany

Soroush Sabbaghan, University of Calgary, Canada

Michele Jacobsen, University of Calgary, Canada

The rapid emergence of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) tools presents new opportunities and challenges for higher education, yet little is known about how undergraduate students choose to engage with these technologies. This study examined Canadian undergraduates’ perspectives on GenAI as a learning support across three phases of the lecture cycle: before, during, and after class. Using a mixed-format survey (N = 296), we analyzed 118 student-written responses through Mayring’s qualitative content analysis and mapped themes onto Zimmerman’s model of Self-Regulated Learning (SRL). Results indicate that students see GenAI as a versatile cognitive partner—supporting preparation before lectures, engagement and clarification during, and review and assignment help afterward. Students also expressed critical concerns about overreliance, accuracy, academic integrity, and data privacy, which align with vulnerabilities in SRL processes such as self-control, self-evaluation, and help-seeking. Findings highlight a conceptual shift from institutional framings of GenAI as a production tool toward student framings of GenAI as a mechanism for intellectual capacity building. We argue that deliberate integration of GenAI into teaching practices and institutional policies—aligned with SRL subprocesses—can support responsible, student-informed adoption. The study contributes timely evidence for educators and policymakers navigating the pedagogical and ethical dimensions of GenAI in postsecondary learning.

Keywords: generative artificial intelligence, higher education, qualitative research, self-regulated learning

L’émergence rapide des outils d’intelligence artificielle générative (IAg) présente à la fois de nouvelles opportunités et des nouveaux défis pour l’enseignement supérieur, toutefois, on en sait encore peu sur la manière dont les personnes étudiantes de premier cycle choisissent d’utiliser ces technologies. Cette étude a examiné les perspectives de personnes étudiantes canadiennes de premier cycle quant au rôle de l’IAg comme soutien à l’apprentissage tout au long des trois phases du cycle d’un cours magistral : avant, pendant et après le cours. À l’aide d’un sondage mixte (n = 296) nous avons analysé 118 réponses écrites par les personnes étudiantes à l’aide de l’analyse de contenu qualitative de Mayring et avons cartographié les thèmes dégagés avec le modèle d’autorégulation de l’apprentissage de Zimmerman. Les résultats indiquent que les personnes étudiantes conçoivent l’IAg comme un partenaire cognitif polyvalent qui les aide à se préparer avant les cours, à participer et à clarifier des points pendant les cours, et à réviser et avoir de l’aide avec les devoirs après les cours. Les personnes étudiantes ont également exprimé des préoccupations critiques liées à la dépendance excessive, à l’exactitude des réponses, à l’intégrité intellectuelle et à la protection des données, lesquelles correspondent aux vulnérabilités dans les processus d’autorégulation tels que le contrôle de soi, l’autoévaluation et la recherche d’aide. Les résultats mettent en évidence un changement conceptuel passant d’une conception institutionnelle de l’IAg comme outil de production à une conception étudiante de l’IAg comme mécanisme de renforcement des capacités intellectuelles. Nous soutenons qu’une intégration intentionnelle de l’IAg dans les pratiques pédagogiques et les politiques institutionnelles—alignée sur les sous-processus de l’autorégulation de l’apprentissage—peut favoriser une adoption responsable et éclairée par les personnes étudiantes. Cette étude apporte des données probantes et opportunes pour les personnes enseignantes et les responsables institutionnels qui naviguent entre les dimensions pédagogiques et éthiques de l’IAg dans l’apprentissage postsecondaire.

Mots-clés : intelligence artificielle générative, enseignement supérieur, recherche qualitative, apprentissage autorégulé

The rapid emergence of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) tools presents both opportunities and challenges for teaching and learning in higher education. Recent studies, such as those by Bittle and El-Gayar (2025) and Wu and Chiu (2025), are shedding light on the ways that GenAI use in postsecondary education is influencing teaching practices, academic integrity, and institutional policies. Yet far less attention has been given to how undergraduate students themselves are navigating and making sense of these tools individually as part of their learning. This gap matters because students are not only the primary users of GenAI in academic contexts, but also the ones whose practices ultimately determine the success of institutional policies and classroom integration (Qu et al., 2024; Soliman et al., 2025; Xu et al., 2025). Understanding their perspectives and practices is therefore critical for aligning technological innovation with pedagogical intent.

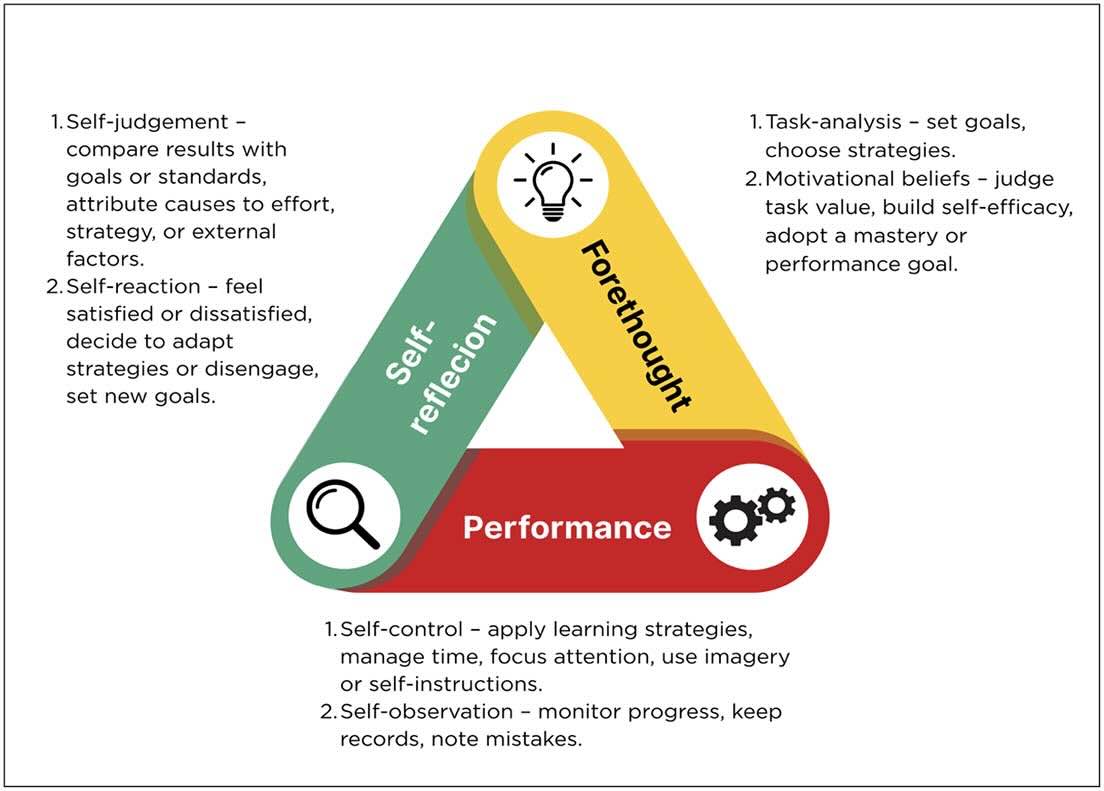

Few studies have invited students to describe, in their own voices, how GenAI supports, or could ideally support, their engagement with lectures. In particular, little is known about how students view GenAI across different phases of the learning cycle (before, during, and after class), and how these perspectives connect to broader processes of self-regulated learning (SRL). Zimmerman’s (2000) SRL model provides a useful framework for interpreting student expectations of GenAI, as it highlights the cyclical interplay of forethought, performance, and self-reflection. Positioning GenAI within this framework allows us to examine not only how students use these tools, but also how they envision them as supports or potential risks for autonomy, strategy use, and evaluative judgment.

This study addresses these gaps by investigating Canadian undergraduates’ perspectives on GenAI as a learning support. Our analysis focuses on two guiding research questions:

By mapping students’ reported uses and concerns onto Zimmerman’s SRL framework, this study makes two contributions. First, it offers one of the earliest Canadian investigations that systematically integrates student perspectives with a well-established model of self-regulated learning. Second, it provides evidence for a conceptual shift: while institutions often frame GenAI primarily as a production tool, students increasingly view it as a cognitive partner for intellectual capacity building. These insights carry important implications for teaching and policy. Understanding how students conceptualize GenAI can inform more deliberate course design, guide the development of AI literacy initiatives, and support institutional policies that balance innovation with ethical responsibility.

In higher education, leveraging GenAI offers exciting benefits to learners, educators, and researchers. However, alongside these benefits are significant risks involving potential unethical, inappropriate, or incorrect use of these tools. Canadian researchers, e.g. Ally and Mishra (2025) and Chambers and Owen (2024), emphasize the urgent necessity for educational institutions to establish and enforce guidelines, policies, and standards for GenAI's application in higher education (Ally & Mishra, 2025). They advocate for advancing digital literacy across all academic sectors, including ethical usage guidelines pertinent to teaching, learning, assessment, and research. Responding to this call, an Australian team developed the "AI Literacy: Principles of ETHICAL Generative Artificial Intelligence" resource (Eacersall et al., 2024), which seeks to provide a principled framework to develop GenAI literacies and offer pragmatic ethical guidance for researchers addressing the intricate challenges posed by GenAI-enhanced research.

A survey conducted by Shaw et al. (2023) involving 1,600 postsecondary students and 1,000 faculty members revealed a notable usage gap. More than twice as many students (49%) as faculty (22%) reported using GenAI, with usage trends rising among both groups. Furthermore, a U.S. survey involving 361 undergraduates indicated that two-thirds perceive GenAI as enhancing learning, provided it is employed responsibly and ethically (Holechek & Sreenivas, 2024).

Ally and Mishra (2025) propose several critical policy considerations for AI in higher education, which range from technological access and data privacy to AI ethics, teaching methodologies, academic integrity, cost implications, and sustainability. They underscore the importance of institutions setting clear AI policies and investing in educational programs and training to foster AI competencies, thereby enhancing learning, teaching, and research priorities.

In this study, we delved into understanding how Canadian undergraduate students navigate the use of GenAI supports around their lectures and their concerns about GenAI in higher education. We also aimed to identify the types of support that can maximize students' effective use of GenAI tools for learning. Research synthesis reveals intriguing trends in GenAI utilization; for instance, a large-scale survey from China highlights widespread academic use across various educational settings (Yang et al., 2025). Additionally, experimental studies have shown that GenAI can significantly enhance learning outcomes when aiding task completion (Yang et al., 2025). Comprehensive behavioural analyses also emphasize diverse usage patterns among students from content creation and metacognitive prompts to language refinement, especially in autonomous learning and STEM-related environments (Ammari et al., 2025; Sajja et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2024).

It is crucial to recognize that GenAI's role spans numerous learning activities at the undergraduate level. Golding et al. (2024), in their exploration of college students’ engagement with GenAI, found students were well-acquainted with these tools but primarily sought them for assignment assistance. Johnston et al. (2024) discussed students' views on technologies like ChatGPT, revealing general hesitance toward using GenAI for writing entire essays, with a call for universities to facilitate meaningful integration. Factors such as perceived usefulness and autonomy emerge as pivotal predictors in students' decisions to use GenAI educationally (Soliman et al., 2025). Tang et al. (2025) similarly identified facilitating conditions and social influence as significant drivers of this adoption. Through these insights, we connect with the evolving landscape of GenAI in academic settings, inviting thoughtful conversation and innovation.

Specific applications of GenAI in education are catching attention across the academic landscape. Johnson and Doss (2024) discovered that undergraduate agriculture students adeptly engaged ChatGPT for microcontroller programming, highlighting its role in technical disciplines. Guillén-Yparrea et al. (2024) shed light on GenAI's resonance within higher education, particularly among engineering cohorts, revealing a prevalent use of ChatGPT but also noting the less enthusiastic perspective of their professors. This discussion continues with Sun and Zhou (2024), who emphasize in their meta-analysis how students are harnessing GenAI for both learning and academic performance enhancement. Other vital factors, such as AI literacy and varying disciplinary norms, surface through the investigations of Wang et al. (2024) and Qu et al. (2024), painting a broader picture of this evolving educational tool.

Diving into studies from various fields, we find undergraduates employing GenAI in manifold ways to bolster their learning journey, both within and outside the classroom. For instance, Chambers and Owen (2024) detail how introductory psychology students used chatbots to clarify complex concepts, prepare for exams, and assist in essay tasks. Additionally, Hamerman et al. (2025) engaged with 115 U.S. business students in a survey and a subsequent case study, illustrating GenAI’s impact on homework approaches. Razmerita's (2024) interviews investigate business students' chatbot adoption, balancing the benefits and challenges it presents. Comprehensive analyses, utilizing case studies, intervention, and various mixed methodologies, paint a vibrant landscape owing to scholars like Aure and Cuenca (2024), Holecheck and Sreenivas (2024), Huang et al. (2024), and Johri et al. (2024). Through these collective explorations, encompassing over 900 students, GenAI emerges as a compelling academic ally.

In exploring the variety of GenAI tools used in academic environments, ChatGPT emerges frequently in the literature. However, individual studies have also highlighted the application of other tools, such as Bard, Gemini, Perplexity, Elicit, Tiimo Vercel, My AI, essaywriters.ai, Microsoft Bing, Dall-E, Midjourney, Copilot, and Claude. These tools serve multiple roles, particularly as brainstorming partners, writing tutors, and real-time feedback coaches (Aure & Cuenca, 2024; Hamerman et al., 2025; Rasmerita, 2024). Their use spans various phases of education, evident in business education, introductory psychology, undergraduate research methods, and technology courses, both before and after lectures (Aure & Cuenca, 2024; Chambers & Owen, 2024; Huang et al., 2024; Johri et al., 2024).

What insights can we gather directly from students about the utilization and benefits of GenAI tools? Undergraduate students, in various studies, express that these tools significantly enhance their research efficiency by simplifying the extraction of key findings and unraveling complex concepts, thus improving comprehension (Aure & Cuenca, 2024; Chambers & Owen, 2024). They further note improvements in academic writing, exam performance, and the generation of writing ideas while analyzing large datasets (Hamerman et al., 2025; Holechek & Sreenivas, 2024). These tools facilitate studying through diverse formative e-assessments and boost overall productivity by providing prompt responses and fostering personalized, collaborative learning opportunities (Johri et al., 2024).

Students who feel they benefit from GenAI tend to use it more frequently. Hamerman et al. (2025) found a correlation between students' perceived peer usage and their own GenAI utilization. Gender differences are apparent too, with males using these tools more often, although perceptions of GenAI as academic dishonesty deter usage. Johri et al. (2024) highlighted awareness among students about potential pitfalls such as inaccuracies and overreliance, alongside ethical concerns like cheating and privacy risks. Rasmerita (2024) emphasizes that despite these challenges, students overwhelmingly believe GenAI benefits outweigh its drawbacks, enhancing learning if used appropriately, though they note concerns like flawed referencing and ethical dilemmas.

Proactive teaching strategies are key to integrating these tools effectively. Studies recommend scaffolded assignments, critical evaluation, and metacognitive reflection to mitigate ethical and academic integrity concerns, promoting a balanced approach to GenAI use in educational contexts (Johri et al., 2024).

Given the study’s aim to capture broad patterns in how undergraduate students use GenAI as a learning support, as well as to gather more detailed perspectives in their own words, we employed a mixed-format survey methodology that combined select-response and open-ended questions. This approach was selected for its ability to balance breadth and depth: the structured, close-ended items enabled us to map usage patterns across a larger and more diverse group of students, while the open-ended prompts provided richer qualitative insights into students’ expectations, practices, and concerns. We contend that this survey design is particularly suited to emerging areas of educational technology research, where exploratory evidence is needed both to identify widespread trends and to surface nuanced, context-specific perspectives. Given our focus on student use patterns, we did not include questions on the learning modality or the instructor’s role.

The survey design allowed us to capture students’ reflections across the full lecture cycle before, during, and after class thereby situating GenAI use within the temporal rhythm of academic learning. This framing was informed by SRL theory, which emphasizes the cyclical interplay of forethought, performance, and reflection. By aligning survey questions with these phases, we were able to explore not only the functional tasks students associate with GenAI, but also the metacognitive and motivational processes they perceive it to influence. The combination of quantitative and qualitative data therefore provided a multidimensional picture of student engagement with GenAI, enabling us to examine both the prevalence of practices and the meanings students ascribe to them.

Ethical approval of the study protocol was granted, and participants were recruited from undergraduate programs at a large research university in Western Canada. The team combined digital and in-person recruitment strategies to maximize outreach and response rates. An invitation to participate in an anonymous online survey was disseminated via email to all associate deans and department heads of undergraduate programs across all disciplines, with a request to forward the questionnaire link to undergraduate students. While this method allowed for broad potential reach, the response rate to email recruitment was low.

A supplementary recruitment strategy had members of the research team visiting several busy areas on campus to approach students directly with a flyer inviting them to complete the survey. We also distributed the flyer, with a brief study description and QR code that linked to the survey, in high-traffic areas. This face-to-face method and use of flyers proved significantly more effective in generating responses, as it allowed for immediate engagement and clarification of the study’s purpose, thereby increasing rates of student participation. Overall, 296 students submitted survey responses, and were only allowed to enter once. In this paper, we focus analysis on the 118 textual responses that participants submitted to four open-ended survey questions.

In exploring how students conceptualize the ideal GenAI support surrounding their lectures, we utilized Mayring’s (2014, 2021) qualitative content analysis as our guiding methodology. This structured method enables an inductive analysis of textual data, facilitating the iterative categorization and interpretation that helps uncover underlying themes. We examined responses aligned with four open-ended questions: Ideal Support Before a Lecture (24 responses), Ideal Support During a Lecture (16 responses), Ideal Support After a Lecture (44 responses), and Student Concerns about AI (34 responses). Mayring’s criteria were applied uniformly to each question set, as exemplified through the analysis of data from the Ideal Support Before a Lecture section. Following Mayring’s structured approach, our initial step involved defining the analytic material as comprising 24 written statements from students responding to the survey question on ideal GenAI support before lectures. These data were collected within a broader online questionnaire addressing students' experiences and expectations with GenAI in higher education. Each bullet-pointed response was treated as an individual coding unit, facilitating a clear, inductive analysis. Our goal was to derive meaningful categories and reveal thematic patterns, capturing participants’ expectations for GenAI’s role in preparing for learning experiences.

In considering our conceptual framework, our analysis was guided by the research questions we posed. We embraced an inductive category development approach to organically generate categories directly from our data. To achieve this, we engaged in a systematic procedure of paraphrasing, generalization, and reduction of individual statements to encapsulate their essential meanings, ultimately forming overarching categories. We valued every bullet-point statement as a coding unit, each one representing a distinct insight or perspective shared by a participant. For example, statements were paraphrased to reveal their core essence; "Summarizing lecture slides before class" evolved into "summarizing lecture content." These paraphrased statements were then grouped into thematic clusters following Mayring’s (2021) approach; the first author conducted the initial clustering, and the second author independently reviewed and verified the categories: Content Summarization, including tasks like summarizing readings and upcoming topics; Definitions and Key Concepts, capturing efforts like providing definitions and deconstructing concepts; Learning Objectives and Preparation, where objectives and preparation strategies were outlined; Reviewing Previous Material; and Question Preparation.

To reduce the number of themes, we simplified and structured each thematic cluster, thoughtfully merging closely related clusters. For instance, Content Summarization and Definitions and Key Concepts were united into the broader category of Content Understanding. Similarly, we integrated Learning Objectives and Preparation, Reviewing Previous Material, and Question Preparation into the category of Learning Preparation.

Finally, in our categorization stage, we delineated two principal categories: (1) Content Understanding, encompassing the summarization of readings and lecture materials and the explanation of key terms and concepts; and (2) Learning Preparation, which includes the identification of learning objectives, support for class and content organization, reviewing prior content, formulating questions, and familiarizing with upcoming topics.

To validate our two primary categories, we carefully reviewed and reassigned each original statement into one of these final categories. For example, statements such as "summarizing unread texts" or "breaking down concepts" were thoughtfully placed under Content Understanding, while those like "assisting with class preparation" or "helping prepare questions" were classified under Learning Preparation. In the concluding analysis and thematic interpretation, our category framework revealed much about the data: Content Understanding mirrored students' desire for concise summaries and clear elucidations of the materials, while Learning Preparation focused on organizational assistance, goal setting, and cognitive readiness before lectures. Throughout the initial phases of our analysis, Mayring’s (2021) method of content analysis guided us and provided a systematic path through incorporating and considering all textual data from all four questions.

Through our qualitative content analysis, we discovered something interesting: students seem to view GenAI as an adaptable learning companion that supports them at every stage of the lecture cycle before, during, and after class. This insight, quite excitingly, linked seamlessly with our interpretation of the SRL model. Greene and Azevedo (2007), along with Panadero (2017), have extensively discussed these phases and subprocesses within self-regulated learning, which helped us draw parallels between our thematic patterns and their scholarly work. Zimmerman’s (2000) model of SRL provides a valuable foundation that underscores this alignment. In the sections that follow, we delve deeper into how we interpreted how the themes correspond to Zimmerman’s model of SRL (Figure 1).

Before our lectures, many students found themselves seeking help to better organize and orient their learning activities — a collection of actions providing a hallmark of the Forethought phase in SRL. The most frequent scenario they described involved summarizing lecture content and the preparatory materials, like slides and readings. This kind of support is seen as pivotal for task analysis, aiding students in assessing scope, relevance, and pinpointing the conceptual focus during this foundational phase. Furthermore, students voiced a clear need for GenAI by identifying and explaining complex terms and concepts, aligning with both the task analysis stage and the performance phase’s self-control subprocess (Panadero, 2017). They wanted content reformulated in a way that feels cognitively approachable. Additionally, students pointed out the crucial role of GenAI in defining learning objectives and creating strategies for preparation. Engaging in reviewing past materials, drafting potential questions, and diving into new topics showcases strategic planning and self-judgment, reflecting students' keen awareness of the cyclic, metacognitive journey of learning preparation.

During our lectures, we framed GenAI as a real-time cognitive aid aimed at enhancing learning performance. Students expressed hopes for support in three main areas: (1) transcription and notetaking, (2) immediate clarification and questioning, and (3) ongoing engagement with instructional content. These anticipations align with the performance phase of SRL, particularly the aspects of self-control, like effective notetaking and time management, self-observation, such as recognizing real-time confusion, and task strategies, including problem-solving and maintaining focus. For instance, students saw automated transcription and summarization as means to reduce cognitive load, allowing them to focus more on comprehension and elaboration rather than on manually documenting information. The capacity to ask questions and receive instant clarification from GenAI tools appeared integral to help-seeking and self-observation processes, especially when instructors were not immediately available. Moreover, students described GenAI as a scaffold for active participation and comprehension through its adaptive ability to track and elucidate lecture content dynamically.

Figure 1

Zimmerman’s Model of Self-Regulated Learning

Note. Zimmermann (2000).

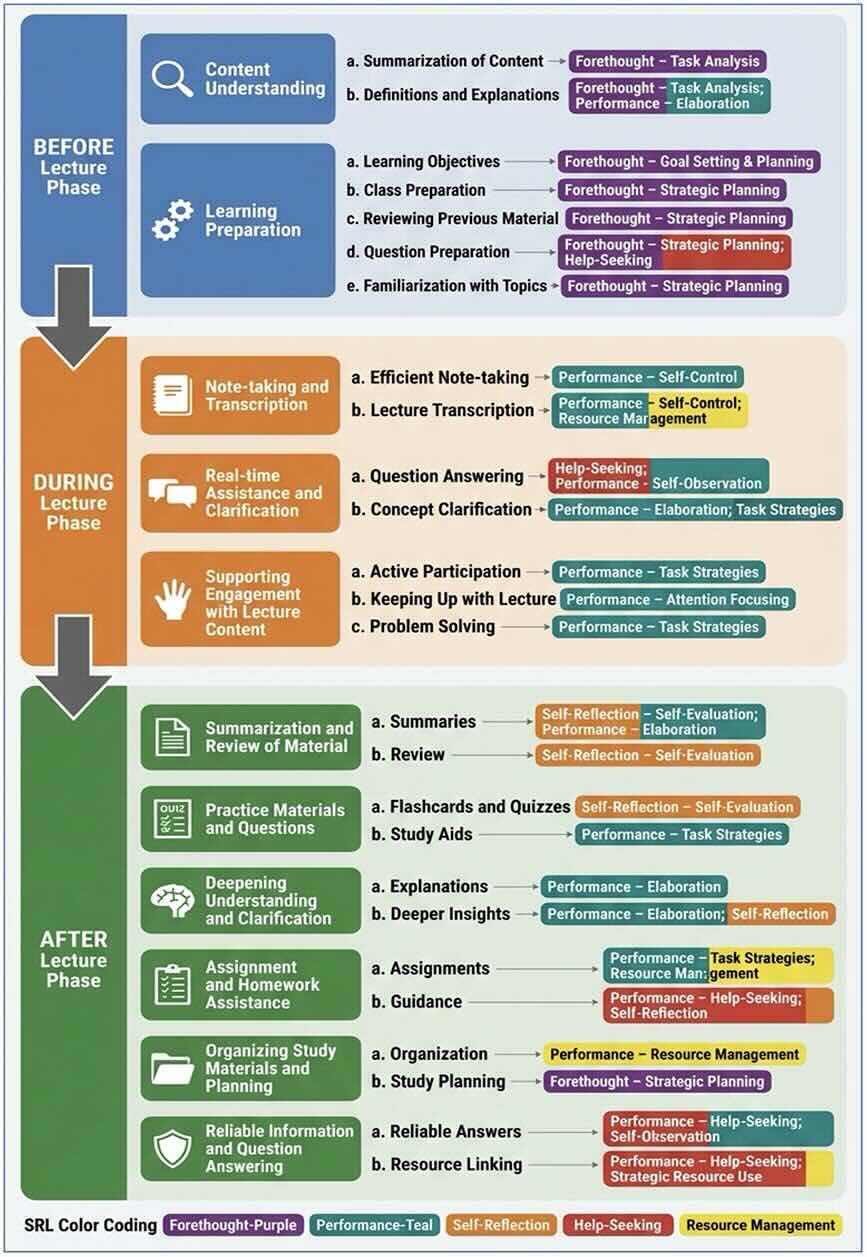

After attending lectures, many students increasingly turn to GenAI to consolidate their knowledge, review materials, and apply new concepts, a trend that aligns with the self-reflection and performance phases of SRL. Students commonly employ GenAI for self-evaluation by generating summaries, practice quizzes, and flashcards which are tools crafted to both assess and enhance their understanding. Moreover, they appreciate GenAI's capability to explain complex concepts, offer detailed explanations, and provide tailored feedback, directly supporting their elaboration and self-reaction processes during learning. An emerging critical application of GenAI within academic settings is its use for assignments and homework, with students frequently seeking assistance in understanding tasks, completing them, and managing their study plans. This behaviour ties into resource management, task strategy execution, and help-seeking, suggesting GenAI’s dual role as a mentor and study manager. Additionally, students rely on GenAI for organizing notes, scheduling study sessions, and linking various resources, which corresponds with strategic planning and resource management. We have synthesized these findings and mapped the expectations and SRL processes throughout the lecture timeline in Table 1. In our subsequent analysis phase, we delve deeper, using SRL theory as a lens for the deductive interpretation of themes identified during the inductive phase.

In response to the fourth question regarding the use of GenAI in education, our exploration reveals insightful perspectives from students. Although there is palpable enthusiasm for integrating GenAI into academic routines, students demonstrate a crucial awareness of its inherent risks and limitations. Many concerns align closely with vulnerabilities identified in the SRL framework.

Firstly, students perceive overreliance on GenAI as potentially detrimental to developing self-control and sustaining motivation. They worry that consistent AI support might dampen independent learning, impede critical thinking, and reduce engagement with tough material. Such observations echo findings in the existing SRL literature.

Secondly, concerns about content accuracy and contextual appropriateness surface prominently. Students express that unreliable AI outputs could jeopardize their self-evaluation processes, offering misleading benchmarks for academic performance. Ethical considerations were another significant theme. Many students voice apprehensions about crossing academic integrity boundaries such as plagiarism or unauthorized assistance in the absence of explicit institutional guidelines. These ethical concerns could disrupt strategic help-seeking behaviours, a core aspect of SRL. Additional points of concern include apprehensions regarding data privacy, algorithmic bias, and a lack of transparency in AI decision-making processes, which were topics repeatedly emphasized in student feedback.

Ultimately, these reflections highlight how students’ concerns relate to the potential impact of GenAI on self-regulated learning. Their critical awareness of overreliance, inaccuracies, and ethical dilemmas underscores GenAI’s dual role: both a tool for intellectual capacity building and a potential challenge in educational contexts. Students' perspectives reflect their nuanced understanding of GenAI within the educational sphere, paralleling the institutional portrayals of GenAI as a productive tool.

Figure 2

Mapping Student Use of GenAI Across Lecture Phases Using Self-Regulated Learning Processes

Note. Figure created with Nano Banana AI.

Taken together, the mapping of themes with phases of SRL suggests that students conceptualize GenAI as more than just a production tool, contrary to the framing in many institutional discourses, and regard it as a mechanism for intellectual capacity building. Student expectations for GenAI reflect an integrated understanding of cognitive, metacognitive, and motivational needs across all phases of the SRL process. However, this vision is tempered by an acute awareness of GenAI’s potential to disrupt SRL processes. The risk of reduced learner autonomy (self-control), impaired evaluative judgment (self-evaluation), and ethical ambiguities (strategic use) suggests a need for pedagogically guided integration of GenAI in higher education settings. These tensions between enhancement and erosion of SRL highlight the importance of designing GenAI systems that support rather than supplant students’ self-regulatory capabilities.

This study explored how undergraduate students use GenAI tools to support learning before, during, and after lectures, and documented their concerns about GenAI in higher education. Through qualitative content analysis, we identified that students envision distinct, phase-specific roles for GenAI: preparation (e.g., summarizing materials), real-time support (e.g., note-taking, clarifications), and post-lecture consolidation (e.g., review aids, assignment assistance). These expectations aligned closely with Zimmerman’s (2000) SRL, highlighting subprocesses such as task analysis, strategic planning, self-control, self-evaluation, and help-seeking. However, students also expressed critical concerns, emphasizing risks such as overreliance on GenAI weakening self-control and motivation, inaccuracies undermining self-evaluation, and ethical issues related to academic integrity, data privacy, and responsible use.

Our study makes a unique contribution to ongoing discourse by explicitly mapping undergraduate students’ use of GenAI onto Zimmerman’s SRL framework, systematically aligning student expectations with SRL subprocesses across instructional phases. Prior research has broadly discussed GenAI usage patterns and ethical considerations (e.g., Ally & Mishra, 2025; Shaw et al., 2023), but the structured alignment presented here extends existing insights into how students actively self-regulate their learning with GenAI tools through metacognitive and motivational engagement. This alignment resonates with recent empirical findings, underscoring the synergistic interaction between learner characteristics and GenAI affordances to enhance SRL capacities, particularly through personalized feedback, positive attitudes, and strategic engagement (Wu & Chiu, 2025). Furthermore, our results align with Pan et al. (2025), who found that GenAI-enabled interactive personalized support significantly boosted university English as a foreign language learners’ self-regulated strategy use and reading engagement, highlighting GenAI’s role in fostering deeper cognitive engagement and strategic reading processes. Additionally, our findings reinforce the argument made by Xu et al. (2025) that GenAI, while supporting learning tasks effectively, also presents risks such as decreased self-regulatory effectiveness if not coupled with adequate metacognitive scaffolding.

Moreover, our findings reveal a critical conceptual shift: while institutions often frame GenAI primarily as a production-focused tool, emphasizing outputs and raising concerns about academic integrity and cheating, students perceive these technologies fundamentally differently, viewing them as tools for intellectual capacity building. Echoing Chu’s (2025) conceptualization of GenAI as a tool for thinking, students describe GenAI as a collaborative partner that supports intellectual labour, facilitates deeper understanding, and fosters critical engagement. This student-oriented view aligns closely with findings from Fayaza and Senthilrajah (2025), who demonstrated that interaction with GenAI aids students in grasping complex concepts, thereby improving intellectual capacity and information retention, though they caution that improper use could negatively affect skills development. Extending this perspective, Qu et al.’s (2025) meta-analysis revealed that GenAI significantly enhances lower-order cognitive outcomes, such as understanding and application of concepts, while also influencing higher-order cognitive skills, indicating a direct impact on students’ intellectual growth. Daniel et al. (2025) further substantiate GenAI’s contribution to academic skills development, framing it explicitly as a tool for intellectual enhancement. Likewise, Yusuf et al. (2025) acknowledge GenAI’s capability to manage complex tasks, hinting at its potential to engage and develop sophisticated intellectual abilities. Collectively, these findings underscore the importance of reframing GenAI integration in education from a purely production-centric perspective to one that emphasizes cognitive support, intellectual agency, and deeper learning.

Our methodological approach provided insights while presenting several important limitations. Using a qualitative survey methodology enabled us to efficiently capture diverse student perspectives across various disciplines, enhancing the generalizability of our findings beyond disciplines typically overrepresented in qualitative research, such as engineering or computer science. Furthermore, employing face-to-face recruitment strategies combined with QR-coded flyers improved response rates compared to email-based recruitment alone, underscoring the importance of direct student engagement. However, the reliance on open-ended questions within our survey design restricted the depth and context-specific detail of responses, limiting our ability to probe or clarify student answers. As a result, we likely missed nuanced explanations of how students use GenAI tools differently across learning contexts or for the same tasks (e.g., summarization) in varied ways. Additionally, the absence of demographic analysis (e.g., gender, year of study, previous GenAI experience, learning modality) further constrains our understanding of how different student populations perceive or engage with GenAI. Future research could address these limitations through complementary qualitative methods, such as interviews, focus groups, or diary studies, allowing for deeper, context-rich exploration of students' real-time interactions, evolving perceptions, and individual differences regarding GenAI tools across diverse learning scenarios.

Educators should intentionally integrate GenAI tools into course designs that mirror the phases of SRL. Before lectures, instructors can assign tasks that use GenAI for summarizing readings, defining key concepts, and setting learning goals to foster task analysis and strategic planning. During class, GenAI can support real-time notetaking, on-the-fly clarification, and prompts for reflection to strengthen self-control and help-seeking behaviours. After lectures, structured activities such as GenAI-generated practice quizzes, flashcards, and guided review prompts can reinforce self-evaluation and elaboration. To address student concerns, instructors should embed explicit discussions and reflective exercises about overreliance, accuracy, and academic integrity. For example, brief in-class exercises comparing AI-generated and human-created summaries can sharpen evaluative judgment, while ethics case studies can enhance awareness of responsible use. At the policy level, institutions should shift from restrictive bans toward comprehensive frameworks that emphasize digital literacy, capacity-building, and ethical guidance. This includes offering workshops on effective GenAI use, developing clear guidelines that balance innovation and integrity, and providing ongoing support for faculty to co-design assignments that leverage GenAI as a cognitive partner. By aligning teaching practices and policies with students’ nuanced understanding of GenAI as a tool for intellectual capacity, higher education can foster responsible, self-regulated learning.

The findings highlight the importance of conceptualizing GenAI not solely as a single-purpose technology but as a dynamic support system that can be tailored to each phase of the learning cycle. Students’ reported use demonstrates that AI can augment—and not supplant—their active engagement with course material. In practice, instructors should embed GenAI tools deliberately into their course design, providing clear guidance on ethical and effective usage before, during, and after lectures. Such integration can cultivate critical digital literacy and address student concerns about overreliance, misinformation, and academic integrity. Future research would benefit from more granular qualitative approaches such as in-depth interviews or diary studies to observe students’ real-time interactions with GenAI across varied learning contexts. It should also include the learning modality and the instructor’s role, as well as specifying learning outcomes, to make the impact more visible and comparable with other research. Comparative investigations across different institutions, disciplines, or cultural settings could reveal broader patterns in GenAI adoption. Finally, the ethical issues raised by students including data privacy and intellectual autonomy demand focused attention from both researchers and developers to ensure GenAI’s responsible and supportive role in higher education.

ChatGPT (OpenAI) was used to enhance the clarity and conciseness of the language in this article, employed solely for language refinement, and did not contribute to the generation of original content or interpretation of findings. Additionally, we used Nano Banana AI for creating the Infographic in Figure 2.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Ann-Kathrin Grenz. Email: ann-kathrin.grenz@fit.fraunhofer.de

Ally, M., & Mishra, S. (2025). Policies for artificial intelligence in higher education: A call for action. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 50(3). https://doi.org/10.21432/cjlt28869

Ammari, T., Chen, M., Zaman, S. M. M., & Garimella, K. (2025). How students (really) use ChatGPT: Uncovering experiences among undergraduate students [Preprint]. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.24126

Aure, P., & Cuenca, O. (2024). Fostering social-emotional learning through human-centered use of generative AI in business research education: An insider case study. Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning, 17(2), 168-181. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIT-03-2024-0076

Bittle, K., & El -Gayar, O. (2025). Generative AI and academic integrity in higher education: A systematic review and research agenda. Information, 16(4), Article 296. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16040296

Chambers, L., & Owen, W. J. (2024). The efficacy of GenAI tools in postsecondary education. Brock Education: A Journal of Educational Research and Practice, 33(3), 57-74. https://doi.org/10.26522/brocked.v33i3.1178

Chiu, T. K. (2025). Instructional designs for AI interdisciplinary learning. In Empowering K-12 education with AI. Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003498377

Chiu, T. K. F. (2024). A classification tool to foster self-regulated learning with generative artificial intelligence by applying self-determination theory: A case of ChatGPT. Educational Technology Research and Development, 72, 2401-2416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-024-10366-w

Daniel, K., Msambwa, M. M., & Wen, Z. (2025). Can generative AI revolutionise academic skills development in higher education? A systematic literature review. European Journal of Education, 60(1), e70036. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.70036

Eacersall, D., Pretorius, L., Smirnov, I., Spray, E., Illingworth, S., Chugh, R., Strydom, S., Stratton-Maher, D., Simmons, J., Jenning, I., Roux, R., Kamrowski, R., Downie, A., Thong, C. L., & Howell, K. A. (2024). Navigating ethical challenges in generative AI-enhanced research: The ETHICAL framework for responsible generative AI use (arXiv Preprint No. 2501.09021). arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.09021

Fayaza, M. F., Senthilrajah, T., Wijesinghe, U., & Ahangama, S. (2025, February). Role of GenAI in student knowledge enhancement: Learner perception. In 2025 5th International Conference on Advanced Research in Computing (ICARC) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

Golding, J. M., Lippert, A., Neuschatz, J. S., Salomon, I., & Burke, K. (2024). Generative AI and college students: Use and perceptions. Teaching of Psychology, 52(3), 369-380. https://doi.org/10.1177/00986283241280350

Greene, J. A., & Azevedo, R. (2007). A theoretical review of Winne and Hadwin’s model of self-regulated learning: New perspectives and directions. Review of Educational Research, 77(3), 334-372. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430303953

Guillén-Yparrea, N., & Hernández-Rodríguez, F. (2024). Unveiling generative AI in higher education: Insights from engineering students and professors. In 2024 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON) (pp. 1-5). https://doi.org/10.1109/EDUCON60312.2024.10578876

Hamerman, E. J., Aggarwal, A., & Martins, C. M. (2025). An investigation of generative AI in the classroom and its implications for university policy. Quality Assurance in Education, 33(2), 253-266. https://doi.org/10.1108/QAE-08-2024-0149

Holechek, S., & Sreenivas, V. (2024). Abstract 1557: Generative AI in undergraduate academia: Enhancing learning experiences and navigating ethical terrains. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 300(3), 105921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbc.2024.105921

Huang, D., Huang, Y., & Cummings, J. J. (2024). Exploring the integration and utilisation of generative AI in formative e-assessments: A case study in higher education. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 40(4), 1-120. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.9467

Johnson, D. M., Doss, W., & Estepp, C. M. (2024). Agriculture students’ use of generative artificial intelligence for microcontroller programming. Natural Sciences Education, 53, e20155. https://doi.org/10.1002/nse2.20155

Johnston, H., Wells, R. F., Shanks, E. M., Boey, T., & Parsons, B. N. (2024). Student perspectives on the use of generative artificial intelligence technologies in higher education. International Journal for Educational Integrity 20(2). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-024-00149-4

Johri, A., Hingle, A., & Schleiss, J. (2024). Misconceptions, pragmatism, and value tensions: Evaluating students' understanding and perception of generative AI for education. In 2024 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE) (pp. 1-9). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/FIE61694.2024.10893017

Mayring, P. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: Theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. Klagenfurt. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173

Mayring, P. (2021). Qualitative content analysis : A step-by-step guide. Sage Publications.

Pan, M., Lai, C., & Guo, K. (2025). Effects of GenAI-empowered interactive support on university EFL students' self-regulated strategy use and engagement in reading. The Internet and Higher Education, 65, 100991. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2024.100991

Panadero, E. (2017). A review of self-regulated learning: Six models and four directions for research. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 422. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00422

Qu, X., Sherwood, J., Liu, P., & Aleisa, N. (2025, April). Generative AI tools in higher education: Ameta-analysis of cognitive impact. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1-9). https://doi.org/10.1145/3706599.3719841

Qu, Y., Tan, M. X. Y., & Wang, J. (2024). Disciplinary differences in undergraduate students’ engagement with generative artificial intelligence. Smart Learning Environments, 11, Article 51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-024-00341-6

Razmerita, L. (2024). Human-AI collaboration: A student-centered perspective of generative AI use in higher education. In Proceedings of the European Conference on e-Learning, 320-329. https://doi.org/10.34190/ecel.23.1.3008

Sajja, R., Sermet, Y., Fodale, B., & Demir, I. (2025). Evaluating AI-powered learning assistants in engineering higher education: Student engagement, ethical challenges, and policy implications [Preprint]. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.05699

Shaw, C., Yuan, L., Brennan, D., Martin, S., Janson, N., Fox, K., & Bryant, G. (2023, October 23). Generative AI in higher education. Tyton Partners. https://tytonpartners.com/time-for-class-2023/GenAI-Update

Soliman, M., Ali, R. A., Khalid, J., Mahmud, I., & Ali, W. B. (2025). Modelling continuous intention to use generative artificial intelligence as an educational tool among university students: Findings from PLS SEM and ANN. Journal of Computers in Education, 12, 897-928. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40692-024-00333-y

Sun, L., & Zhou, L. (2024). Does generative artificial intelligence improve the academic achievement of college students? A Meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 62(7), 1676-1713. https://doi.org/10.1177/07356331241277937

Tang, M., Dong, J., & Cheng, S. (2025, June). Assessing university students’ acceptance of generative artificial intelligence based on the UTAUT Model. In Proceedings of the 2025 4th International Conference on Educational Innovation and Multimedia Technology (EIMT 2025) (pp. 285-291). Atlantis Press. https://doi.org/10.2991/978-94-6463-750-2_27

Wang, C., Wang, H., Li, Y., Dai, J., Gu, X., & Yu, T. (2024). Factors influencing university students’ behavioral intention to use generative artificial intelligence: Integrating the theory of planned behavior and AI literacy. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 41(11), 6649-6671. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2024.2383033

Wang, K. D., Wu, Z., Tufts II, L. N., Wieman, C., Salehi, S., & Haber, N. (2024). Scaffold or crutch? Examining college students’ use and views of generative AI tools for STEM education [Preprint]. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.02653

Wu, X.-Y., & Chiu, T. K. F. (2025). Integrating learner characteristics and generative AI affordances to enhance self regulated learning: A configurational analysis. Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research, 14, Article 10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44322-025-00028-x

Xu, X., Qiao, L., Cheng, N., Liu, H., & Zhao, W. (2025). Enhancing self‐regulated learning and learning experience in generative AI environments: The critical role of metacognitive support. British Journal of Educational Technology, 56(5), 1842-1863. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13599

Yang, X., Liu, X., & Gao, Y. (2025). The impact of Generative AI on students’ learning: A study of learning satisfaction, self-efficacy and learning outcomes. Educational Technology Research and Development. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-025-10540-8

Yusuf, A., Pervin, N., Román-González, M., & Noor, N. M. (2024). Generative AI in education and research: A systematic mapping review. Review of Education, 12, e3489. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3489

Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Attaining self-regulation: A social cognitive perspective. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of Self-Regulation (pp. 13-39). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012109890-2/50031-7

Ann-Kathrin Grenz is Researcher at Fraunhofer FIT in Germany, specializing in learning and generative AI. With a background in psychology and computer science, she explores how humans interact with intelligent systems and how AI can enhance education. Her work bridges technical innovation with evidence-based understanding of human behaviour. Email: Ann-kathrin.grenz@fit.fraunhofer.de ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9849-4923

Soroush Sabbaghan is Associate Professor at the University of Calgary and the inaugural Generative AI Educational Leader in Residence at the Taylor Institute for Teaching and Learning in Canada. His work focuses on the intersection of educational technology, teacher development, and equity, supporting inclusive and evidence-informed teaching practices for K-12 and higher education.

Email: ssabbagh@ucalgary.ca ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2236-7693

Michele Jacobsen is Professor of Learning Sciences at the University of Calgary in Alberta, Canada. Her research examines technology-enhanced learning, graduate supervision, and student experience in higher education. She co-leads the National Community of Practice on Supervision and publishes widely on online learning, graduate education, and the scholarship of teaching and learning. Email: dmjacobs@ucalgary.ca ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0639-7606